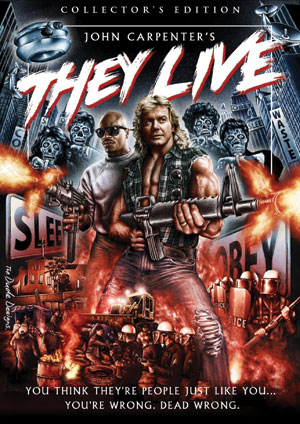

“I have come here to chew bubble gum and kick ass. And I’m all out of bubble gum.” It’s an iconic line from John Carpenter’s 1988 horror satire They Live, in which an unemployed Los Angeles construction worker called Nada stumbles upon a pair of sunglasses that reveal the world for what it really is.

Superficially, Reagan-era America looked like a free-market utopia where anyone could succeed with a little effort. But seen through those sunglasses, modern US society was a fractured jungle where a tiny minority of aliens (representing the plutocracy) imposed social order by means of subliminal mind control.

Street hoardings, seen through the sunglasses, suddenly barked commands like “Stay asleep”, “Submit to authority”, “No imagination”. Dollar bills had a special message: “This is your god.”

The more I watch the evolution of the slow-moving debt crisis as it seeps into every aspect of financial life, the more I think of this film. There’s a fundamental unfairness at the roots of our modern markets. I’m not quite old enough to be a baby boomer, but that was the generation that, with hindsight, ate all the pies.

It’s the generation that enjoyed equity-market booms and property-market booms and is likely to be enjoying a comfortable retirement with a mix of state and private pensions. It’s also the generation that David Cameron is still courting assiduously ahead of the forthcoming general election.

Those benefits are coming at the expense of the young. I’m not young enough to be a Millennial, but the generation that came of age over the last decade or so is an unlucky one, for whom I have tremendous sympathy.

Property prices are through the roof. Higher education (any education) is getting prohibitively expensive. Everyone now faces a future of competing for work with the rest of the world – and that presumes there are jobs to be had when the Millennials graduate, if they or their parents can still pick up the tab for years of study.

A breakdown of trust

For our modern society to work, with maximum opportunity for all, there needs to be trust. The market analyst Dylan Grice has pointed out that we do not exchange with people we don’t trust. “You work for your employer because you trust them to pay you.

You get into an aeroplane because you trust the pilot not to crash. It’s trust that moves the economy.” Not to wax overly political, but we also pay taxes because we trust that the government will redirect our capital prudently and fairly.

This trust is impossible if we have money we can’t trust. In Grice’s words, “when you devalue money, you devalue trust”. I recently saw a photo of an angry mob on Twitter – which tends to specialise in angry mobs – with someone holding a poster: “Why pay taxes when they can just print money?” In the circumstances, it’s an entirely fair question.

This week I was sent a chart of interest rates going back, not just to the founding of the Bank of England in 1694, but over 3,000 years – across the Babylonian, Greek and Roman empires, reflecting the lowest interest rate on offer from multiple markets. Current interest rates aren’t just low in the context of a lifetime, they’re at all-time lows in the context of the entire history of trade.

Economic policymakers are cheerfully supporting unprecedented monetary stimulus, despite the inconvenient truth that there is precisely zero evidence that it works. There seems to be an increasing risk that, far from reflating near-term demand, their approaches of quantitative easing, Zirp and Nirp (zero and negative interest-rate policies respectively) are encouraging outright deflation.

Why is that? Ask yourself this: just how insultingly negative would deposit rates have to go before you took your money out of the bank and kept it under the mattress instead? At a certain point, there would be every reason to do so. Bank counterparty risk hasn’t disappeared and it’s evident to anybody who thinks about it that the financial system is still on life support. Why else would base rates still be where they are?

Panic early

History tells us that if you’re going to panic, then panic early, and beat the crowd to get your money out. So all this adds up to the most dangerous market conditions any of us have ever seen, unpopular though it may be to point to the nudity of the Emperor: investors like a cheery story, and they absolutely detest bears.

They Live was, in common with many of John Carpenter’s later films, a cult classic rather than a blockbuster. Maybe it’s worthy of rediscovery by a larger audience. But on the other hand, why pay to watch a broken society of ultra-affluent ‘haves’ and a growing underclass of ‘have-nots’ when one can experience the real thing for free?

• Tim Price is director of investment at PFP Wealth Management. He also writes The Price Report newsletter (see thepricereport.co.uk).

Category: Market updates