Geopolitical risk and uncertainty in 2018 for UK investors

British investors will have to cope with geopolitical tensions and the influence of international relations on the share market in 2018. But can political risk analysis improve your portfolio results? What geopolitical forces are most likely to have a negative (or positive) impact on your returns? And how can you best cope with geopolitical uncertainty while remaining focused on your long term goals?

Before you can address investment questions, it’s important to understand what geopolitics actually is.

What is geopolitics?

In a nutshell, geopolitics is based on the idea that the great economic and military powers of the world are determined by geography. Access to waterways, arable farmland, rich mineral deposits, and location of key trade routes are all geopolitical forces that make a nation more or less powerful on the stage of world history.

The first man to popularise the field of political risk analysis and geopolitics in international relations was Sir Halford Mackinder. Mackinder was born in 1861, studied and taught geography, and would go on to become the Director of the London School of Economics. He’s widely considered to be the father of geopolitics and ‘geostrategy.’

Mackinder’s theory: ‘The World Island’

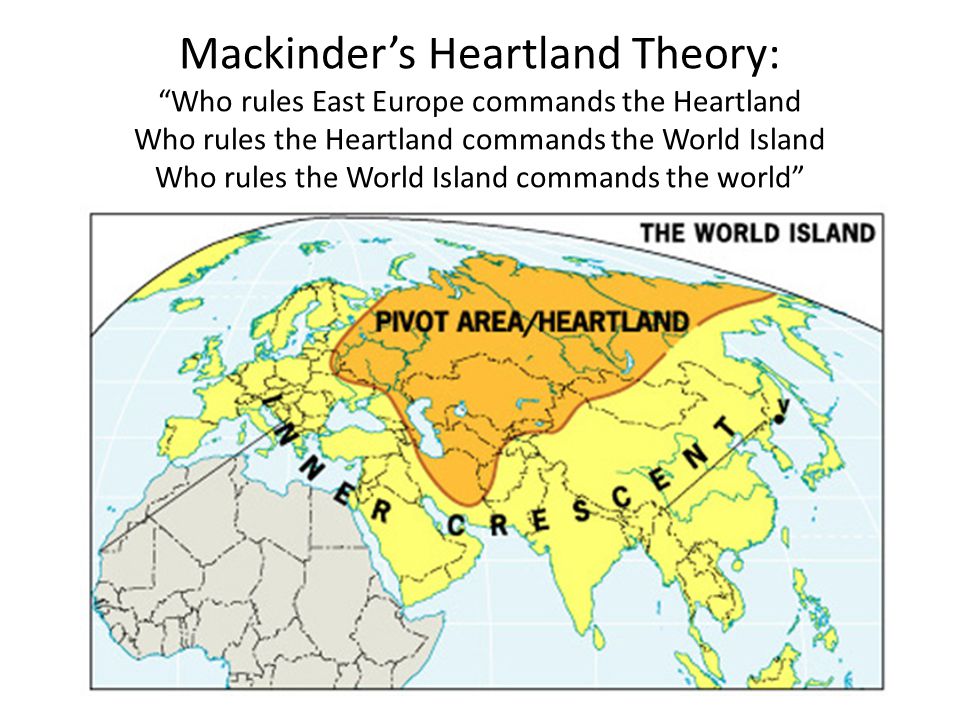

Mackinder’s grand theory can be summed up in what he called ‘The World Island.’ He argued that the world’s largest landmass ought to naturally be the world’s most powerful region. He then argued that it ought to be the goal of British (and later American) foreign policy to disrupt or contain the natural power bloc residing between Moscow, Beijing, and Tehran.

His analysis of geopolitical forces encouraged British foreign policy makers to disrupt the concentration of power by other countries in ‘the heartland,’ or Central Asia, which Mackinder believed would be the ‘pivot’ of global power.

This theory helps explain the history of British and American intervention (and geopolitical tensions) in places like Persia/Iran, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. A visual representation of the theory can be found below.

Source: George Gonzalez

Source: George Gonzalez

Jakub J Grygiel’s Great Powers and Geopolitical Change is an in-depth study of the ‘grand strategies’ of some of the world’s most powerful nations of the past thousand years. Among other things, it covers the rise and fall of the Venetian Republic and Ottoman Empire. It explains how places such as Britain, Spain and Portugal managed to punch above their weight and become ‘first rate’ powers.

Key trade routes

The book concludes the economic and geopolitical power is almost entirely dictated by the emergence of key trade routes. How does that work? Imagine a road running from the heart of Beijing on the east coast of China, all the way across the Eurasian land mass, through Constantinople, across the Balkans, past Venice and up into modern day Germany. For the sake of ease, we’ll call this the ‘Beijing Berlin Axis’.

Roughly speaking, this route governed the balance of power in the world for thousands of years. It linked east and west. And the nations that controlled it – or key parts of it – were more often than not the world’s first rate geopolitical powers.

The Venetians and Ottomans both controlled and shaped this route for hundreds of years. They became extravagantly wealthy and powerful in the process. Places like Britain were far away from the axis of power. We were frozen out. Unimportant.

Britannia Rising

The geopolitical map of the world changed profoundly in the late 15th century. Atlantic states such as England, Spain and Portugal developed boats that could travel long distances in relatively short periods of time. Explorers such as Columbus and Vasco da Gama discovered new trade routes – sea lanes – to America, India, Southeast Asia and China.

These new routes fundamentally changed the balance of power of the world. The overland ‘Beijing Berlin Axis’ was no longer the quickest or easiest route from east to west. It was quicker to travel by sea.

The geopolitical reality shifted. The centre of world power moved towards the Atlantic. British national strategy took full advantage. It wasn’t long before Britain had become the world’s biggest, richest and most powerful Empire. That’s the importance of geopolitics and strategic planning.

Geopolitical risk and uncertainty in 2018

China’s ambitious plan to build a ‘New Silk Road’ from Shanghai all the way to the Atlantic proves that Mackinder’s theory of geopolitical power – revolving around key trade routes and access to natural resources – is just as relevant today as it was at the beginning of the 20th century. But what does it mean for investors?

Oil tensions across the world

Key commodity prices like oil and gold will be a measure of geopolitical tensions. They also serve as an early ‘trip wire’ for inflation. This is related to macroeconomic and monetary policy. OPEC nations like Saudi Arabia and Iran, and non-OPEC nations like Russia, are all keen for higher oil and energy prices to boost their national coffers. Lower oil prices may stoke domestic political tensions in those countries and, by extension, geopolitical tensions with America and Europe.

The geopolitical implications of Trump’s presidency

American foreign policy toward other countries under President Donald Trump is one of great risks/geopolitical questions marks for this year and the next four. Trump’s early moves have exacerbated geopolitical tensions with traditional allies. His policy of putting trade and jobs at the centre of American foreign policy – rather that oil and national security – threatens to upend decades of US foreign policy and create new geopolitical risks.

The geopolitics of Brexit and the EU

Neither Europe nor the UK will be free from their own geopolitical issues in 2018. The triggering of Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty and the Brexit process will begin to clarify the geopolitical costs and benefits of leaving the EU. A second Scottish referendum may result, increasing geopolitical uncertainty.

Meanwhile, Europe may be the single-biggest geopolitical risk of 2018. Debt problems in Greece persist. Italians are flirting with an ‘exit’ of the Euro. EU leaders insist any country that leaves the common currency must also leave the European Union. Elections in Italy, Russia and Poland may well determine if the world’s centre of economic gravity and geopolitical power shifts back to Mackinder’s ‘Heartland.’