A rather long note today. If you want to get right to The Two Thrones of the global economy, skip down to the next heading. If you want to meander down some rabbit holes with me first, just keep on reading

They say absence makes the heart grow fonder. But then they also say, “out of sight, out of mind.”

When this mess is all over with, which of the two will have been a more accurate description of how we’ve treated the lockdown?

Will we go back to our previous habits hell for leather, hitting the pubs and taking holidays abroad like there’s no tomorrow… or when the doors are unlocked and the pubs re-opened, shall we simply stay put, comfortable in our new habits? Will we behave like carrier pigeons free of the coop, or like the elephants that tire of resisting their chains in childhood and never try again as adults? The investors who get this right stand to make a fortune, for there are always fortunes to be made when people’s habits change: either to adopt something new (like using a smartphone), or to return to something old (when prohibition was ended).

But like many questions, the answer may not be nearly so simple as a binary one or the other. The more I think of how we shall return to “normality”, the more I realise how subjective that is, depending upon how old you are, and how long we stay in isolation for. Right now, I’m very keen to flee my urban island as soon as I can, hit the pubs and take a flight out of here. But I fear the virus less as I’m pretty young and have no respiratory problems so I’m much less likely to be heavily afflicted by it. Were I much older, I would likely feel more risk averse.

This is, funnily enough, a standard assumption baked into the investment industry. It is assumed that young folks have a high appetite for risky investments which wanes into caution as they get older.

Strategies around this belief are implemented in pension schemes, financial advice frameworks and more, though of course there are many exceptions – a former colleague of mine has a client who’s old enough to have watched Spitfires dogfight Messerschmitts over the Channel when he was a kid but still has an incredibly bold appetite for risk, in the speculative territory.

And then of course you can argue over what “investment risk” actually is. Gold for example, is classed as a risky asset by the mainstream financial industry due to how volatile it can be, but of course gold investors see it as anything but risky.

In the case of the WuFlu, the concept of risk is rather more clear – in the extremis, there is the risk of death. But I get the impression that many of us are “fear fatigued” and becoming lax with the whole “social distancing” discipline – if that’s the case, it makes the “pubs and holidays x10” scenario more likely.

I bought a bicycle soon after I moved to London three years ago, but had barely used it until now. For some exercise over the weekends, I took it out again, pumped up the tires and have been going for a ride every so often around town. Chelsea over the weekend was incredibly busy considering how still things have been recently. It was maybe 75% as busy as it normally would be on a Saturday. But maybe that just says a lot about Chelsea…

Black Gold and Greenbacks: The Two Thrones

When it comes to the two sayings at the beginning of this letter, I’m much more in the “absence makes my heart grow fonder” camp. When I was a kid, my parents were very keen on preventing me from playing video games, as they didn’t want me to waste my youth in front of a screen. But whenever I’d play games at a friend’s house, the dopamine hit it granted would linger, and I’d be able to think of little else afterwards.

After years of dreaming of playing video games to my heart’s content without relying on the generosity of others, by the time I was a teenager and had gained funding via my paper round, I could finally plough my childhood away before a screen just as I’d always wanted.

And there was one game in particular I knew I had to play. One kid in my class had liked it so much he’d presented it to the class for show ‘n’ tell when we were ten. It was called Prince of Persia: The Two Thrones.

This was the final instalment in a trilogy that became one of the largest franchises of the mid-2000s. It was developed by a company called Ubisoft ($UBI) and led, like many successful games like it, to a terrible Hollywood adaptation. (Ubisoft has since fallen from grace and is a great example of how allowing private equity firms to take a stake in a business leads to the ruining of its product while increasing its share price. But that’s another story.)

The Two Thrones sees the main character, known only as the Prince, return to his home of Babylon only to find it in the process of being sacked by an evil Vizier he believed was already dead.

As he tries to defeat the Vizier and retake the kingdom all on his own, he realises he has become corrupted by his mystical misadventures in the previous games. His selfishness and greed which kept him alive prior to his return, is now manifesting itself physically upon his body and is slowly consuming his noble self.

So begins a power struggle within himself as he struggles for control against “the dark prince” while trying to regain his kingdom, with both “princes” trying to use each other for their own benefit. This duality of the two princes is what led to the name of the title: The Two Thrones.

There is a similar duality at play within the global economy – two great forces at play which feed upon each other in a way that can be both positive and negative. Two “thrones” which the entire world is beholden to one way or another… and which have both become very volatile in the last few months.

The first is the dollar, the global reserve currency used in international trade and credit. The second – the “dark prince” – is oil, which is required to power the global economy but is in itself a reflection of the dollar, as it is primarily priced in dollars. It is also notorious for breeding corruption and conflict, and is plentiful in modern-day Persia – Iran.

Crucially however, the oil industry is the means by which much of the world gets its dollars, which it then needs to conduct international trade. Few institutions and corporations want to use emerging market currencies for long-term finance and trade deals due to their volatility and potential to be aggressively debased, and so they stick with the USD all over the world.

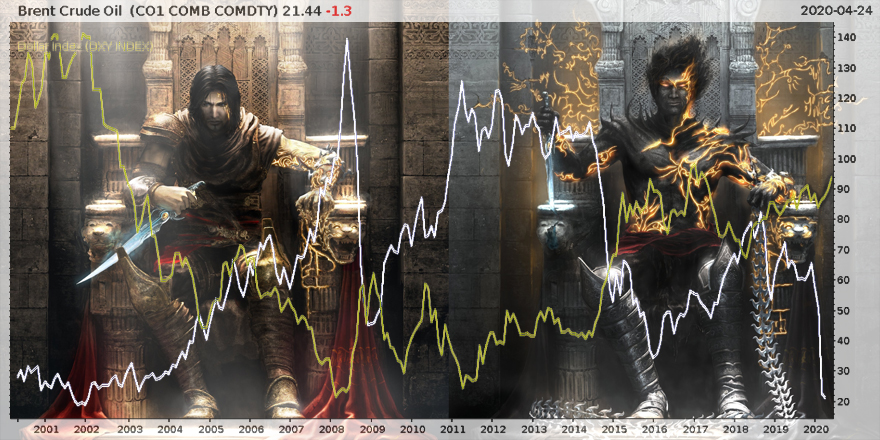

Take a look at the chart below – note how a high oil price coincides with a very weak dollar, as there are much more dollars being paid and circulated around the world via the oil producers. Conversely, note how a very low oil price has generally coincided with a stronger dollar, as the oil producers are earning less of them and so there are less to go around.

The Two Thrones: the price of Brent crude ($) in white, the dollar index (the value of a dollar measured against other major currencies) in gold

The Two Thrones: the price of Brent crude ($) in white, the dollar index (the value of a dollar measured against other major currencies) in gold

Source: me, on Twitter

This dynamic where a low oil price leads to a dollar shortage is a serious problem as vast quantities of dollar debt is owed outside of the US by corporations and foreign governments (again due to the dollars use as a trusted medium of exchange). The Federal Reserve cannot simply loan these guys the money, as the money came from a different channel before – the oil industry was the conduit. With a boatload of dollar debt and no printing press to cover, this puts these actors under a huge amount of pressure – and we’ve not seen this show itself yet.

Where this is particularly acute is Latin America, where nations like Mexico, Brazil, Ecuador, and of course Venezuela all rely on oil revenue, in dollars, to service debt and support their economies.

While the dollar index in the chart above may appear to rallying – the dollar gaining value against other major currencies – if you flip it around and look at the value of Latin American currencies in US dollars, you will see they’ve been going in only one direction in value, and are plumbing new all-time lows:

And while we’ve seen a recovery rally in equities in the US in recent days, the Latin American stocks are plumbing lows they’ve not seen since 2005 (when The Two Thrones was released, incidentally), breaking past lows seen in the depths of the financial crisis and the deflation fears of 2016:

It’s in the best interests of the world economy as it is that neither of the two thrones be “crowned” and gain a high price. While dollars make foreign debts much heavier, an extremely high oil price is a tax on pretty much all economic activity, and so chokes growth – either scenario leads to negative outcomes. But with oil hitting the basement, the former of those outcomes looks likely, as the flow of dollars is slowing to a trickle for the oil-producing countries that have borrowed plenty of them. Defaults beckon, and/or the printing of emerging market currencies to buy dollars, bidding up the dollar further.

Some market commentators think we’re well on the way out of this mess, just like all the folks growing bored of the social distancing routine. I think we’re a way off yet – the repercussions of what’s just happened to the world has yet to be fully appreciated, but they are in areas like LatAm. Just imagine timing the bottom in LatAm stocks perfectly after 2008… and still ending up with less money than you invested now…

Back tomorrow,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

For charts and other financial/geopolitical content, follow me on Twitter: @FederalExcess.

Category: Market updates