Oil kindles extraordinary emotions and hopes, since oil is above all a great temptation. It is the temptation of ease, wealth, strength, fortune, power.

– Shah of Shahs, Ryszard Kapuściński (1982)

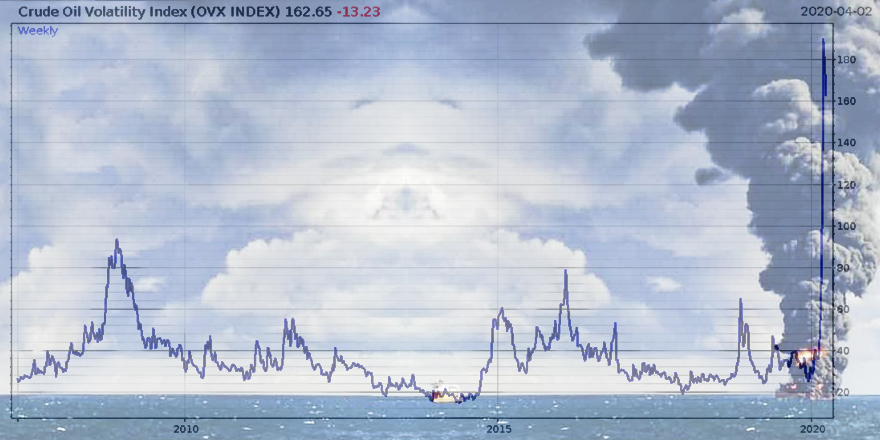

The chart speaks for itself.

When Donald Trump said he was a “very stable” genius, it seems he meant stable relative to the markets he comments on. He got the oil price to jump nearly 50% in a matter of hours with a couple of tweets saying Russia and Saudi were going to cut their production.

It’s an incredible feat: oil, the commodity which controls the world and inspires those deep emotions Kapuściński so eloquently described, has never rallied so hard and so fast in modern history. Three more days of that from The Donald and we’ll be looking at $100 a barrel once again.

The oil volatility index (OVX), which measures the cost of insuring against volatility in the oil price, mooned this year when the Russians and the Saudis turned on the oil taps and then went to bed. With yesterday’s action, it’s staying up there at unprecedented levels – the market has no confidence in calm returning to the oil market.

While we’re barely moving anywhere all cooped up indoors, the markets “out there” are moving ever faster. Pretty ironic, considering how low market volatility was when we were all milling around outside…

High oil: panacea or petrol bomb?

The question of whether a higher oil price right now is good or bad depends entirely upon where you’re standing.

An increase in the oil price will assist all those oil-producing nations in keeping their economies alive, and ease their shortages of dollars, helping them service their debts and in some cases help them maintain their exchange rate without having to devalue their currencies. It’ll also spare my dear Aberdeen from another brutal period of lay-offs and economic decline which occurred after the last oil collapse.

But Trump’s attempts are only focusing on the supply side: trying to decrease the amount of oil being brought to market. The answer of whether oil prices can be sustained is a question of demand: and that all depends on whether governments are going to let people go back to work. Hell, it depends on whether people are still going to have jobs to go back to when the government lets them go back to work.

Nearly a million Britons have signed on for welfare payments in the last fortnight alone. In the States, unemployment claims increased by 6.6 million just last week – that’s ten times higher than the worst week of the financial crisis.

When the world does return to work, a higher oil price may not actually be desirable, as a high oil price increases the basic cost of doing anything – not exactly what you need when there’s high unemployment.

However, the oil price is a long way from “high” at the moment, and I’m sceptical that The Donald will be able to keep it propped up with rhetoric. So is James Allen, our energy specialist – with any luck I’ll get him on the market broadcast to share his thoughts with you next week.

There’s something of a “halfway house” scenario for oil here where governments buy oil to fill their strategic petroleum reserves while oil is low, keeping the oil industry and oil-producing economies going during the dearth of demand. The Chinese Communist Party has just begun doing this, and considering China is the world’s largest consumer of oil (and commodities in general), this may be significant, a “marginal bid” keeping the market up.

This is something Akhil Patel has been writing about for years and while there’s plenty of doom and gloom out there right now, Akhil has recently written a very optimistic report on how asset prices will go from here. I’m writing this just as I’m about to ring him up for our daily market broadcast – you can listen to what he tells me here.

The petrodollar pump to save the day?

Jacking up the price of oil will help the oil-producing countries get their hands on dollars, and thus ease the dollar shortage if the high price can be maintained. For all the Federal Reserve’s actions to inject dollars into the financial system, ultimately it can’t inject them into the economies of oil-producing nations like a high oil price can.

We’ve been writing about the strength of the dollar and a global shortage of USDs for a few days now. All this talk of dollar strength reminded me of a conversation I had a couple of years ago now, with a fund manager called Brent Johnson who lives out in San Francisco.

Brent, while a firm believer in gold and a major disbeliever in the benefits of central banking and fiat currencies, believed that before gold had its time in the sun, that the dollar would rally so hard and become so strong that the price would collapse, as would all foreign currencies relative to it. The rest of the world would beg the US to devalue its currency and suffer significant stress from the global reserve asset becoming ever more expensive to attain.

He called it “the dollar milkshake theory”. Post crisis, all the money central banks had injected into financial markets around the world had turned them all into one big frothy milkshake. The US however, was the first central bank to start aggressively raising interest rates (aggressive relative to everybody else at least) and reducing the money supply it had injected.

Brent saw this as the Fed effectively poking a straw into the milkshake and sucking it out; attracting all of the sludge from everywhere else into the US with its higher rates. He thought that the US would actually start “stealing” all of the printed money from the rest of the world.

You can listen to the conversation we had here – it’s a little old, but Brent hasn’t changed his view, and he’s been looking increasingly correct in recent weeks.

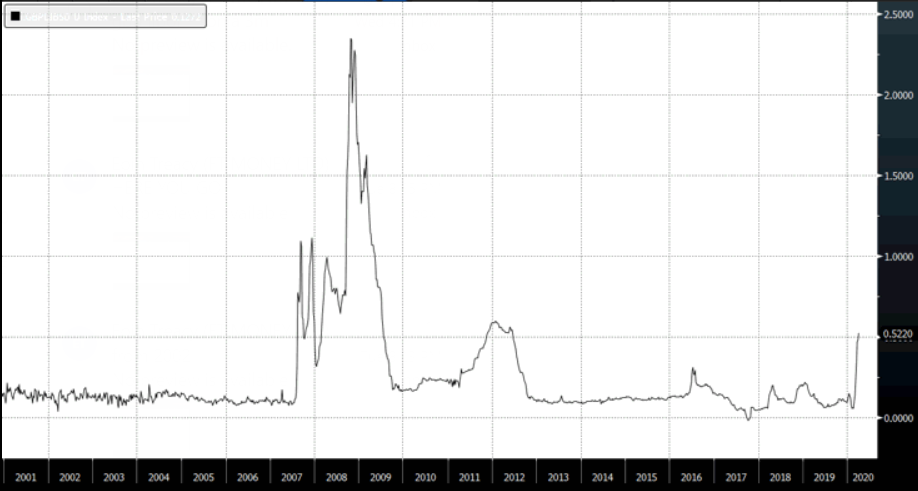

But enough talk of the US – let’s take a look at the UK banking system. I showed you the LIBOR-OIS spread a couple days ago which detailed the stress and mistrust developing there – I’ll show you the UK-focused version of it here.

This chart shows us the difference between the cost for banks to borrow cash for three months from each other, and the cost of borrowing overnight in the UK banking system (in sterling). To be more specific, it’s the difference between three-month GBP LIBOR and the SONIA, the Sterling Overnight Index Average.

SONIA is administered by the Bank of England (BoE), which also intervenes in the overnight market, so it’s effectively the difference between how low the BoE wants rates to be, and how low they actually are. When this blows up, it reveals that banks are not trusting each other:

It’s not looking as bad as the chart for the US banking system – the stress here is still lower than during the sovereign debt crisis – but this ordeal is far from over. I’ll be back with more next week.

Wishing you a good weekend – stay safe out there!

All the best,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

For charts and other financial/geopolitical content, follow me on Twitter: @FederalExcess.

Category: Market updates