I told you about the dearth of dollars in the global financial system yesterday. It’s a dynamic which threatens to cause chaos in the global financial system – especially in countries that don’t use dollars – and is already raising Cain in certain markets.

This global dollar shortage took a major turn after I’d published that note.

The Federal Reserve is now offering some 170 foreign central banks and “other international monetary authorities” the ability to pawn their US government debt with it in exchange for dollars. This goes above and beyond the “swap lines” which the Fed created with only a few other countries to help dollar shortages in the last financial crisis. And it says a lot of interesting things about what’s going on behind the scenes in the global banking system.

The US Treasury bond, the asset that would be pawned in this scenario, is supposed to be the most liquid asset in the world – the easiest asset to buy and sell in size without affecting its price or paying high commission fees. That the Fed is now standing in to short-circuit this market for major players suggests that this market – which much of the world relies upon – has become severely dysfunctional. Why can’t foreign central banks simply sell their US Treasuries, or pawn them to the private banking sector if they need dollars?

Or, instead, is the Fed afraid that foreigners are going to begin selling off their holdings of American assets – like US stocks and real estate – to get a hold of the dollars they need, and cause a further market crash?

Whatever the case, as it’s a pawnbroking arrangement that is being offered (known as “repo”, or “repurchase agreement”), this only creates further future demand for dollars. Provided of course that the foreign central banks that use this new facility don’t take the dollars and then don’t come back to pick the Treasury bonds.

Interestingly, this is what has been happening within the private banking system, where there has been a surge in banks pawning US Treasury bonds for dollars, and then just not buying them back again (what’s called a “repo failure”). We’re almost at $600 billion in such defaults so far this week, though we’ve yet to surpass the level of defaults reached in the middle of March 2017, which was near $700 billion.

You don’t hear all that much about this kind of thing. But in times like this, it pays to pry into the niches, the dark overlooked corners of the financial system to try and get a peek of what’s really going on.

Which leads me to a certain restaurant in Tampa, Florida, on 8210 Causeway Boulevard…

The Legend of Liborio

We in the UK herald Britannia as our national symbol; the French herald Marianne. The Swiss, a lady by the name of Helvetia, while the Americans who used to use a lady called Colombia as their symbol, use “Uncle Sam”.

In Cuba the equivalent of all these national symbols is a fella by the name of Don Liborio, who is commonly portrayed with a wide-brimmed straw hat, a white guayabera (a Cuban man’s summer shirt), and a machete. He apparently first appeared as a cartoon way back in 1900, and his image has been used to sell all manner of goods across the Americas, not least cigars.

Source: University of South Florida Library

Source: University of South Florida Library

I discovered Liborio quite by accident. It was a typo on my part – I was actually looking for a chart of a certain metric of stress in the banking system when I found myself looking at reviews for a Latin American restaurant in South Florida instead: Liborio’s, on Causeway Boulevard.

A typo on my part. I was looking for the LIBOR-OIS index. Now, this sounds pretty dull – I imagine most folks would be much more interested in a joint that sells Cuban food than the “spread” between the “London Interbank Offered Rate” and the “Overnight Index Swap”.

But LIBOR-OIS tells you how much the banks trust each other. And that’s a piece of information I’ll always lean in to eavesdrop on.

What LIBOR-OIS actually is, is the difference – known as the “spread” – between how much banks are charging each other for loans considered risky, compared to loans which are classed as “risk-free”. To be specific, this is the difference between the interest rate banks charge each other for three-month cash loans (no pawnbroking, straight-up cash)… and the interest rate they charge for overnight loans, which central banks (here and in the States at least) ensure are very low.

Central banks in many countries will target the overnight borrowing rate, and intervene in what’s called the “overnight market” to force that rate in the direction it wants (mostly down in recent decades).

To my eyes, the LIBOR-OIS spread is how much interest banks are charging each other above what the central banks wish they were. You see, in good times, the difference in interest rates in the short term should very low – the difference between an overnight loan and a three-month loan should be minimal.

If the difference between the overnight rate – that central banks control – and the three-month interest rate – which they don’t – starts blowing up, it means banks either don’t trust each other, or are finding it harder to issue loans. It also implies that central banks are losing control over the system itself.

That’s why former Fed chair Alan Greenspan looked to the LIBOR-OIS spread as a major warning system that something was going wrong in the banking system. And it’s why I was looking it up too – and found myself looking at a restaurant in Florida instead.

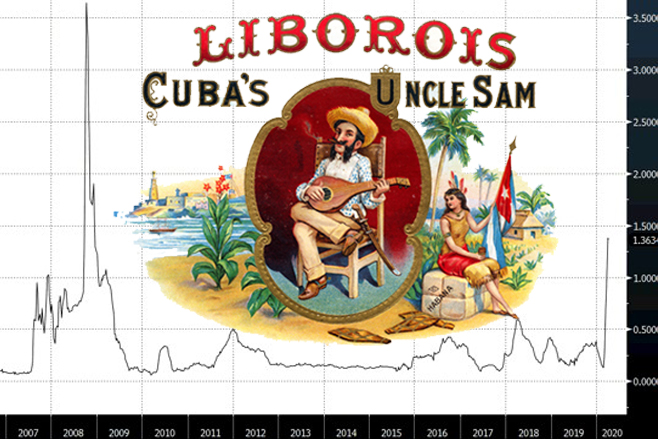

Anyhow, I’ve found the chart. And with a bit of Photoshop, I’ve brought Liborio along too, though I’ve changed his name slightly…

Source: me, on Twitter

Source: me, on Twitter

The LIBOR-OIS spread is blowing up in a way we haven’t seen since 2008. It’s not looking good, folks. Either banks don’t want to lend to each other, or they can’t.

That dollar shortage may well be the key, and why the Fed is trying to get dollars into foreign central banks so they can distribute them amongst their domestic banking system.

This is getting pretty nuts. Will chime in more on this tomorrow.

Killing time

All that stuff aside, I hope you’re getting on alright amidst the quarantine, and are getting some of this sunshine we’re lucky to have in London.

I rang up a relative of mine yesterday to check how he and his wife are getting on.

They live on a narrowboat, and so are already practicing a form of “social distancing” by default. I was interested to see if they’d been affected by the WuFlu in the same way it’s affecting city dwellers like me.

When he asked me how I was doing, I said I was feeling better now that the clocks had gone forward and there was more light in the day.

“Oh, was that what happened?” he said.

This fella hadn’t even noticed the clocks going forward. The time on his phone had automatically jumped an hour ahead – no notification required – and the evenings had just suddenly become dramatically longer for him. To hear that this was the explanation came as a pleasant surprise.

Something tells me that once all this is over, he’ll be just fine…

Until tomorrow,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates