Is it just me, or did the day the pubs shut feel like an incredibly long time ago for you too?

Seems like months since I’ve had a freshly poured pint in my hand. Let me tell you, when this lockdown is over I will be extending significant “financial support” to my local watering holes. It’ll be a one-man “People’s QE”, unleashing “animal spirits” at the bar.

I doubt I’ll be alone in my endeavours to inject an “economic stimulus package” into the nearest joint that sells Guinness though – I can’t be the only one feeling parched out there.

The issue is which of those pubs are actually going to be open once we make it out of captivity and back into the wild. Pub companies like Wetherspoon have achieved their aggressive expansion growth across our nation through an equally aggressive use of debt. With no income to keep the debt serviced while we’re in lockdown, the weight of that debt will grow and put ever more pressure on the company to close pubs the longer this lockdown lasts.

Debt. It’s a formidable drink of its own, and if you have too many it’ll just as easily leave you on the floor with no money and wondering how you got there. This is why Tim Price, our value investing expert over at The Price Report, doesn’t own any shares in ‘spoons (£JDW) in his fund, despite being a big fan of the chain. A good thing too as the shares just got glassed:

“I’m going to have to ask you to leave, sir” – investor assessing their holdings of £JDW

“I’m going to have to ask you to leave, sir” – investor assessing their holdings of £JDW

Source: me, on Twitter

You need a fair bit of Dutch courage to be buying any shares at the moment. I rang up Tim this morning to get his latest and see if he thought now was a good time to be getting into value companies – ones which haven’t gorged on debt in recent years. You can listen to it here.

Today’s note is not all about the booze industry and my close relationship with alcohol, however. We’re going back to something I was writing about in February, a pillar of the global financial system, inseparable from our country and its history… that has just begun emitting a lot of heat.

The financial system is controlled in paradi$e

I was thinking about pubs as it was on my fateful last visit to one, when pints were being handed out for free (the beer would go off during lockdown), that I noticed a relic of this system in the corner.

This last pub was a really old-school place, and it had a controversial antique on the wall: a map of the British Empire in its prime. The pink map itself, with all the imperial possessions – the perpetually offended would likely ring the police if you had it up in some London bar.

But on this map, tiny possessions like the Cayman Islands and Bermuda were underlined in pink, but dwarfed in importance by the vast land masses of Canada and India. These days, it’s those tiny islands that are all that is left of imperial power – though it’s not the kind of imperial power most people think of (navies, colonies, etc) and it’s never formally acknowledged.

In No empires for young men (25 February 2020) we explored how the post-WWII financial system was seeded in the remains of the British Empire, taking root in its obscure outposts. US banks were keen to set up offshore outposts in these areas, as this freed them from US regulations so they could loan out (and thus create) vast quantities of dollars with little backing them.

These offshore dollar factories are one of the reasons why the US ultimately went off the gold standard, but they are also the reason the US dollar is the global reserve currency today. The offshore banks were creating a currency trusted in trade and implicitly protected by the US military, a global means of exchange which for a while was as good as gold, and after it wasn’t, didn’t have a replacement. This system has continued to flourish in these imperial possessions where there is little regulation or taxation, and has become one of the largest capital markets in the world: the eurodollar market.

Dollars created offshore are known as eurodollars as US banks started their offshore operations in Europe to finance the rebuilding of the continent after World War II – it’s nothing to do with the € currency, and predates it by decades. “Euro” in this context simply means a bank deposit or physical currency outside the country where it is legal tender; “currency that’s on holiday”, you might say. Bring some pound notes to Italy? That’s eurosterling. Bring Japanese yen to Canada? That’s euroyen. And yes, bank deposits of euros, of physical euro notes outside of the eurozone, are indeed “euroeuro” (or should that be “euro-squared”?).

However, all of these other “eurocurrencies” are not nearly as common as eurodollars. Very few people, corporates, or foreign governments want to transact in sterling, yen, or euro when they could just use their own currency – or dollars. The market for eurodollar loans is huge, as is the system for holding eurodollar deposits.

But this is really just scratching the surface of how large and complex the eurodollar system has become. This unregulated offshore financial system has existed and been developing for well over half a century now and consists of vast interconnected bank liabilities, and dollar derivatives.

It is by far the world’s largest source of financing. Back in 1985 the eurodollar market was estimated at over $1.5 trillion, and it’s grown massively since then. Yet as it’s all unregulated and there is no central database, nobody knows exactly how huge it is. You can get glimpses of what’s going on inside it however, as we’ll come to.

A huge part of the development and growth of this system has occurred on British territory. And nobody in No.10 ever does anything about it, as it keeps the City as the world’s premier financial centre, keeps Washington on side as it reinforces the role of the dollar as the global reserve currency, and bolsters British prestige. I call it “The Imperial $ceptre”; financial power is one of Britain’s last great strengths – even if the currency isn’t our own.

I find the story of the eurodollar fascinating. The largest pool of capital in the world, and one of the most obscure and intriguing markets… is controlled in paradise. Oases of finance, unregulated and unrestrained, in the middle of the ocean under the Union Flag.

Of course, the administration of the market occurs in the City and other metropolitan financial centres – however, the banks do have outposts in these islands, and that’s where the balance sheets and offshore accounts are legally located.

The Panic in Paradise

In the last few notes we’ve been taking a look at how there appears to be a shortage of dollars in the financial system.

Now, you may wonder how there could be a shortage when banks in Bermuda can just magnify out vast quantities of money with little in reserve. But just because they’re unregulated, doesn’t mean they can counterfeit dollars – they still have to remain solvent even if they don’t play by “onshore” banking rules on reserve requirements.

Indeed, they’re more prone to risk as they have no government guarantees to bail them out like deposit insurance. That’s why interest rates in eurodollar banks are higher, as the market demands more reward for the risks inherent in storing and lending money offshore.

The vast amounts of credit created offshore, combined with the lack of reserves, makes for an incredibly levered and sensitive system. And there’s no central bank out there or treasury department to bail the offshore banks out, or at least not in the size and with the currency required. It may well be that the current dollar shortage actually began in the offshore market, which has since sucked in dollars from other markets and caused the dollar to rally against all the other currencies.

We can get an idea of just how much demand there is for dollars outside the US by taking a look at eurodollar futures. These are futures contracts traded onshore at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, to allow market participants to hedge or speculate on how strong the demand for offshore dollars will be. What they price is the market’s current expectation of dollar-funding conditions in the future – a higher price means dollars are harder to get.

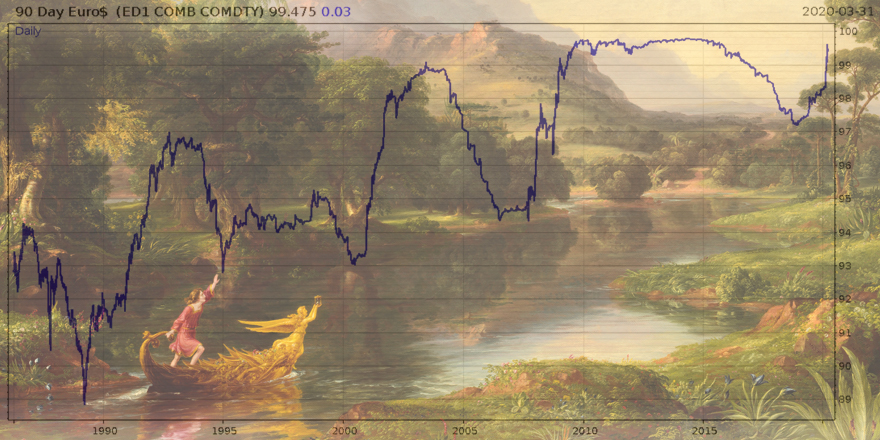

This is a chart of three-month eurodollar futures on a rolling basis since the 1980s. As you can see on the top right where we find ourselves today, well… they’re running low on dollars in paradise:

The price of three-month eurodollar futures on a rolling basis since 1985 – click to enlarge. A high price indicates high demand for dollars from outside the US from offshore banks and other financial entities. Note the sudden spike in the top right.

The price of three-month eurodollar futures on a rolling basis since 1985 – click to enlarge. A high price indicates high demand for dollars from outside the US from offshore banks and other financial entities. Note the sudden spike in the top right.

If you take a look back through the chart’s history, you can see that when the eurodollar future was heading downwards it was generally during the boom times: the late 90s, the mid 2000s, 2017. But every time things get hairy, the demand for dollars returns with a vengeance.

And if we view the eurodollar future as a measure of how “tight” dollar supply actually is out there, it appears to suggest that the offshore dollar supply is continually tightening through the decades.

Perhaps this is the offshore system gradually reaching a ceiling on the amount of leverage they can create? Or maybe it’s representative of slower global economic growth creating less dollars. Ultimately, I don’t know – but as I said in yesterday’s note, what happens to the dollar has global, rather than just American consequences.

If we see the dollar keep rallying as it has, it’s going to crush those with dollar debt, which not only creates economic pain (especially in emerging markets), but threatens the solvency of banks, and thus depositors. It will place an anvil on international trade, as so much of it is dependent on dollar financing.

Wetherspoon would be the least of our worries. And though I’m a gold bug, a dollar superspike could hammer the “spot” price of gold – but as we’ve noted in recent letters, the spot price seems to have less and less of a bearing on the actual price of acquiring gold these days, and it would be the gold price in dollars anyway.

We’re somewhat insulated from the deflation here in the UK as we have the pound, which is no longer used as the dollar is in international finance and which the Bank of England seems very capable of inflating away. But the multinationals in the FTSE are a different matter, as are the banks in the City with their outposts in paradise…

Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at how stressed the banking system within the UK has become. And I’ll speak to Akhil Patel, who called this market panic to a tee in December, and is now sounding very optimistic about the future. But that’s all from me for today.

Debt. It’s a formidable drink – but especially when it comes in dollars.

All the best,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

For charts and other financial/geopolitical content, follow me on Twitter: @FederalExcess.

Category: Market updates