A few weeks back in this letter (Fear is in fashion –19 August), we declared that with the financial commentariat becoming so bearish, that it was high time we got a melt-up.

However, if a global recession accompanied by a bear market arrive in the near future, it will be the most well predicted of such events in financial history.

But if following the crowd made you money, everyone would be rich

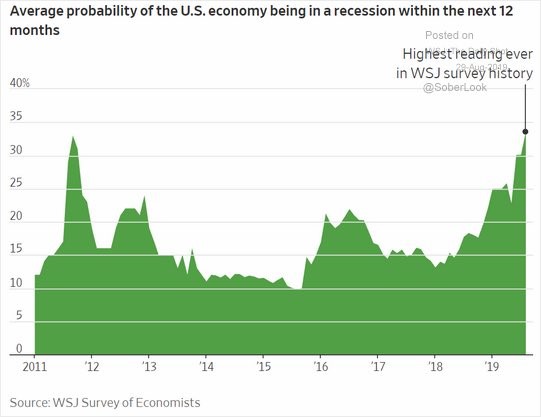

Economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal have never had such conviction that a recession is on the way…

From The Daily Shot, on Twitter

From The Daily Shot, on Twitter

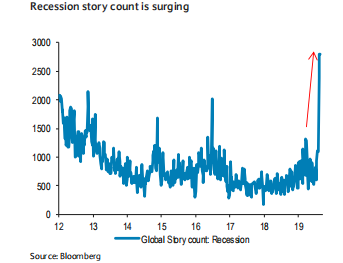

There’s a bull market in news articles about recessions…

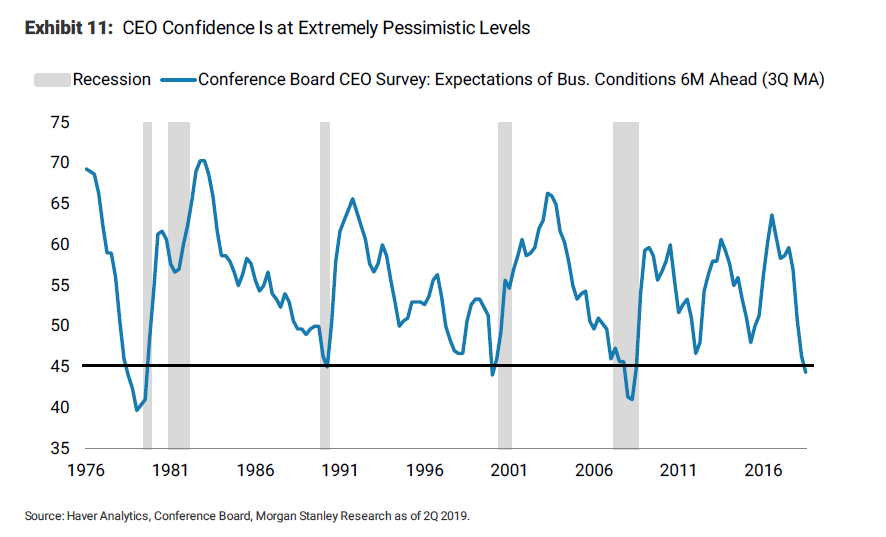

… and CEOs are reaching for the Prozac:

The sheep are on the move… but where?

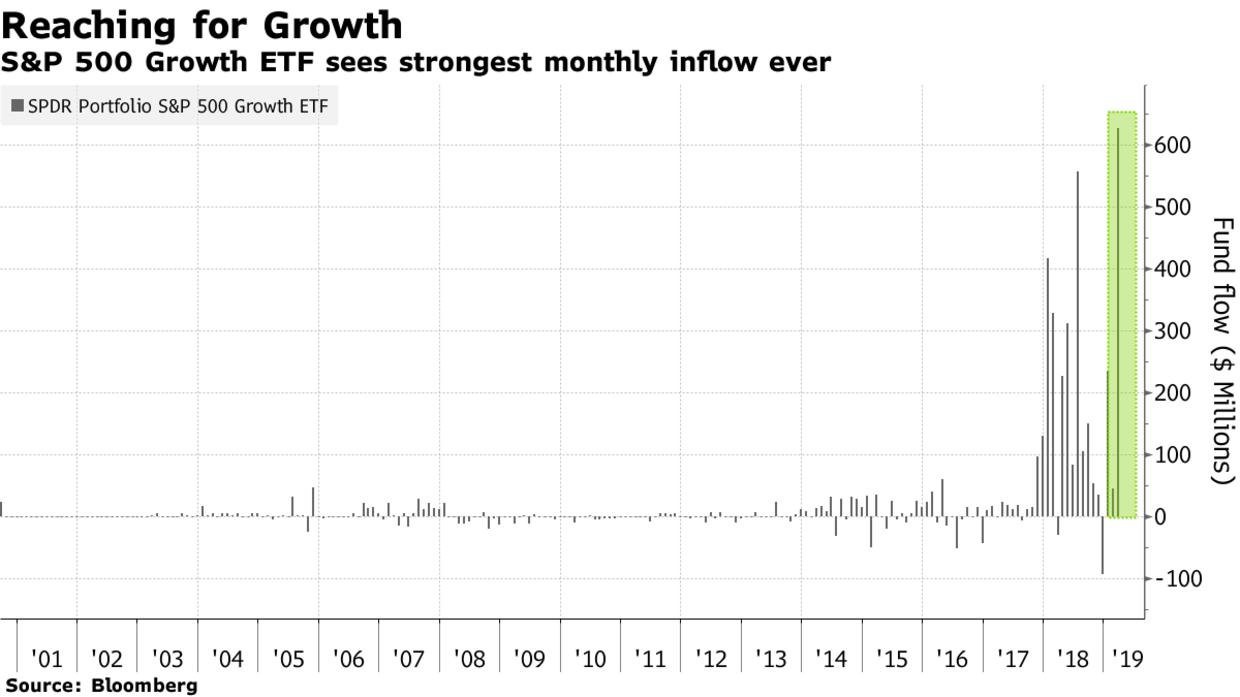

Earlier this year, some investors got very bullish on tech stocks. April in particular saw record inflows into an S&P 500 FANG tracker:

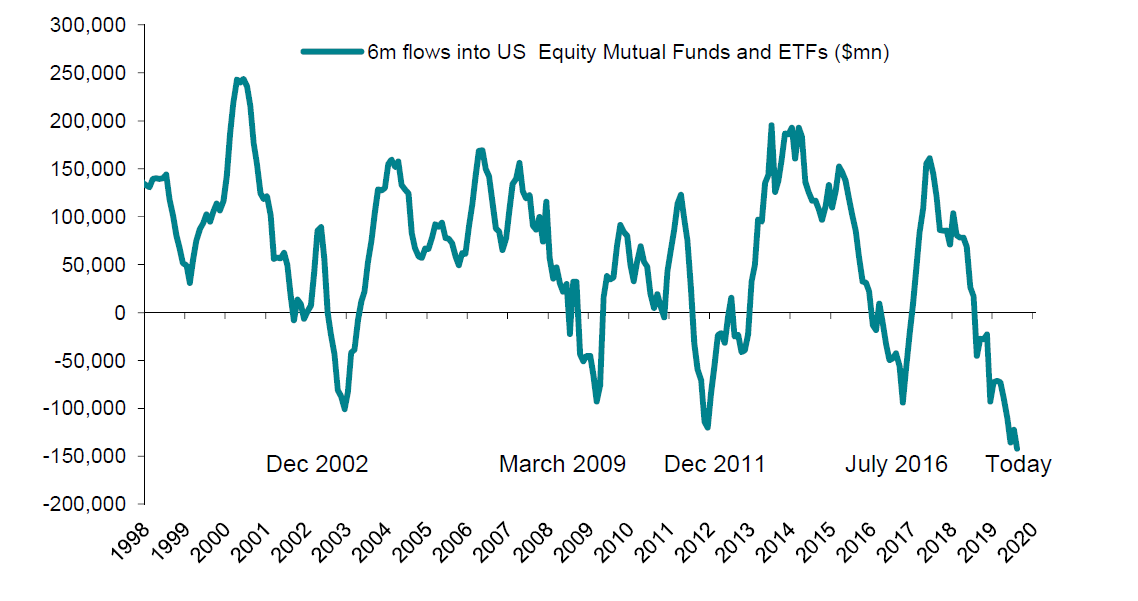

But now they’re spooked, pulling $200 billion out of US equity mutual funds and ETFs for the year on a net basis.

However, if you take at flows into stocks over the longer term, you notice something:

Whenever the money has been withdrawn from the US stockmarket to the degree it is now – March 2009, December 2011, July 2016, etc – it’s been a really bad time to sell those stocks, as there’s a rally just around the corner.

If everybody gets caught on the wrong foot now, I reckon there’s room for the US stockmarket to move violently in the opposite direction. Bitcoin’s continued claim to $10k territory, the strength of the industrial metals like platinum and palladium, are all telling me there’s still juice in the tank, bar a sudden external event like a European bank failing or Cold War II tensions suddenly getting hotter.

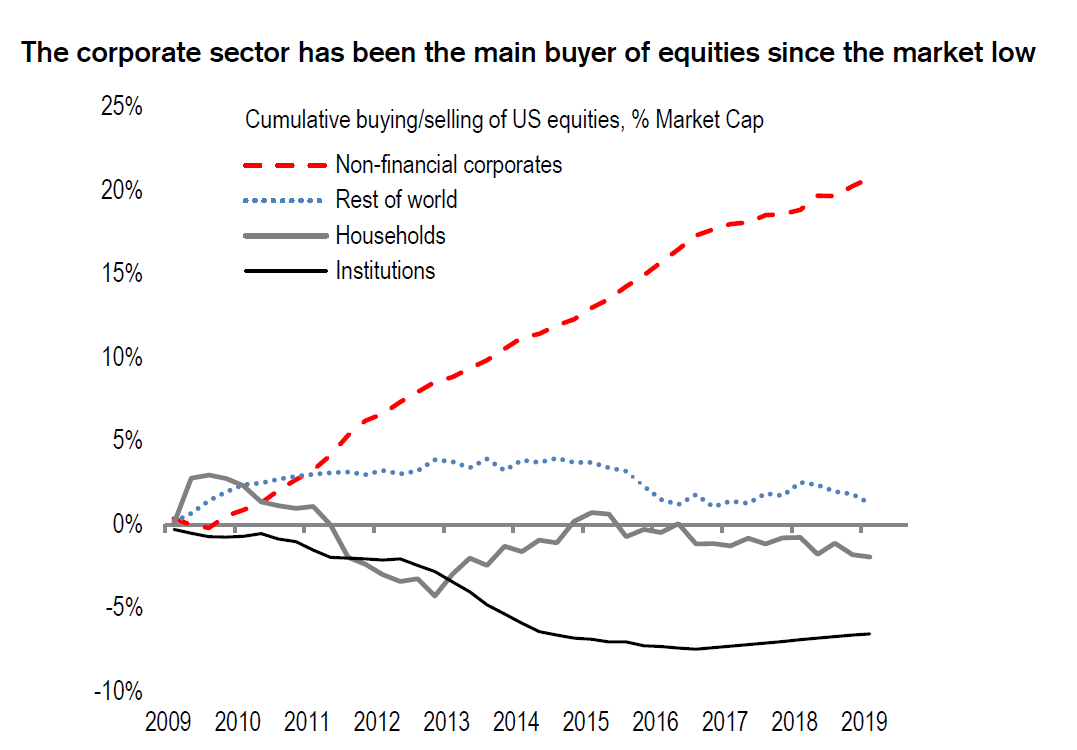

Not to mention that a key driver of this massive bull market hasn’t stopped. The US corporate sector continues to cannibalise their market by buying their own shares back:

When this cannibalism ends, there’ll be hell to pay, no doubt about it. But much of it has been energised by low interest rates, allowing the companies to borrow money cheaply and buy their shares back to enrich their executives and shareholders. And with interest rates set to become lower, this will only continue, unless the practice is outlawed – unlikely, with a president who uses the stockmarket as a benchmark of his performance in the White House.

As we’ve questioned once before in this letter, imagine how high stocks can go if companies can borrow at negative rates to buy their own shares back. It’s an abhorrence to be sure, but one investors should be prepared for as we see junk corporate bond yields go negative in the eurozone.

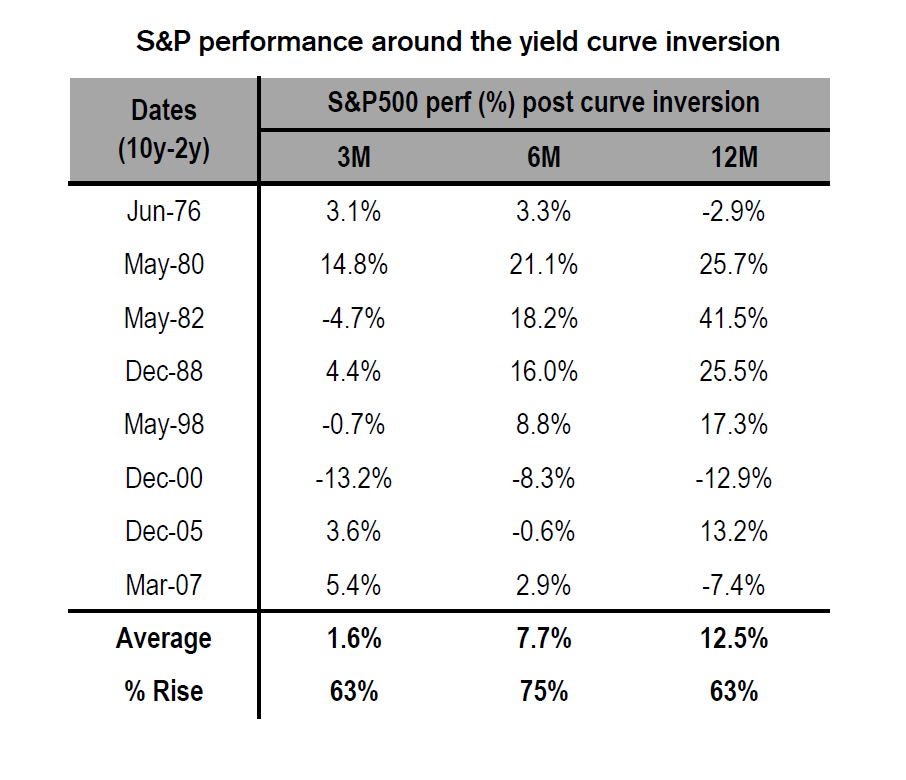

Brent Johnson, a man I hosted a podcast with some time ago, pointed out something interesting to me a while back about a recession indicator, the yield curve. Inversions of this curve – where interest rates become higher in the short term than they are in the longer term – are seen by almost everybody you can find in mainstream finance as a signal of a coming recession.

But Brent wisely pointed out that this is actually bullish for the stockmarket in the short run, as before the recession actually hits, say 18 months afterwards, speculators can borrow cheaply in the long run to invest in higher yielding assets in the short run, creating an explosive move higher in asset prices.

I found a recent table which maps out just how high this can be, and the performance of the S&P 500 three months, six months, and 12 months after each historical inversion has taken place is revealing:

With the exception of 2000, the market has always ended higher at one of those waypoints – often significantly so. And it’s why for the moment, though I’m cynical of the whole game and happily sitting with a stash of golden insurance, I reckon there’s a significant amount of juice left in the tank for a mighty melt-up. Let’s watch.

All the best,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates