It’s your last chance to celebrate it with a menthol Camel cigarette. From today on, all flavoured cigarettes and rolling tobacco are illegal to sell in this country. Get ‘em while you can.

The rationale behind banning menthols is that it will lead to a decline in kids sparking up, as menthols are a little smoother. Apparently, it’s not the responsibility of parents to stop their kids from doing it. The idea that we are responsible for our own safety (and those of our children) grows ever fainter, a fact made ever more evident under the WuFlu curfew.

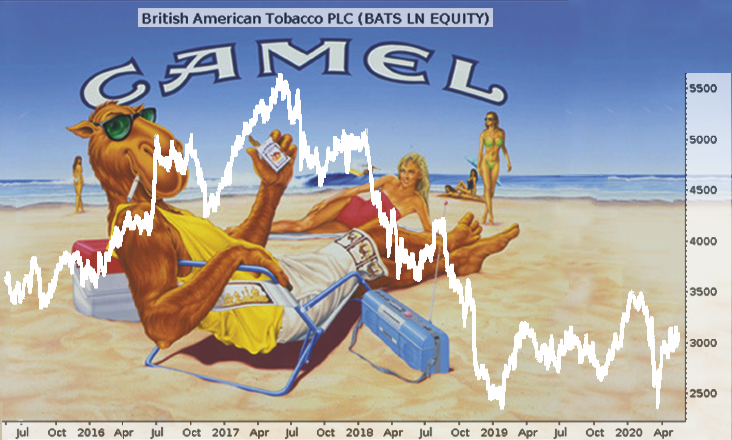

But “Big Tobacco” hasn’t been yet. British American Tobacco ($BATS), which owns the Camel brand amongst dozens of others, got crushed with everything else in March, but bounced off the same price it bottomed at in early 2019:

Smooth character: “Joe Camel”, the mascot of the Camel cigarette brand believed to be extinct, has been sighted abroad in nations with looser advertising regulations.

Smooth character: “Joe Camel”, the mascot of the Camel cigarette brand believed to be extinct, has been sighted abroad in nations with looser advertising regulations.

Source: me, on Twitter

My colleague James Allen made the case a while back that “Big Oil” would be forced to go the same route as Big Tobacco: significantly ramping up their dividend distributions to keep investors enthused in a business deemed politically incorrect. But can Big Oil afford such dividend payments when oil has been smashed as hard as it has?

With Brent crude managing to reach $35, there may be some relief on the horizon for oil producers, but right now James reckons you’d better off sticking with the new kids on the block.

Considering how much black gold has been bashed by politicos in recent years, it certainly looks like black gold is due for “the menthol treatment”. We’ve seen endowments and pension funds pressured to ditch their holdings of anything considered politically incorrect in recent years – how long before politicians get in on the virtue signalling action?

The buffeting of Buffett

The ability of camels to endure harsh conditions for ridiculous periods of time (seven months without water if the conditions are right) in the desert, and to stoically come out on top, is something of a metaphor for one of the most gruelling – and rewarding – styles of investing: value.

The iron constitution required to be a value investor is such that those with large portions of capital often opt to just give their money to a value investor rather than make the investments themselves. They turn to the likes of Tim Price who can handle vast volatility when he knows the value of what he holds is being underpriced by the market.

With that in mind, I was very interested to see Tim’s recent write-up on a camel which investors have hoisted their capital upon for decades: Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett’s holding company, which has delivered huge returns since its inception in the 60s – provided you held the share for long enough.

I’d love to show all of the terrific piece which Tim wrote for The Price Report, but for that you need a subscription. Instead, I’ll leave you with this snippet:

Between 1964 and 2019, the overall return in per share value of Berkshire Hathaway stock equated to a staggering 2,744,062%. The S&P 500 stock index delivered, over the same period, a relatively paltry 19,784%. Anyone with the luck – and stamina – to hold on since Berkshire Hathaway was a listed business will have been made a millionaire many times over.

And yet…

The main problem with any analysis of Berkshire Hathaway’s success is that these statistics are all after the fact. They tell us nothing about the future and, as that extract above makes abundantly clear, Berkshire’s near-term future, at least, looks anything but certain.

(Berkshire Hathaway reported a $49.7 billion loss for the first quarter of 2020. At his annual presentation to shareholders – done virtually this year due to the coronavirus pandemic – Buffett announced that he had sold his company’s entire holdings in American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Southwest and United Airlines, during April.

As at the end of 2019, apart from its holdings in airlines, Berkshire had significant equity interests (valued at over $248 billion in total) in American Express, Apple, Bank of America, Bank of New York Mellon, Charter Communications, Coca-Cola, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Moody’s, US Bancorp, Visa and Wells Fargo. That is practically a roll call of corporate America but in particular of Wall Street.

Those companies were highly valued before the eruption of coronavirus. How they will be valued in the months and years to come is anybody’s guess. But with the best will in the world, I suspect Berkshire Hathaway’s listed equity portfolio will enjoy, at best, a “wild ride” for the balance of 2020, and beyond. “Wild ride” in this instance is a euphemism for likely getting hammered. Its portfolio of wholly owned businesses will be, to an extent, easier to manage, in that Berkshire Hathaway enjoys complete operational control thereof, and can therefore hire, fire and fundamentally “trim” operational overhead in those subsidiaries as it desires, with complete impunity.)

… Over its long and hugely successful history, Berkshire Hathaway stock has become something akin to the magic mirror in Snow White (or any magic mirror, for that matter): it shows observers and fans of the company what they want to see, rather than what necessarily is. For those who see the triumph of Anglo-Saxon capitalism against all comers, that is what it represents. For those who see the singular success of a homely, 1950s version of American “can do” optimism, Berkshire is that, too. But as Oscar Wilde pointed out in The Importance of Being Earnest, the truth is rarely pure and never simple.

All the best,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates