Making connections and recognising patterns where none actually exist is a risk all investors face.

As humans, we’re hard-wired to do it. After all, our ancestors who didn’t make connections – like linking the sound of leaves rustling to the threat of a predator – often didn’t make it.

Thankfully, most of us aren’t at risk of being attacked by a tiger anytime soon – but that doesn’t mean our investment portfolios won’t get mauled.

“Past performance is not indicative of future results” is always displayed beneath financial promotions with a historic chart, but there’s no stopping the human brain projecting the past into the future.

Some traders use the positions of the stars and planets in the night sky to make their trades. Others simply rely on the mantra that “stocks go up over the long run” and simply buy everything in the market rather than anything specific.

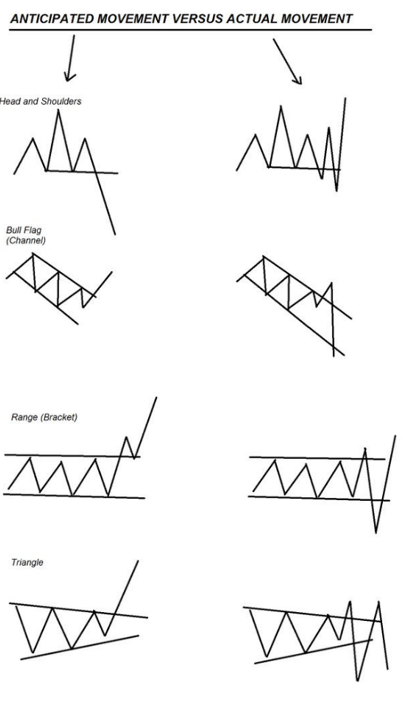

Others follow chart patterns to try and predict the future. A trader I follow on Twitter recently posted a wry comparison of how that goes:

Left column indicates “classic” patterns which if a trader can see forming, should be able to profit from before it is completed. Right column is what often happens instead.

Left column indicates “classic” patterns which if a trader can see forming, should be able to profit from before it is completed. Right column is what often happens instead.

Source: @trader_dante, on Twitter

There’s a pattern I’ve been noticing for more than a year now. The more I see, the more I’m convinced.

But I’ll let you be the judge of whether I’m gonna get mauled.

Daggers in the sky

Back in the 1950s, an aircraft was built with wings so sharp you could cut yourself on them. Special protective guards had to be placed over it when it was on the ground so the maintenance crew didn’t get sliced up on the job.

It was called the Starfighter, and it was built with speed in mind. That, and the ability to blow up Soviet aircraft – with missiles that would cause nuclear explosions in the air, if that was required.

Note the very short, trapezoid shaped wings, a radical departure from conventional aircraft design at the time. Their edges were only 0.41mm thick.

Note the very short, trapezoid shaped wings, a radical departure from conventional aircraft design at the time. Their edges were only 0.41mm thick.

Source: WikiCommons

A massive engine stuffed into a tiny airframe, the Starfighter was known as” “the missile with a man in it”, with a safety reputation to match. It went so fast that if the ejector seat launched the pilot upward he would be torn in half by the tailfin. To mitigate this, the ejector seat launched the pilot down through the fuselage, which made ejecting at low altitude lethal.

Despite its risks to pilots however, the Starfighter was a success overall. Though it had been taken from drawing board to the air in just a few years, it would become the first aircraft to hold multiple records at the same time: it was faster, could fly higher, and climb more rapidly than anything else in the sky. Such was its success that the Italians only stopped flying them in 2004.

It was a member of a group of aircraft called the “Century Series”, dubbed after their designation beginning with “100” (The Starfighter was F-104). The Century Series, rapidly designed and manufactured, would push what aeroplanes were capable of, in terms of performance and onboard electronics, suddenly much further into the future.

Second century

If you’ve been reading Capital & Conflict for a while now, you’ll likely have heard my argument that we are at the onset of a second Cold War. The more I look, the more connections I find between today and the beginning of the first Cold War, when nobody quite understood just how deep and dangerous the rift was between East and West.

And low and behold, just last week we’re seeing a push from the Pentagon to get a Century Series fit for the 21st century on the road.

From Defense News, emphasis mine:

The U.S. Air Force is preparing to radically alter the acquisition strategy for its next generation of fighter jets, with a new plan that could require industry to design, develop and produce a new fighter in five years or less.

On Oct. 1, the service will officially reshape its next-generation fighter program, known as Next Generation Air Dominance, or NGAD, Will Roper, the Air Force’s acquisition executive, said during an exclusive interview with Defense News.

Under a new office headed by a yet-unnamed program manager, the NGAD program will adopt a rapid approach to developing small batches of fighters with multiple companies, much like the Century Series of aircraft built in the 1950s, Roper said.

“Based on what industry thinks they can do and what my team will tell me, we will need to set a cadence of how fast we think we build a new airplane from scratch. Right now, my estimate is five years. I may be wrong,” he said. “I’m hoping we can get faster than that — I think that will be insufficient in the long term [to meet future threats] — but five years is so much better than where we are now with normal acquisition.”

… the point, Roper said, is that instead of trying to hone requirements to meet an unknown threat 25 years into the future, the Air Force would rapidly churn out aircraft with new technologies — a tactic that could impose uncertainty on near-peer competitors like Russia and China and force them to deal with the U.S. military on its own terms.

Imagine “every four or five years there was the F-200, F-201, F-202 and it was vague and mysterious [on what the planes] have, but it’s clear it’s a real program and there are real airplanes flying. Well now you have to figure out: What are we bringing to the fight? What improved? How certain are you that you’ve got the best airplane to win?” Roper wondered.

“How do you deal with a threat if you don’t know what the future technology is? Be the threat — always have a new airplane coming out.”

The post-Cold War world allowed the US to spend 15-20 years on new aircraft projects, working only with a few monolithic companies, as there was no foreign competitor to drive the innovation required to beat the Soviets. But with the rise of China, that’s all changed – rapid innovation is required, and time now comes with a price once again.

In an issue of Zero Hour Alert earlier this year, I made the prediction that commericial drones would become the AK-47 of this Cold War, as it grants the user the same asymmetric advantages over conventional foes as the Kalashnikov did. The recent drone attack in Saudi Arabia has given more weight to this view – one of the stocks I listed as a play on this idea zoomed 20% right after the attack, and is up 400% since the issue went out. In fact, of the five investments I listed in that issue, only one is down since then.

If we get a new Century Series out of the aviation industry, there’ll be further Cold War opportunities for investors. If realised, a new Century Series aircraft would be created by a small, highly specialised design company who would test its functionality purely as a digital model with advanced software. It would then be entered into contest against other design shops, and the winning blueprint would be made by a separate manufacturing outfit.

The idea is to make the aviation industry much more like the car industry – after all, it seems strange why they don’t function similarly. But to get there would mean a total flip in the status quo, and tilt the scales in the favour of the smaller, nimble companies.

Who’s behind this idea? Dr Will Roper, a charismatic Rhodes Scholar at the Pentagon with an Oxford PhD on String Theory. Maybe it’s just me making connections when I shouldn’t, but he seems to like a modern “Whiz Kid” of Robert McNamara’s era – the US defence secretary under JFK…

All the best,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates