Turkey’s crisis is nothing to worry about. Because if it wasn’t Turkey, it’d be someone else.

What should worry you is the timing of the Turkish crisis. The world has barely embarked on quantitative tightening or interest rate increases. And already, debt crises are breaking out.

Back in May I warned you about all this. Argentina had approached the International Monetary Fund for assistance. And “Turkey looks to be next,” I wrote.

Turkey’s problems are fairly straightforward. It has huge foreign currency denominated debt. About 70% of GDP when you add together corporate, government and financial sector debt.

When the currency begins to slide, that debt becomes less affordable. And the Turkish lira is downright tumbling.

But the focus on Turkey is missing the bigger picture.

The interest rate and crisis cycle

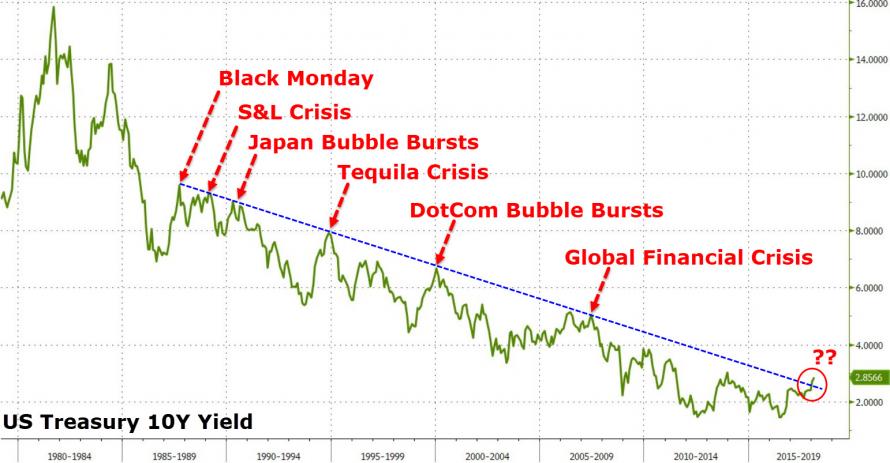

For 35 years, debt has become steadily cheaper. That’s why the world has seen such an extraordinary debt bloom. Government debt to GDP, the average mortgage, student debt, credit cards corporate debt and every other form of debt have all surged. Especially in Britain.

But it hasn’t been smooth sailing. Each time interest rates spiked on their 35-year downtrend, we saw some sort of financial crisis. Then rates are cut. It’s an extraordinarily consistent cycle.

Let’s take a look at the US experience, which dominates interest rates around the world.

In 1987, the US ten-year Treasury yield spiked from 7% to over 10%. Then came the famous Black Monday, when stock tumbles set records.

In the 1990s, countries in Asia and elsewhere had their crises at interest rate peaks.

In 2008 it was sub-prime borrowers in the US who suffered when rates rose.

2012 it was European governments.

We also had the taper tantrum of 2013. John Authers has an excellent new video out at the Financial Times comparing the 2013 taper tantrum to today’s Turkey crisis.

Both times, the prospect of Federal Reserve tightening kicked emerging markets in the teeth. In 2013, the Fed delayed its tightening of monetary policy, allowing emerging markets to stabilise. Will the new Fed chair do the same, or plough ahead with its rate hikes this year?

When US interest rates spiked in January of 2018, they triggered a 10% correction in the US stockmarket.

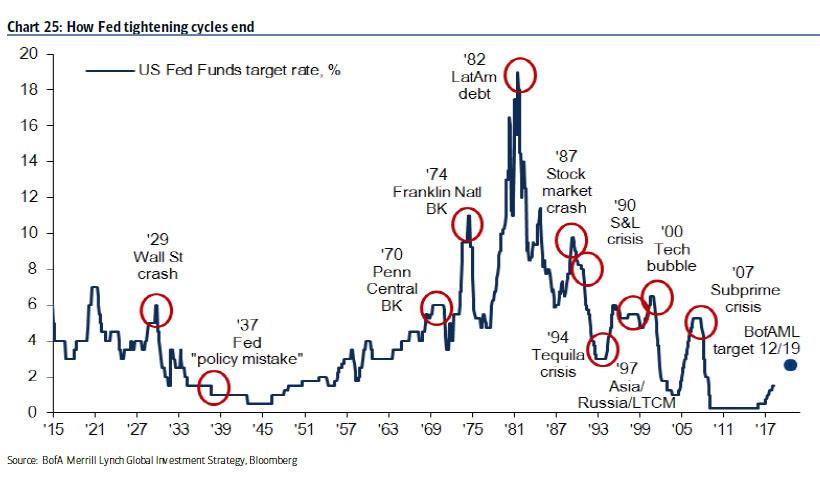

This chart from Bank of America shows the same phenomenon going back much further. Each rate hike cycle is followed by a crisis.

Well, interest rates are entering an upcycle once more. I don’t know whether this is the beginning of a major bull market in interest rates that will last decades, or just another blip on the 35-year downtrend. It doesn’t matter. The point is, eventually a crisis somewhere will signal the end of the cycle.

Let’s quickly look at what’s making rates go up.

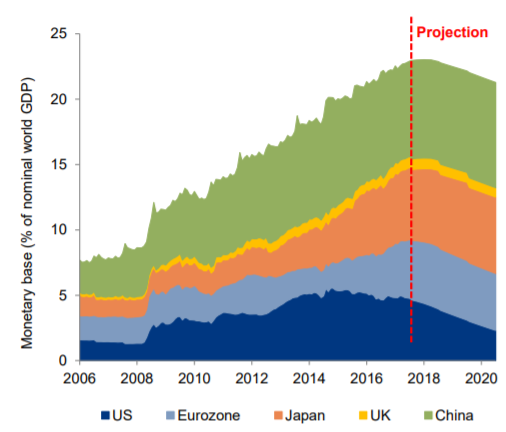

Thanks to inflation, central banks around the world are expected to raise interest rates. The European Central Bank (ECB) will be winding up its quantitative easing (QE) in December, with recent ECB comments suggesting there might be a rate hike next year.

This chart shows how central banks in the world put together will begin reversing QE this year, something pundits are calling quantitative tightening (QT).

Source: Allianz (Dec 2017)

Source: Allianz (Dec 2017)

Given most of this QE was spent on government bonds, ending the purchases will drop the biggest buyer out of the market. That means higher borrowing costs.

So monetary policy is likely to continue tightening. Especially with unemployment at extraordinary lows and US GDP growth at highs.

But a quick glance at the first two charts above tells you where all this ends.

Who is the weakest link?

Given the proven propensity of a crisis to occur while borrowing costs are rising, when interest rates begin their upcycle, you have to scour the world for the weakest hands to discover the source of the coming crash. Who will snap first in a world where debt is becoming more expensive?

Is it sub-prime borrowers, who borrowed more than they can afford based on rising house prices? Perhaps companies, who borrowed too much when times were good? Or tech stock-buying margin borrowers, who face margin calls from their lenders when stocks correct?

In mid-2018, it is Turkey.

But does it really matter who it is?

Of course it does if you have ties to Turkey. The Spanish and Italian banking system are caught up in the Turkey contagion thanks to their loans. The British banking system lends Turkey far less. Although that’s a little misleading because the British banking system lends to the banks that lend to Turkey…

But we’re getting bogged down in details again.

My point is that the really remarkable thing here is how quickly the Turkish crisis popped up. We’ve barely even begun the interest rate upcycle. The ECB hasn’t raised rates. The Bank of England has barely begun. And the Fed’s rates are still extraordinarily low.

If countries are already having emerging market debt crises, it’s the timing that’s terrifying.

My worry isn’t so much that Turkey is a canary in a coalmine. Nor that it will unleash some sort of contagion. Although both are possible.

Instead, the real concern is that Turkey’s crisis comes so early in the rate hike cycle it signals how sensitive the world is to higher rates.

As Ambrose Evans-Pritchard puts it, “Turkey is the first big victim of Fed tightening, but it won’t be the last.” Far bigger failures are looming.

Neither borrower nor lender be?

It’s not just that the world has borrowed more money than ever before. Investors have pushed the boundaries too.

Yesterday, Boaz Shoshan took you on a journey through the odd world yield investors find themselves in. People have invested in stranger and riskier things to dig out returns as interest rates fell.

When the interest rate worm turns, they’ll be struck first.

All this adds to the urgency of Boaz’s and my work over at Zero Hour Alert. We’ve come at the problem from two angles. You have to be able to profit from a crash. And you have to keep some of your wealth outside the fragile financial system.

Wherever the eventual crisis and crash comes from this rate hike cycle, both will pay off handsomely.

Here’s how you get access to our reports.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates