So it turns out worldwide lockdowns are pretty bad for the economy. Who knew?

Bearing the brunt of this, of course, are commodity prices. For them, 2020 has been a bloodbath.

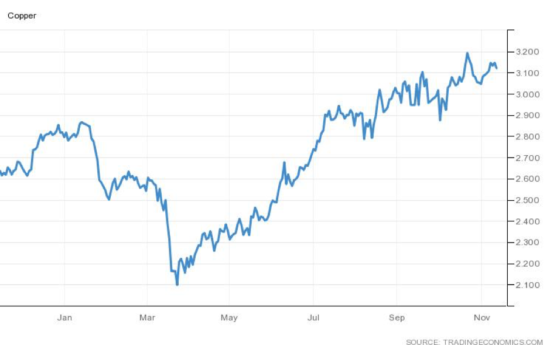

Oil briefly dipped below 0USD per barrel for the first time ever. Copper – nicknamed “Dr Copper” due to its role as a barometer for the health of the global economy – tumbled by over 25% in March compared with the year before. As we sat at home watching Netflix and fantasising about our next trip to the pub, industrial commodities were being shaken as consumption nosedived.

To give you an idea how just how rough the first half of 2020 was for, consider this: the Bloomberg Commodity Index Total Return fell from a high of 173.66 in January to 126.86 in mid-March – that’s over 25%.

But even though it’s been a pretty grim time to be, say, an oil producer recently, that could be about to change. We could be on the cusp of a new commodity supercycle.

Although those of us in England are back to languishing under lockdown, the rest of the world isn’t.

China, in particular, is back in business. It’s been one of the key drivers of commodity price recovery – particularly oil – in the second half of this year. Between January and July, China’s imports doubled compared with the same period last year. And as the graph above shows, industrial commodities have been climbing upwards for a few months and are beginning to approach the peaks we saw in 2018. It is, at the time of writing, the only major country to post positive GDP growth this year.

And as you can see on the graph above, prices are already recovering pretty sharply.

But in commodity markets, prices can become unmoored from their long-term averages fairly often. Sharp spikes and falls in prices aren’t unusual.

Why is that?

Because, generally, it takes a while to bring new supply online. The price of copper may be high now, for example, but if you want to open a copper mine it’s not going to happen overnight – sorry to crush your dreams.

So demand can continue to rise before supply has a chance to catch up.

And the news of a potential vaccine in the near-future could mean the bounceback in demand will be sharper and happen sooner.

The pandemic has brought about some changes that have pushed up prices which could be here to stay.

Take supply chains, for example. You’re (probably) wearing clothes right now. It’s likely that what you’re wearing wasn’t made in one country. Cotton can be grown and harvested in one country, processed in another and shipped elsewhere to be sewn together to make clothes. Fears surrounding infection, particualrly cross-border, could slow trade between countries for a long-time to come.

No doubt, Monday saw some promising news about a vaccine. But big question marks remain over the pace of distribution – particlularly to developing countries where those of us sat in the West tend to buy things from.

So, if we’re seeing a lack of investment in supply, then as demand rises we could see a spike in prices. That’s exactly what Variant Perception, an asset management firm, forecast for crude oil – for a few years now, the average oil company hasn’t exactly been greeted with open arms by banks.

Monetary policy reaching its limits?

Let’s step back for a moment and view the pandemic in the context of the past decade of monetary policy.

In much of the West, interest rates have been low – very low. In the case of some countries – I’m looking at you, Japan – they’ve turned negative. On top of this, quantitative easing (QE) has been used to grease the wheels of the financial system and pump liquidity into the markets since the financial crisis.

Low rates also mean lower costs of borrowing for governments, so this has come in fairly handy during the financial crisis and the current pandemic where spending has gone through the roof.

And in some ways, it looks as though the line between fiscal and monetary policy is becoming increasingly blurry.

At the onset of the pandemic the government came pretty close to insolvency, as Andrew Bailey told Sky News in June. Without support from the central bank – in the form of buying Treasury bills through QE – the government could well have faced issues funding itself in the midst of the market turmoil.

All of that is to say: as economies in West have stumbled, central banks have been taking up the slack to help keep them going. Fiscal and monetary policy are becoming increasingly intertwined.

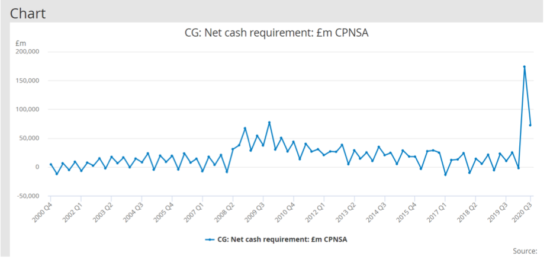

The UK’s net cash requirement since 2000

The UK’s net cash requirement since 2000

Source: Office for National Statistics

So fiscal policy is becoming ever-more expansionary and central banks are adding a larger and more varied array of assets to the balance sheets.

When you throw in the boost to commodity prices outlined above, we get the perfect recipe for inflation.

And how have investors braced against a rising tide of inflation in the past?

Physical assets.

If you’re interested in finding out more, then next week we have a big announcement for you. Charlie Morris, editor of The Fleet Street Letter Wealth Builder – who made his name managing over £3 billion in the City – will be here with a plan to help you navigate the markets over the coming year.

And commodities play a pretty special part in that plan.

Watch this space.

All the best,

Nathan Tipping

Research Analyst, Southbank Investment Research

Category: Market updates