Today’s letter comes from Eoin Treacy, who wanted to expand on a crucial flaw in the UK economy which he believes will drive. It all comes down to a simple metric so basic that’s it’s often overlooked – despite its significance. I’ll let him brief you on the details.

Back tomorrow,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

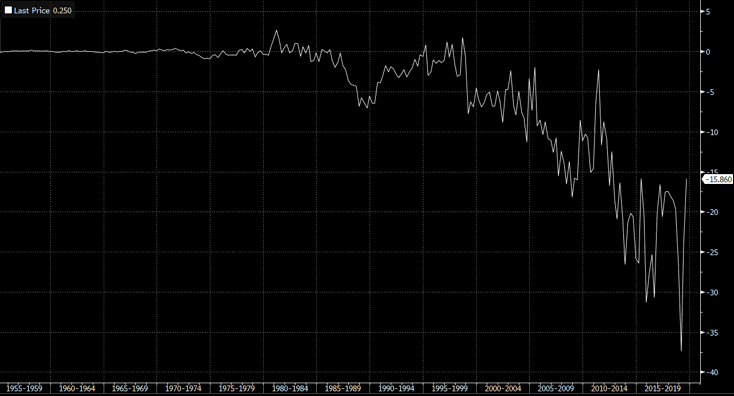

The balance of payments is something that is so easy to understand that it seems to get ignored by politicians.

It’s a pretty simple metric: you just take everything a country spends on imports and take it away from everything it earns on exports. When a country has more imports than exports, there is money flowing into it. I think we can objectively conclude that is a good thing. Of course, the opposite is also true. If imports outweigh exports, it means there is money flowing out of the country.

(It’s very easy to quibble around the edges with this simple metric because assembly operations often rely on importing components from a number of other countries before they are combined elsewhere to create a higher value item which is exported. This way of measuring the balance of payments tends to overstate the benefit; it’s basically the “sum of all parts” argument often used by China to play down its dominance of the global manufacturing sector, but I digress.)

For the UK, the majority of high-end manufacturing is in the aeronautics and automotive sectors and it relies on a lot of parts being imported from abroad. These sectors flatter the balance of payments metric but it is still negative.

This was not always the case. For much of the period between about 1955 and 2000, the UK’s balance of payments bobbed around zero. Some years it was positive, others negative but generally it was trendless. That period was associated with growing prosperity because as productivity and living standards improved, so did consumption.

But something happened in the early 2000s that upset that balance.

UK balance of payments since the 1950s

UK balance of payments since the 1950s

Source: Bloomberg

The UK has since slid into persistent deficit territory.

I believe there are two reasons for this. The first is China gained accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in the early 2000s and manufacturing quickly migrated there lock, stock and barrel. Manufacturing had been in terminal decline in the UK ahead of that event but China entering the WTO was the death knell. To add insult to injury, the UK became a net energy importer in the mid-2000s.

There is no quibbling about an energy deficit. It’s something I have been banging on about for as long as I have been working with Southbank Investment Research. The UK used to be an energy exporter but for much of the last decade it has imported billions of pounds’ worth of oil, gas, coal and electricity every year.

Let’s keep this simple. Between late 2013 and the end of 2019 the UK was a net energy importer. There is a lot a movement in the UK energy market because much of the oil produced in the UK is shipped to the Netherlands for refining and some is reimported. Nevertheless, until 2012 exports exceeded imports and they’ve been negative since.

UK oil imports versus exports since 2008

UK oil imports versus exports since 2008

Source: Bloomberg

This is not rocket science. The UK has an energy problem on top of its manufacturing problem and that is before we even begin to think about the challenges of public opinion turning against the fossil fuel sector and championing wind and solar. Personally, I’ve never seen a wind farm where there weren’t at least some of the turbines closed down for some reason or another.

The new Conservative administration is at least supportive of building new nuclear power plants but the only way they are going to be viable is if the cost of electricity is kept under control. The problem there is no one wants to build reactors for us at prevailing electricity prices (Hinkley Point’s damning economics being a case in point).

Believe it or not, the answer to the UK’s energy problems are all around us. It’s sitting in geothermal vents in Cornwall waiting to be tapped but that’s ignoring the world-beating expertise the UK has in generating hydrogen. The UK is home to bleeding-edge companies in the hydrogen sector pioneering everything from developing hydrogen production to designing fuel cells, and the number of international partners these companies have developed is truly impressive.

From an investment perspective I am particularly drawn to the prospect of hydrogen because it is brand new. You are going to see arguments in the public sphere over whether hydrogen or battery-driven vehicles will ultimately prevail. Personally, I think it will be electric for regular cars and hydrogen for haulage and shipping. Meanwhile, server farms are already installing fuel cells to power their operations. However, that argument misses the whole point.

We have spent decades building battery factories and developing lithium-ion technology. Some fantastic success has been had but the more energy dense batteries have a greater risk of overheating. That makes progress slow.

Hydrogen by contrast is having a moment because there is no infrastructure so there is plenty of runway for development even if in the end it is not the biggest fuel source in the world. However, it is easier to iterate on the technology because energy density is not the issue. The challenge with hydrogen is in production.

The key piece of investment information is it is simply easier for hydrogen companies to come up with a new piece of kit that will double production volumes than it is for battery companies to double energy efficiency. That’s where the investment thesis and growth argument arises, and it is where the UK has room to excel.

The UK has the companies and is initially developing hydrogen from natural gas. More recent discoveries point towards the future where renewable sources can be used to turn seawater into hydrogen. As an island nation we have plenty of sea water. As a major energy-producing nation, we have ample pipeline and offshore drilling infrastructure. As an energy technology innovator, the UK has the knowhow to make it happen.

Therefore, this is an easy prediction. Within the decade, the UK will be among the world’s biggest producers of hydrogen and it will be among the biggest exporters of hydrogen-related technology. That is going to be a major ingredient in the evolution of better standards of living for the UK as we plot our escape trajectory from the EU.

All the best,

Eoin Treacy

Investment Director, Frontier Tech Investor

Category: Market updates