I’ll be away from Capital & Conflict for the next few of days – I’m currently working on an exciting side project behind the scenes that needs a bit more polish before I can share it with you.

I’ll be back on Friday. In the meantime, however, I’d like to share with you a report we’ve been writing for new subscribers to Capital & Conflict. It’s about inflation – that old monetary enemy we think is due for a comeback once the dust has settled on the WuFlu crisis. We’ve written a lot about this in recent months – but we’ve packaged it all together here so it’s all in one place. I hope you enjoy it – this one’s on the house.

The below is part I – stay tuned for the second act coming tomorrow.

Until then,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

PS Inflation is an ever-present threat for all savers – but in our world of bank bail-ins and “Unexplained Wealth Orders”, it’s hardly the only one out there. The purpose of our latest free e-letter service, Fortune & Freedom, is to keep you abreast of the “enemy action”, and keep you protected from it – sign up to the daily briefing here.

The return of inflation

Part I: a new era

Chances are, you aren’t one of the 1 in 50 Britons old enough to remember World War II.

But if you have memories of the 1960s and 1970s, you can still remember the economic aftershocks of the war, when Britain’s government struggled to pay back the epic levels of debt. Taxes tripled for some Britons, and a 25% purchase tax was just one of the burdens everyday citizens shouldered to chip away at a national debt that stood at £1.1 trillion in today’s terms.

Now, of course, the United Kingdom is fighting a war against a very different sort of enemy.

And compared to the fight against Covid-19, Britain’s war debt looks like small fry.

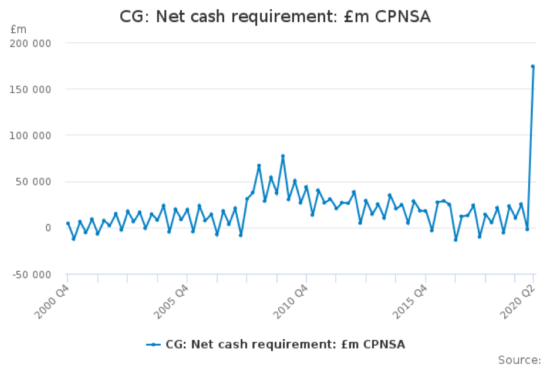

In the second quarter of 2020, the government borrowed a peacetime record of £128 billion – more than double 2019’s annual deficit. That borrowing spree has now pushed Britain’s debt to around £2 trillion and counting.

At first glance, it doesn’t look too bad. In 1946 UK debt-to-GDP peaked at 258%, whereas today is stands at over 100% of GDP. But this stat alone doesn’t tell the full story.

In the 30 years following the war, GDP grew in nominal terms by 8.8% a year on average, which amounts on average 2.3% annual growth once inflation is taken into account. With the growth rate higher than the 3.6% average effective interest payment, Britain’s debts could be kept at bay.

But today’s outlook is radically different, as Britain’s economy shrinks from the harshest recession in decades while piling on historic new levels of debt each quarter. And Chancellor Rishi Sunak isn’t finished with his cheque book just yet either.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) currently projects a £372 billion deficit this fiscal year, while the Debt Management Office is planning to raise £385 billion in the first eight months. The Financial Times puts this into perspective: “the UK government is on course to sell more than half a trillion pounds of debt this year, more than double the previous record at the height of the financial crisis.”

Source: Office for National Statistics

Source: Office for National Statistics

Covid-19 has pushed Britain’s financial position to a point where the usual means of debt management are no longer feasible.

Keynesian stimulus? Austerity? Raising taxes?

These are now old solutions to old problems.

I know it’s easy to become numb to the latest spending and borrowing figures… to conclude that Britannia will continue to muddle along as she always has, while our politicians rack up more and more debt.

But you and I know better, dear reader.

You surely already know in your bones that debts don’t just disappear… and that bailouts have consequences. As history and simple arithmetic reveal, there are only two ways out of this – and only one that is politically feasible for our government to enact.

It’s the same trick the government used following the Second World War to reduce its debt at the expense of investors.

It’s the invisible tax you’re already paying

“Financial repression” refers to a scenario where interest rates are kept below inflation.

Typically, when inflation rises so do interest rates, as central banks move to keep inflation under control. It’s vital for savers and investors that this happens too, as they require higher returns to offset inflation. If inflation is higher than the prevailing interest rate, there is no way of preserving your purchasing power without taking on investment risk.

Inflating away debt is difficult, even dangerous for governments, because investors generally have the option to sell that government’s debtor its currency itself when inflation picks up.

But what if investors are not allowed to escape bonds, or the pound? And central banks allow inflation to surge without raising interest rates?

That would be financial repression, and it’s exactly how governments get away with inflating away debt at the expense of the average investor.

If a government let inflation off the hook but refused to raise interest rates, then the return on bonds is likely to be lower than the losses from inflation – which is known as “negative real rates”.

This isn’t just speculation, either. If you grew up in the 60s and 70s, you remember this is exactly what happened. It’s why the interest rate on government debt was below inflation for 24 of the 30 years following the Second World War.

Inflation – and financial repression – is a tax in all but name. A tax aimed specifically at your hard-earnt savings. But before we get into why inflation is on the horizon and, more importantly, how you can protect your investments, let’s dig into how the government is going to find its way off debt mountain in one of the most underhand ways possible…

It’s not technically a default

When a government can’t pay its debts and can’t raise any more money… what’s happened to it?

Your first answer will probably be that it’s gone bust.

And by this definition at least, Her Majesty’s Government almost went bust in March. Check out what Andrew Bailey told the Guardian in an interview back in May:

Britain nearly went bust in March, says Bank of England

Britain came close to effective insolvency at the onset of the coronavirus crisis as financial markets plunged into turmoil, the governor of the Bank of England has said.

Laying bare the scale of the national emergency at the early stages of the pandemic, Andrew Bailey said the government would have struggled to finance the running of the country without support from the central bank.

Asked in an interview with Sky News what would have happened had the Bank not intervened, Bailey said: “I think the prospects would have been very bad. It would have been very serious.”

“I think we would have a situation where, in the worst element, the government would have struggled to fund itself in the short run.”

So the money-printing central bank saved the day and allowed the government to dodge default. In our book, that means it went bust.

But the chancellor’s cheques never actually bounced

Rather than allow the government to fall short, the Bank of England swooped in to save the Treasury.

This isn’t, admittedly, all that surprising.

A technical legal default was never on the cards – if it was, it would be front-page news. Modern governments aren’t prone to going “bust” in quite the same way as companies and individuals largely due to the ability of central banks to print money.

Now, central bankers would be keen to point out that they did not lend money directly to the government back in March. Instead, they forcibly calmed the the bond market. That’s implicit in their legal mandate to conduct monetary policy via the bond market – that’s where they set the interest rates you hear about on the news.

On paper, central banks are supposed to manipulate interest rates without financing governments directly. Nowadays, this is more or less a false distinction. The state of government finances is so dire that central banks are forced to finance them in order to carry out their legal mandate of stabilising bond markets.

When the chips are down and central banks have to choose between monetising the government’s debt or letting them go bust, they will always choose the former.

This marks a sea change in the relationship between the government and central banks. If you’re the Treasury, then you no longer have to worry about going bust – the Bank of England has your back…

Category: Investing in Gold