FTSE down 2.5% on Friday. As I write this, things are a little quieter. And today is Labor Day in the US, so the markets are shut.

That gives us a little breathing space to return to one of our key themes here at C&C – the dangerous ways the authorities try to ‘control’ an out of control financial system.

First up: this isn’t just a financial problem. In times of trouble, central authorities always respond by imposing restrictions and constraints on the people. Sometimes this is in the name of stability and the public good.

Often it’s not

Let’s take a really simple example. Have you ever heard of the police tactic known as ‘kettling’ during public protests?

This is essentially where the police pen protestors into a tightly controlled area, create a restrictive boundary around them, and closely monitor everyone going in or out. Protestors can find themselves caged in by the police for hours at a time, sometimes with no access to basic necessities such as food or water.

As the human rights lawyer Michael Mansfield QC put it several years ago:

“A distinctive disincentive to the collective public voice, however, comes from the introduction of a tactical option which can and has impacted dramatically upon the freedom of movement of ordinary peaceful protesters and even accidental bystanders.

“Both can now expect the real risk of incarceration for long periods of time, eight or nine hours, without basic facilities, should they be in the wrong place at the wrong time. They need have done no wrong and committed no offence. Presence is all that is required. The tactic has become known progressively as “corralling”, “containment” or “kettling”.”

Some people will no doubt see this as ‘for the public good’. We’ll leave that debate for another day. But the underlying point is: when a situation threatens to get out of hand, the authorities respond by forcibly imposing control.

Let’s take another example – the migrant crisis

You’ll no doubt have seen the images over the weekend: the endless lines of refugees snaking their way across Hungary towards the Austrian border.

It’s clearly a contentious issue. And judging by the numerous messages we’ve received about it, it’s something we should come back to later in the week. But for now let’s stay on topic. What was the first thing the Hungarian government did when the situation threatened to get out of control?

They shut the borders, shut down the transport system and left many people stranded where they were.

Limit choice.

Restrict freedom.

Lock the system down

This is the playbook for keeping a crisis under control. Same goes in the financial world.

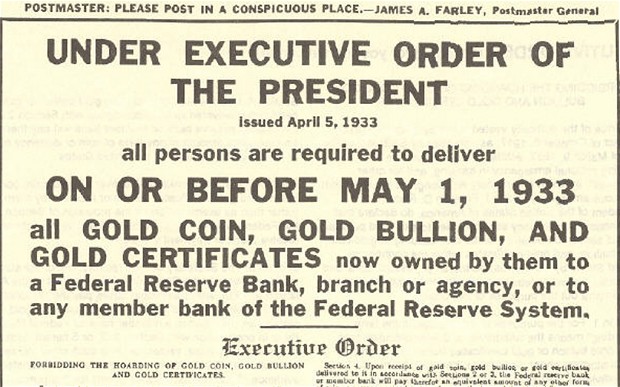

Another example. Most people have heard of Executive Order 6102. It came as the US government tried to control the escalating problems caused by the Great Depression. And it forced all US citizens, partnerships and corporations to hand over their gold.

What would you have done? Hoarded your gold – or submitted to the new law and coughed up?

Unsurprisingly, most people were unwilling to break the law. Noncompliance meant a $10,000 fine or ten years in prison. Or both. The government had hijacked the gold supply. Fort Knox filled up with gold that had been forcibly taken from private citizens.

The economy was in trouble. The authorities responded as they always do. They locked the system down. They gave people no choice.

In today’s world, it’s even easier to impose this sort of control on the financial system. Back in 1933, when the government demanded people’s gold, it was a physical transaction. People had to actually hand their gold over. If they didn’t, the authorities had to go out chase them down.

These days, most transactions are virtual or electronic

People trade stocks and bank online. Many economies are moving towards an electronic, cashless economy.

This means the authorities can lock the system down at the touch of a button.

Let’s take two examples. Earlier in the year, when it looked as if Greece could be ejected from the euro and Greek banks were haemorrhaging cash, the authorities closed the financial system down. The stockmarket shut. The banks closed their doors. People had to queue up at the ATM for their daily ration of cash. Regular people were essentially shut out of the financial system.

In a cashless society, it’d be even easier to do this. Impose a limit of £50 a day on people’s debit cards. Anything above that and it’d be ‘transaction denied”.

Another example – China. At one point, almost half the stocks on the Shanghai Stock Exchange were suspended. You couldn’t buy them. And if you needed to sell, you were out of luck. You were stuck.

Make no mistake, this kind of thing could happen in Britain, too.

Category: Geopolitics