The tide is going out on globalisation.

It’s that time of the night where everyone left at the great globalisation party of early 21st century is comprehensively drunk. But the lights have come on and revealed the rubbish on the floor and the dishevelled clothing of the revellers.

The bar staff are sweeping the floor and stacking chairs. Some people are too far gone to know that they should have left hours earlier.

You can’t blame people for liking a good party. Everybody loves a free drink. Just like everybody loves a parade.

But you can blame people for not heeding the warning signs that the party was over. Every crisis born of a financial bubble evolves in basically the same way: the financial excess becomes a financial crisis; the financial becomes economic; the economic becomes political; the political becomes geopolitical.

The rise of political instability in the ‘advanced’ economies is political conflict. Tony Abbott, the leader of Australia’s Liberal-National coalition government, is ousted by former Goldman Sachs man Malcolm Turnbull. Here in Britain, the Labour party has warmly embraced its trade union roots.

National interests

In less than 500 days, America will elect a new president and the leading candidates for each party are a socialist and a serial bankrupt, respectively. Germany is leading the way in Europe, first by embracing a human wave of immigration. Second, by building a wall to keep the next wave out.

The ‘conflict’ in each country is over what the national interest is and how to attain it. Is it in Scotland’s national interest to remain part of the UK? Is it in Britain’s national interest to remain part of the EU? What is in Britain’s national interest? Or should Britain simply be a global citizen and act in the best interests of all?

That very conversation – that nations have interests and those interests must be articulated and then defended – is the type of conversation you’ll see more of in the coming years. It will be a renaissance of the geopolitical. That power comes from geography as much as it comes from the barrel of a gun.

None of that, however, is the kind of conversation you have in a financial boom. You don’t have to. The credit boom is good for everyone. The bust forces you to take sides and fend for yourself.

That’s the ‘capital’ aspect of today’s letter

“We have seen this burst of globalisation, and now we’re at a point of consolidation, maybe retrenchment. It’s almost like the timing belt on the global growth engine is a bit off, or the cylinders are not firing as they should”, says Robert Koopman, the chief economist for the World Trade Organisation.

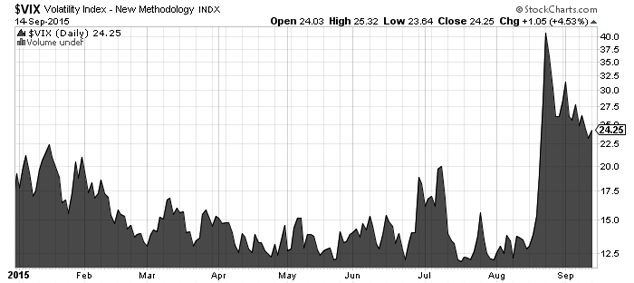

The retrenchment of globalisation means two things straight away. It probably means a lot more than that, of course. But for investors, there are two immediate things to factor in to your decision making. First, increased volatility. Second, capital flows out of emerging markets and into advanced ones. Check out the chart below.

The volatility index (VIX) made an appearance in the first issue of the London Investment Alert. But the key with the indicator is that it’s more of a lagging indicator than a leading indicator. Think of it like the Richter scale – it measures the magnitude of an earthquake; it doesn’t predict one.

For the VIX to be predictive you have to use it counterintuitively. The longer the VIX is ‘quiet’ the more you should be worried. As a measure of options activity on large stocks, the VIX is really a measure of how many people are hedging their risk in a bull market by buying put options. The quieter the VIX, the less activity in the options market.

If you aren’t hedging, you aren’t thinking

This, of course, is the whole purpose of a hedge fund. It’s not to outperform the market in a bull market, although that’s always a nice result. Typically, if you do outperform, it’s because you have one single position that hits it big. But the ‘hedge’ is in the title of the strategy for a reason.

A hedge fund outperforms in a bear market by losing you less money than the market. It does this, theoretically, by diversifying your portfolio. A tidy strategy to park your money in negatively correlated assets, or assets uncorrelated to the market, is the best way to ‘hedge’ your risk.

It doesn’t, by the way, mean your strategy is riskless. No strategy ever is. It just means you’re actively thinking about and managing your risk. That’s always a good idea. And on that note, it shows you that no matter what people say about China being the most capitalist country in the world, Chinese police still don’t understand risk.

In one of his ‘intelligence bulletins’ from the first issue of the London Investment Alert, Tim Price quoted a New York Times article in which Chinese police raided the offices of hedge funds in Beijing and Shanghai. The purpose? If you ask me, there’s only one reason for that sort of visit: ‘to strongly discourage’ rumour mongering and short selling, and intimidate fund managers into being bullish.

Short-selling is one way of hedging

By taking it out of the investor’s tool kit, you make the market less stable and more volatile. It’s convenient to think that all short-sellers are mean-spirited people who don’t deserve to profit. And it’s true that with naked short-selling – borrowing shares you don’t own to sell them for a profit – it’s hard to see any value being created.

If anything, short-selling itself is a signal that the market has made a pricing error yet to be translated through to a single security or an entire index. Yes, I know that is heresy to proponents of the ‘efficient market hypothesis’. But with so many distortions in the price of credit, how can you not expect distortions and errors in the price being paid for future earnings?

Think of short-selling, hedging, and put options activity as a kind of ‘compressional wave’. It’s a signal that gets sent out that not everyone detects. But it tells you something bigger is coming. A great article on the Cascadia fault-line in America’s Pacific Northwest described it this way (emphasis added is mine):

“Compressional waves are fast-moving, high-frequency waves, audible to dogs and certain other animals but experienced by humans only as a sudden jolt. They are not very harmful, but they are potentially very useful, since they travel fast enough to be detected by sensors thirty to ninety seconds ahead of other seismic waves. That is enough time for earthquake early-warning systems, such as those in use throughout Japan, to automatically perform a variety of lifesaving functions: shutting down railways and power plants, opening elevators and firehouse doors, alerting hospitals to halt surgeries, and triggering alarms so that the general public can take cover.”

Incidentally, the US Geological Survey reported that an earthquake measuring a magnitude of four on the Richter scale hit eastern Seattle on Saturday. It said the earthquake was located 12 miles underground. At that depth it was unlikely to do a lot of damage.

Still – spooky

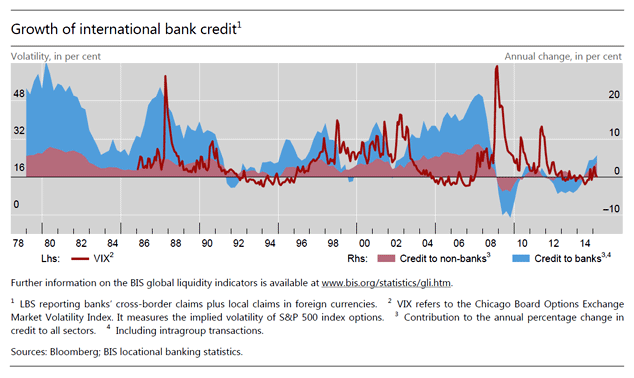

And still, you can see the point. There are some indicators in the global financial system flashing red. They indicate great stresses at key points. Capital flows are already reversing as those stresses give way to movement and conflict. Take the chart below from the latest quarterly report from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

The BIS has its own proprietary set of global liquidity indicators. It publishes those on a quarterly basis. At some levels, stock values are driven as much by liquidity as by perception of value (undervalued or overvalued, take your pick). The indicator above compares the VIX (left scale) to growth in international bank credit.

The chart is the bane of those who support quantitative easing (QE). It shows that the growth in central bank balance sheets has not lead to an increase in bank credit. This is both good news and bad news. It proves the points that banks are the main way low interest rates are transmitted into new credit. And the good news is that massive QE hasn’t resulted in hyperinflation in the real economy.

The bad news

If you’re the sort of person who believes you can manage the world’s economy with interest rates – is that low rates are not resulting in new bank lending and ‘growth’ for its own stake. At a global level, capital is flowing out of ‘growth’ markets and into ‘safe’ markets. Claudio Borio of the BIS put it this way in his remarks on the quarterly report [emphasis added is mine]:

“Since at least 2009, domestic vulnerabilities have developed in several EMEs [emerging market economies], including some of the largest, and to a lesser extent even in some advanced economies, notably commodity exporters. In particular, these countries have exhibited signs of a build-up of financial imbalances, in the form of outsize credit booms alongside strong increases in asset prices, especially property prices, supported by unusually easy global liquidity conditions. It is the coincidence of the reversal of these booms with external vulnerabilities that should be watched most closely. A holistic view is critical. We are not seeing isolated tremors, but the release of pressure that has gradually accumulated over the years along major fault lines.”

Note the use of earthquake terminology. Now, look for the compressional wave in London. Likely sources? Nine Elms. The property market in general. Gilts. More tomorrow.

Category: Geopolitics