“The Italian Horrorclown”.

That’s what Germany’s mainstream Der Spiegel newspaper called Italy’s Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini late last week. The picture to go along with the story wasn’t flattering either.

Meanwhile, Der Spiegel also found a Greek economist willing to say, “The Greeks have understood that the government cannot magically create money”.

He should’ve added the words “any more” to the end of the sentence. As the Greeks see it, the Germans are stopping them from magically creating money like they used to.

Devaluing the drachma was the go-to way out of their habitual mess. The same for Italy. But on the euro, they can’t devalue any more. The accountability and consequences this imposes are new and disconcerting.

According to the Greek economist, the Greeks have seen the error of their ways and become more German. Today, the Greek government returns to the markets to borrow. The biggest bailout in history worked. Congratulations to the EU, International Monetary Fund and the Germans.

Now, with Italy kicking up a fuss about their own budget, the Germans have a proof of concept when it comes to teaching the Italians the same lesson.

The only trouble is, Italy is rather bigger. And, I suspect, too proud to put up with the Greek treatment. The result will be different.

But today, we look into the German side of the argument first. Because that may be where the buck stops. Or the euro, in this case.

What I didn’t realise is just how justified German austerity-based beliefs will feel for someone who can remember the early 2000s.

And realising just how self-righteous Germans must be feeling about southern Europe has me very worried. It could well be that it’s the Germans who end up splintering the euro. In a very specific way.

How? The peculiar way that the Soviet Union’s monetary union ended. And when the Germans pull the plug indirectly, it’ll lead to the monetary system we got when the Currency Snake broke down in the 1970s.

In other words, all of this has happened before. So it’s not farfetched. In fact, I consider it unavoidable. The only question is how the end of the euro plays out.

Let’s look into the reasons why German patience is wearing thin and won’t extend through the next euro crisis. Which will begin in October if it hasn’t already begun with contagion from Turkey and the political drama over Genoa’s bridge collapse.

The first eurozone crisis played out in Germany, not Greece

In 2004, the European Commission ordered German state banks to pay a fine of more than €3 billion.

The argument was that, because many German state banks have state government guarantees, they’re effectively subsidised. They can borrow at artificially low rates thanks to the explicit government bailout. Like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in the US.

Under the EU’s rules, guaranteeing a bank provided it with an unfair advantage. So the banks had to pay fines equivalent to the value of the effective subsidies. Plus interest. (This is back when there still was some.)

Unable to continue without state government backing, the state bank in my birthplace eventually closed its doors in 2012. At one point, it had been Germany’s largest state-bank.

Only months later, German taxpayers were bailing out Greek banks under European Commission schemes…

As Hans-Werner Sinn put it in his book: “North Rhine-Westphalian taxpayers are not allowed to bail out their own state bank, but they may have to participate in bailing out banks in other euro countries.”

You can imagine how that went down in Germany.

Strangely enough, the Greeks saw their bailout as a simple matter of Germans rescuing German banks who had lent Greece money. They implied the bailout of Greece was a sleight of hand that didn’t actually benefit Greeks. That deeply angered Germans in several ways.

If the Germans had just wanted to bail out their German banks, they could’ve done so directly. And left the Greeks to their default and crisis. It would’ve been horrific for Greece. The government would’ve been unable to borrow and forced to balance its budget immediately.

But instead, German money went to Greece first, allowing it to continue borrowing and giving the country time to reform.

In return, the Greeks accused the Germans of being deceitful and self-interested…

The nature of the Greek backlash tells you how southern Europeans see the eurozone and Germany. As a cash cow that will rescue them from their own largess. And they’ve been right.

Even more remarkable is the fact that German households were asked to bail out the rest of Europe, despite being significantly less wealthy than households in other countries.

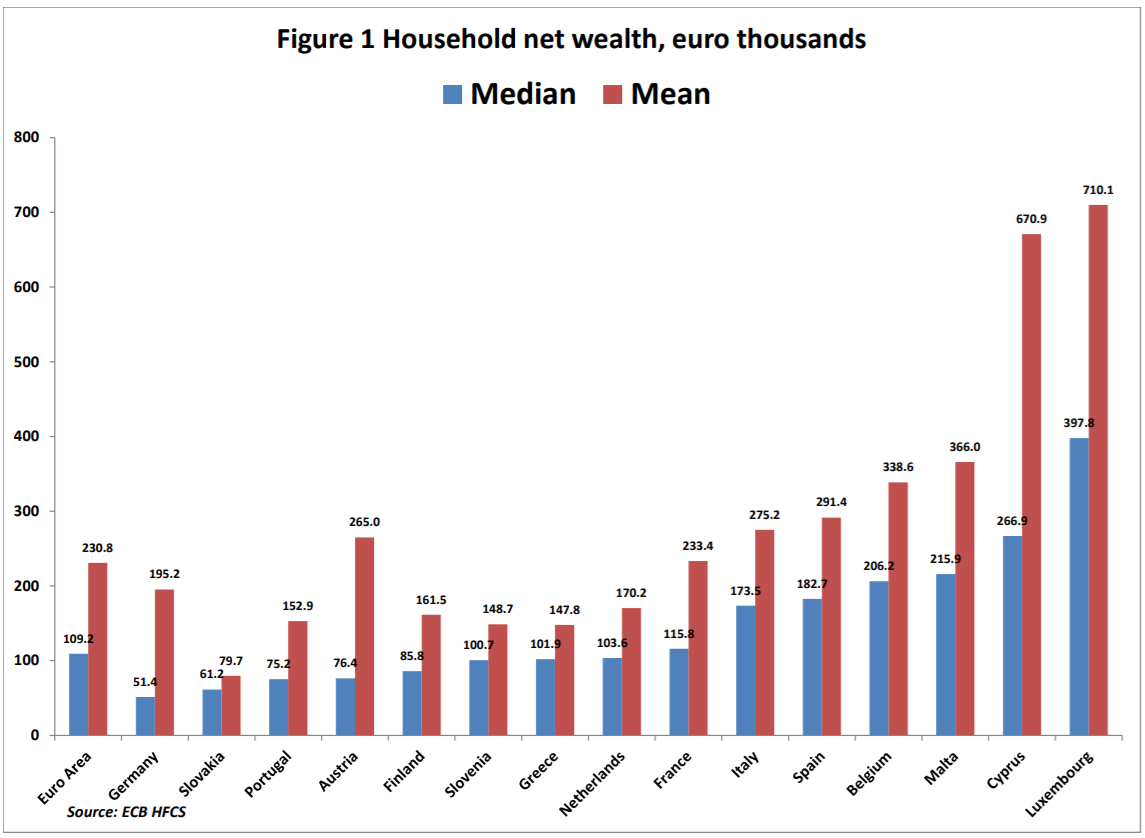

In 2012, Germans registered the lowest median household net wealth of the 15-euro area members for which data was available when the Peterson Institute compared them:

Germany, generally viewed as the richest country in Europe and the biggest resource for taxpayer bailout funds, in fact recorded the lowest median net household wealth in the 15 euro area members for which data is available at just €51,400. This is less than half the euro area average median household net wealth at €109,200.

Having the least wealthy voters in the eurozone bail out others? Hmmm…

The reason why German households are not as wealthy is fairly well understood. Homeownership rates are far lower in Germany, and the housing bubble of the 2000s never took hold there. That’s changing now, with a property boom underway in Germany thanks to the European Central Bank’s (ECB) monetary policy.

But having seen where housing bubbles left Ireland and Spain after their bubbles crashed, the Germans are not so happy about their own boom. And thanks to low homeownership rates, only the wealthy are benefitting.

So the Germans see the ECB’s extraordinary monetary policy as a risk, not a benefit. They see housing speculation booms as inherently doomed. Again, their own prudence is highlighted in comparison to southern Europe’s.

Meanwhile, the Target2 balances are surging. Germany is in effect lending vast amounts of money south, without a choice and without a hope of getting any of it back. The export boom is not enriching Germany, it is financing southern Europe with debt that won’t be repaid.

There’s one more event that you need to be aware of to understand the coming German reaction to the next euro crisis.

As the Germans see it, they lived through the austerity policies that southern Europe kicked up such a fuss about. Just a few years earlier. Germany was “the sick man of Europe,” and nobody cared.

I was living in Germany when the Hartz IV reforms were debated. These implemented the sort of austerity reforms that Germany demanded of Greece. The sort that must be made for a monetary union to function, because the currency devaluation option is thrown out.

If you take away the pressure valve of a floating currency, you have to reform your economy in a crisis. That means cutting wages and benefits, waiting out the recession until you become competitive again, and becoming more productive.

It also means implementing a lot of taxes to fix the budget. A popular song from back then was made by an impersonator of Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder. The lyrics featured a list of some of the huge amounts of taxes he introduced, going against his campaign pledge on day one of his government.

Sung to the tune of “The Ketchup Song”, the lyrics sung in Schroeder’s voice echo Greek complaints of 2012:

Yet all I want is your best: your money!

Dog tax, tobacco tax,

motor vehicle and environmental tax.

Did you really think there wouldn’t be more?Sales and beverage tax

to make a beer truly expensive,

but that is still not enough for me!

And the chorus:

I’m raising your taxes.

Elected is elected,

You can’t fire me now.

That’s really the cool thing about democracy.

As the Germans see it, they dealt with what Greece and Italy must, but in the early 2000s. Instead of the Troika, they had Gerhard Schroeder imposing austerity, taxes, welfare reform and labour reform.

There are some key differences, of course. At the time, inflation was running high in southern Europe. So the Germans didn’t have to lower prices to become competitive, they just had to wait for the rest of Europe to raise prices too much.

Germany also didn’t go on the same debt and spending binge before it became “the sick man of Europe”. So the correction was far smaller. But still slow, painful and drawn out.

The point is that German sentiment towards southern Europe has plenty of examples, logic and self-righteousness backing it. It isn’t some sort of baseless cultural phenomenon.

The trouble with this is what the Germans will do as a result.

I’m saving that for Zero Hour Alert subscribers this month. Boaz Shoshan is working on the best way to escape the problem. A solution that worked very well in the aftermath of Europe’s other failed currency unions.

But keep reading for what I will reveal here.

This time, it isn’t Greece

Within hours of the Genoa bridge collapse, each nation’s newspapers had their stereotypical reactions.

The Australian media blamed the mafia practice of mixing sand into cement.

The Germans compared their bridge inspection regulations to Italy’s.

The Americans reported their ratings agencies might downgrade Italy.

The UK media pointed out that “French bridges ‘at risk of collapse’” too.

And the Italians blamed austerity and EU budget constraints.

The EU fired back that they spend plenty on infrastructure. But Horroclown Salvini quickly pointed out that the money came from Italy and returned with terms and conditions attached. Not a good trade.

It was all very comical in the face of an extraordinary tragedy.

But the drama gives away the nature of the conflict. This is one of those rare occasions when both sides of an argument are perfectly correct. And so the thing to do is obvious, just unpalatable.

Italy can take back control of its infrastructure, spend without EU oversight and devalue its currency to gain competitiveness. Devalue as it did many times before, even after it had committed to fixed exchange rates. As it has many times before in Europe’s other failed monetary unions.

Germany can be rid of its implicit bailouts of southern Europe, unfair trade, wacky monetary policy and the Horrorclown. It can escape the blame games of southern Europe.

The unpalatable solution and resolution is to end the euro.

The only question is, who moves first. And how do they go about it.

Ending the euro would be the same solution that resolved the same problems for Europe’s other monetary unions in the past. And by studying the failure of Europe’s many monetary unions, going back to 1865, I’ve discovered invaluable information suggesting how the euro will die too.

The only trouble is, nobody can leave without a bang. A financial crisis of incredible proportions.

I believe the showdown is scheduled for October, when the Italian budget is negotiated with the EU. And the Italians see the Genoa bridge collapse as their trump card. It’ll justify an infrastructure spending spree that lays waste to EU rules.

Deputy PM Salvini said: “The Italian state must invest all the money needed to ensure the safety of our roads, railways, schools and hospitals, regardless of limits and mad European rules imposed on us.”

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard is worried that Salvini will take the opportunity to dissolve the coalition government if other parties push for compromise with the EU. He has gained enormously in polls since the election with anti-EU rhetoric.

The Germans will attempt to stand firm, for all the reasons we looked into above.

The Germans and the Italians are on a collision course. And neither side will flinch. The question is where that leaves us.

Zero Hour Alert subscribers will find out exactly how the Germans will scupper the euro (and escape most of the blame) in two weeks’ time.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: The End of Europe