Italy’s Target2 liabilities hit a new record in August. Then again in September, and November. And again in December.

Each time, it made the news. And each time most people who read the headline had no clue what it meant.

Well, Target2 is the reason Alan Greenspan expects the euro to fail. And in spectacular fashion. So perhaps you might want to know about it?

A team of our editors found themselves in a closed-door meeting with the world’s most powerful former central banker, Greenspan, about a year ago. There were no representatives of the mainstream press there.

Here’s what he said, with added emphasis.

There’s one thing that bothers me considerably, which nobody makes any mention of. There is in the European Central Bank a mechanism as it exists of necessity where the European Central Bank is made up of the central banks of the European, euro area and there’s a thing called Target2, do you know what Target2 is?

Target2 at this particular stage is turning out to be an extraordinary large transfer from Bundesbank to essentially Italy and Spain, and most recently the European Central Bank. That means the Bundesbank is lending money to the European Central Bank and the question is – it’s big numbers. We’re talking 7,800 billion euro.

Something is going to happen there. My view is it’s either going to be Greece – it conceivably could be Italy. […] but it is extraordinary what is going on in this system while the total assets of [the] European Central Bank continue to go straight up. What would happen if there was a default of the euro?

In the United States, if there were a default on the dollar the US Treasury could always [step in]. For example, if the federal reserve went into default the US Treasury would bail it out but what [European countries] do? There is no comparable vehicle to help the system.

I’m very worried. Mario Draghi, whom I know and he’s a very good guy, is just talking like we’ll do whatever is required. Well at some point somebody’s going to say, “I don’t want to accept euros.”

From where our editors were sitting, it sounded like Greenspan believes the next major financial crisis will be triggered by either Greece or Italy and will result in the total destruction of the euro as a major currency.

With Greece continuing to rely on bailouts from the Troika and even more debt forgiveness, and Italy’s bad debt problem far from resolved, Greenspan seems to be on to something. But what is the Target2 that he’s so worried about?

Target2 exposes the fatal flaw of the eurozone

The eurozone has a very complex monetary and banking system. Because it wasn’t designed from the ground up, but evolved from a long list of countries being shoved in together, largely against the will of their people, the system is a bit odd.

It also has a fatal flaw, which we’ll get to in a moment. Each time this flaw leads to a problem, the europhiles add a layer of complexity to cover up the symptoms. But failing to address the underlying cause just creates new problems. Problems like Target2.

Target2 is the system by which the various European central banks, the European Central Bank (ECB) and Europe’s commercial banks interact. They settle large transfers of funds using the Target2 system.

The key players are the German Bundesbank, the French Banque de France and Italy’s Banca d’Italia. Nineteen other central banks are involved, plus four from outside the eurozone. The Bank of England doesn’t participate.

What can be wrong with a payment system? Greenspan mentioned it above. The transfer of funds seems to be steadily going one way. Out of German hands and into southern European.

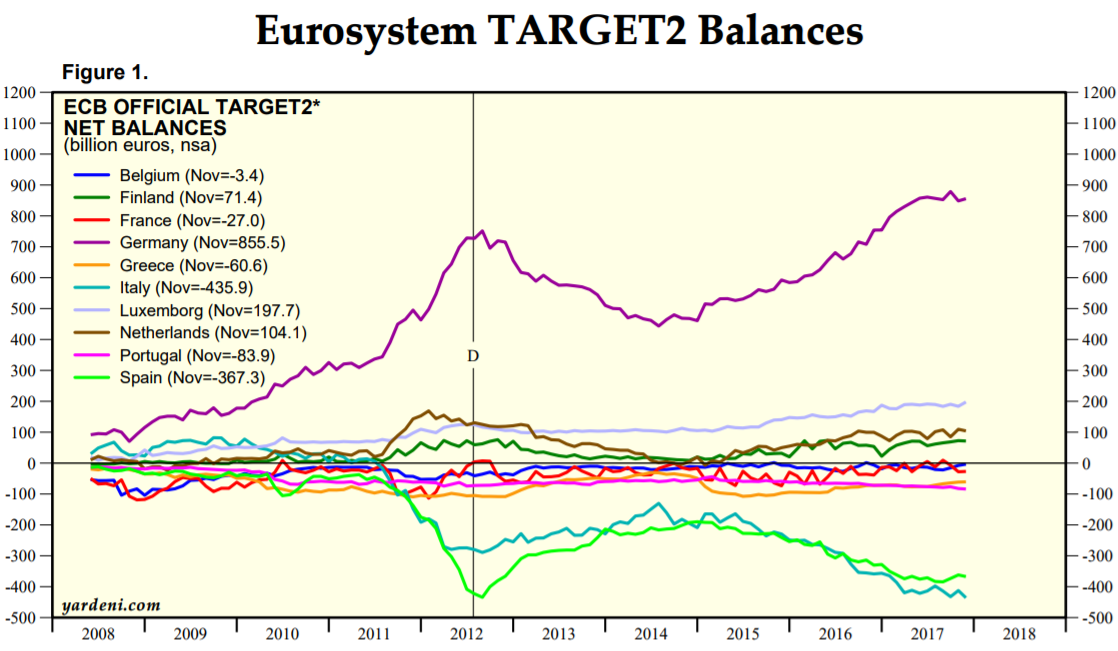

This chart from Yardeni Research shows how Germany, in purple, is financing Spain and Italy, in green and teal:

The Germans see this as an enormous risk. They could be the ones left empty handed when southern Europe defaults.

The southern Europeans resent the German dominated credit market. German lenders decide who gets to borrow and who doesn’t.

The Target2 system’s imbalances expose the eurozone as the monetary version of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. They show who is paying to keep the eurozone afloat and who is living off other people’s money. And the figures far outweigh any contributions to the EU budget or other transfers.

But the system has to function to keep the euro system alive. So if it sputters or fails completely, that would have enormous consequences for Germany too. Especially given its export-oriented economy sends goods to southern Europe.

If you think all this is a bit obscure, you’re simply wrong. The Target2 imbalance already triggered legal challenges and political campaigns in Germany. An extraordinarily popular book explained how the Target2 “trap” poses an immense risk to German “money and our children”. And the Bundesbank took the ideas seriously enough to try and refute them.

Europe’s institutions and leaders ensure us that the system does not pose any risk because of its features. But that’s nonsense because it’s the failure of the system that everyone is worried about.

But how did this dreadful imbalance develop in the first place?

The fatal flaw of the eurozone

Even if central bankers’ motivations were as pure as Greenspan suggested, and their wisdom as infinite as they project, don’t forget that monetary policy is responsible for the financial crisis of 2008.

In the US, the Federal Reserve and Greenspan copped some of the criticism they deserved. Many commentators now agree that interest rates were kept too low for too long in the 2000s, inflating the housing bubble.

But in Europe, the ECB’s one-size-fits-all monetary policy was never blamed for the housing bubbles in Ireland and Spain. Those countries should’ve had higher interest rates when their property markets boomed. But Germany’s economy was the “sick man of Europe” at the time, requiring low interest rates. This financed the housing bubble’s excesses in the peripheral countries.

It’s hard to deny this given the precise opposite has happened since. Germany is now benefiting from interest rates that are far too low for its booming economy. But the ECB can’t raise rates on the struggling Italians and Greeks.

This is the fatal flaw of the eurozone. One monetary policy for all those different countries means the wrong interest rate applies everywhere.

Some countries are getting money too cheaply, growing housing and debt bubbles. While for others, the same monetary policy is too tight. Over time, this is leading to enormous anti-euro sentiment and economic instability. Not a good combination.

How does all this break down? There are two possible ways.

The first is politics. Political parties that are eurosceptic and anti-euro could be elected to parliaments around Europe, forcing change. That’s process is well underway. The Italian elections in a month will be the key.

But my friend Charlie Morris is expecting something a little different. He thinks a change in the tides of money is about to upset the balance in the world’s most important financial markets. And if he’s right, it’ll be enough to sink the EU and the euro as we know it.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Related Articles:

Category: The End of Europe