Do you remember when ratings agencies ruled financial markets? A 2010 BBC opinion piece started with, “Is there any more powerful and feared institution in Europe (or the world) than Standard & Poors?”

Yikes.

Today I explain why I think it’s time to prepare yourselves for a comeback of the ratings agencies. And this time, it’s not Greece that’ll be fighting it out with the economists.

But first, let’s take a step back to set the scene. Because it turns out that the answer is yes, there is a more powerful institution in Europe.

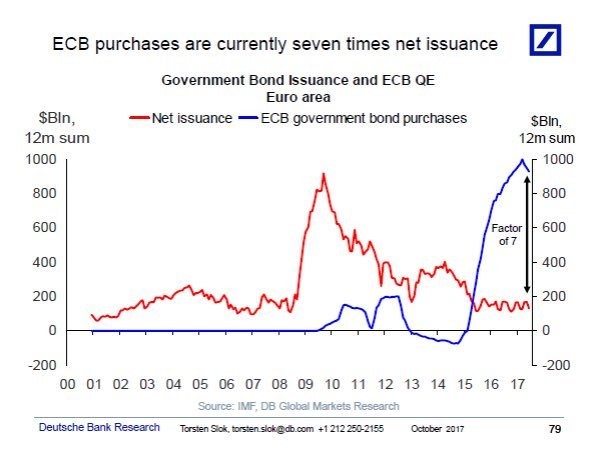

This chart from Daniel Lacalle’s Twitter account is a real humdinger. It shows that European Central Bank (ECB) purchases of government bonds were running at a pace that was seven times the net amount of European government bonds being issued. That means the ECB was financing European government deficits seven times over.

Source: Deutsche Bank

Source: Deutsche Bank

In the understatement of the century, Joost Beaumont from ABN Amro told the Financial Times last year that, “There are not many debt markets that are not distorted in the euro area.”

But notice how he is referring to debt markets generally, not just sovereign debt. The same Financial Times article went on to detail the extent of ECB interference.

Covered bonds – 27% of the entire covered bonds market is owned by the ECB.

Government bonds — €1.34tn.

Corporate bonds — €61bn.

Asset-backed securities, which include mortgages, credit card debt, car loans and other consumer credit — €23bn.

How anyone can think European bond yields reflect any sort risk or reality is beyond me.

Unless of course ECB quantitative easing (QE) policies are coming to an end. Which they are supposed to later this year. That’s when we’ll find out what the markets really think about European debt.

Assuming the truth isn’t too painful to uncover.

How long can the ECB rescue Europe?

The ECB isn’t supposed to finance government spending. It just happens to do so “by mistake” when it’s implementing monetary policy. Whoops.

But what about the rules designed to stop this?

The ECB’s rules are like the Pirates Code in the film Pirates of the Caribbean: “The code is more what you’d call ‘guidelines’ than actual rules. Welcome aboard the Black Pearl!“ Here are some examples:

In May 2010, the ECB changed its collateral rules to allow for downgraded Greek bonds, having just done the same temporarily the month before.

In December 2016, German bond prices rose so ridiculously far that yields went deeply into negative territory. The ECB was forced to change its rules to be allowed to buy them.

Confusion reigned about the ECB’s corporate bond purchase programme in October 2016 when the central bank found itself owning junk bonds after the debt rating downgrade of a German potash producer. The ECB just changed the rules.

But the ECB hasn’t just been busy humiliating itself with its shifty “rules”. It uses the flexibility to humiliate others too. In 2015, the central bank suspended the waiver of the rules on Greek bonds until the Greek government agreed to submit to the Troika’s austerity plan. Greek banks were unable to access ECB funding using those Greek bonds until their government gave in.

The same battle between the nation state’s rights over fiscal policy and the central bank’s obligations is going to play out again with Italy in coming months.

My point being that the budget battle with the EU, which I’ve been writing so much about, might be a sideshow. An important sideshow given it determines whether the ECB will act or not. But a sideshow nonetheless.

The real question is what the ECB will do. Because it is the only EU institution which has the power to implement “whatever it takes” to rescue European bonds. And it’s not democratically accountable either.

Before we get to how ratings agencies will make a comeback in the battle between Italy, the EU, and the ECB, let’s remember the first European sovereign debt crisis as a wider picture. You need to know where everyone stands before the battle begins.

The rules of the game and the starting point

Under what’s known as the “first-best rule”, at least one ratings agency must rate a sovereign bond as investment grade in order for the ECB to buy it. Under the most commonly known QE programme, anyway.

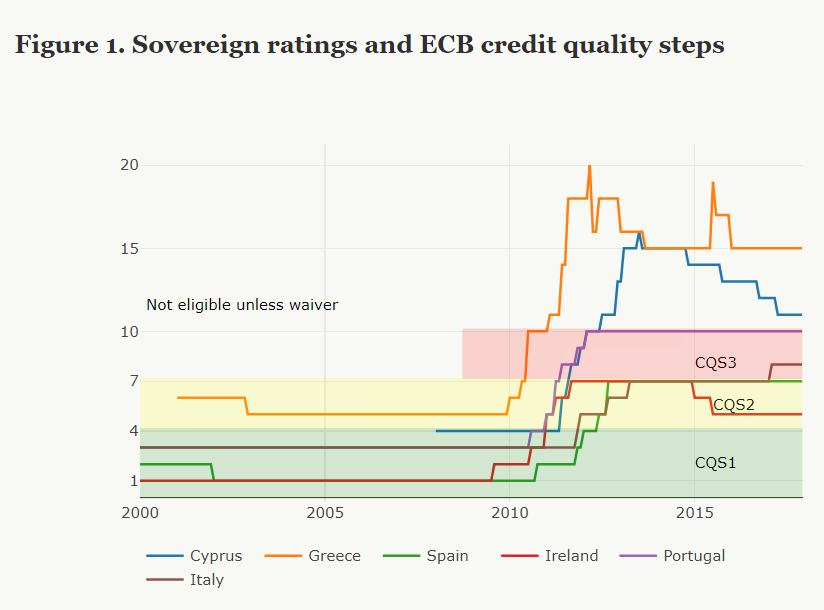

The think tank Brugel drew up this chart, which shows how various nations skirted the ECB rules since 2010. The y-axis is a sort of amalgamation of the ratings agencies. Above 10 and you’re out of the ECB’s rescue remit, unless you get a waiver.

Notice just how close Italy and Portugal got. And for how long.

In fact, an obscure Canadian ratings agency called DBRS was the only agency which kept Italy out of trouble back in 2013 with an A rating. The three well-known agencies all had Italy rated lower.

The special thing about needing a waiver is that it brings the ECB’s judgement into play. As Greece did, to get a waiver, a nation must play nice with the Troika of the International Monetary Fund, ECB and EU. Otherwise the ECB shuts out the country’s sovereign bonds, and thereby its banking system.

All this worked so well in 2012 that it was codified by the EU into a new set of programmes with new “rules”.

OMG, it’s OMT

The key programme with which the ECB could rescue Italy has never been used before. It’s called Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT). It’s the programme that the Germans legally challenged. And lost. Sort of.

The OMT rules require a nation to be in the fiscal charge of the EU under a pair of other bailout and austerity programmes before the ECB can rescue them.

Back in May, Reuters summarised how the outgoing ECB vice-president explained it: “ECB’s Constancio tells Italy: read the rules on central bank support” because “any intervention by the European Central Bank to help Italy in the event of liquidity problems must meet the bank’s mandate and ‘certain conditions’”.

The conditions involve the very austerity programmes that ruined Greece.

You might notice that this leaves us right back where we started. The face-off with the EU is crucial again, not just in terms of EU rules, but in terms of what the ECB is allowed to do under OMT as well. The ECB bailout that Italian politicians are banking on in the media requires them to implement austerity too.

During the height of the sovereign debt crisis, and in May, the Italian politicians were furious with how the EU used Italy’s government bond yields to pressure Italian politicians into accepting their proposals. This is in fact their modus operandi under the new law too though. Without EU approval under fiscal rescue and austerity programmes, the Italians won’t get an ECB bailout.

Renowned economists Olivier Blanchard and Jeromin Zettelmeyer explained in a blog post at the Peterson Institute for International Economics that Italian politics isn’t exactly promising a budget compromise. The fiscal plan previous governments had agreed upon with the EU is the “the opposite of what Italy’s new government has promised” voters. So, “Unless the government were to change course, it would be forced to exit the euro, even if this is not the current plan.”

But one voice in Italian politics says otherwise. According to the economy minister, Italy is going to propose a compromise budget that the EU will approve. While meeting all spending promises made to voters too…

Impossible you might say? Well, showing he has a sense of humour, the minister also said he is looking to “confirm the commitment to proceed along the path to reduce Italian debt.” That’s a “firm possibility of a definite maybe,” if ever I saw one.

Alessandro Polli, an economic statistics researcher with Rome’s La Sapienza University, told China’s Xinhua newspaper that none of this matters anyway.

“The actual rating wasn’t lowered, and anyone who follows Italy closely will know that a lowered outlook for the future should be taken with a grain of salt because so much of the political situation can change so quickly,”

Until the actual budget is proposed, you can posture and promise all you like.

With the EU and the ECB’s OMT set for a political battle, attention returns to the ratings agencies.

Return of the ratings agencies

Because the OMT programme is hampered by the EU’s austerity programmes, the ratings agencies become relevant again. The old rule about what the ECB can buy applies now that the EU has codified the OMT rules. And the ratings agencies are the keepers of that old rule under the first-best policy.

In fact, the ratings agency panic is set to return in a matter of weeks. It was supposed to return last month, but two ratings agencies delayed their verdict. They’re waiting for “better visibility” on the Italian budget.

On Friday, the third agency Fitch downgraded the outlook on Italian debt to “negative” from “stable”, which isn’t quite an official downgrade of the actual credit rating. But it’s a warning of what’s to come.

If the Italians really do propose the budget they’ve promised voters, and the ratings agencies react with downgrades as they’re supposed to, the Italian bond market will return to turmoil. Investors will begin to worry that another wave of downgrades will leave the ECB powerless to rescue Italian bonds unless the Italian government compromises.

Comments like these from 2014 on CNBC are simply not going to cut it in 2018: “Italy has rejected Standard and Poor’s (S&P) downgrade of the country’s sovereign credit rating to just above junk level, saying the government doesn’t share the same concerns as the international credit rating agency.”

In 2011, Italian police raided the Milan offices of Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s while investigating the companies for “respecting regulations”.

Does anyone want to bet on a repeat?

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: The End of Europe