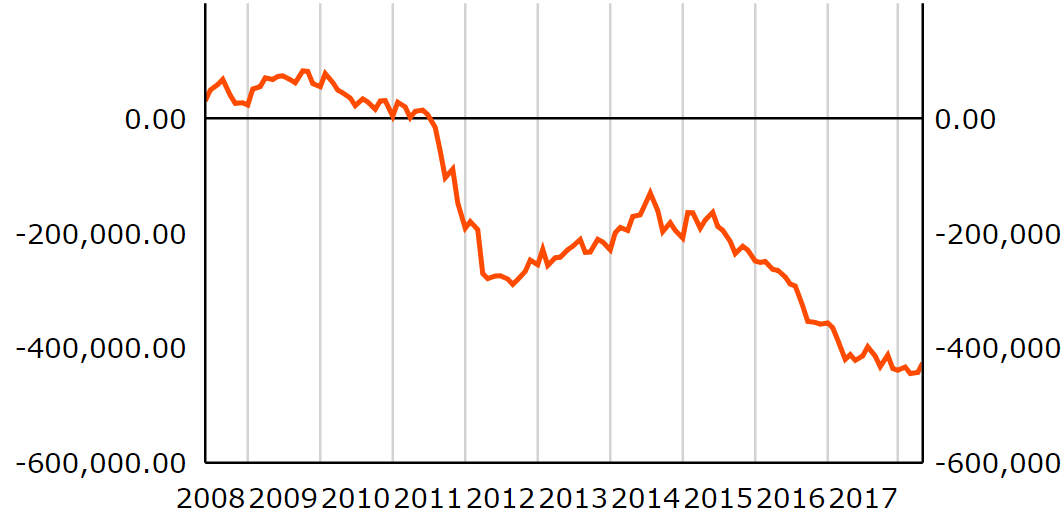

Italy’s financial crisis didn’t return with a bang on Friday as I expected. And Italy’s Target2 liabilities didn’t spike in April either. They more or less held steady:

Italy Target2 balances

Source: European Central Bank (ECB)

Italian bonds staged a decent comeback towards the end of the week. Is the second European sovereign debt crisis over already? Can you safely ignore my warning that the biggest debt default in history is coming this year?

What’s really going on is rather complex. Because the EU’s financial plumbing is complex. The idea of the complexity is to cover up simple truths. Because if you grasp them, it’s easy to understand why the euro is doomed and Italy is on the path to escape through default.

You can expect matters to get out of hand when the Target2 data for the month of May is released in the beginning of July. That information will show how investors panicked as the Italian government formed. It’ll expose…

Capital flight in a monetary union

Let’s dig into one aspect of Target2 to illustrate its importance.

Philipp Bagus of the Mises Institute, who wrote the excellent book Tragedy of the Euro, explains one feature of Target2: “Imagine a Greek entrepreneur purchasing a truck produced in Germany”. Euros flow from the Greek banking system to the German one. But that’s not all that happens: “On the level of central banks, the Bundesbank receives a credit against the ECB while the Greek National Bank gets a debit.”

In this case, the aim of the Target2 game is to keep the amount of money sloshing around Greece and Germany the same, despite the cross-border flow of money in the private system. Target2 is the system that makes this happen. It sends money back south from Germany to Greece and creates an IOU in the Target2 system for Greece, while Germany gets an asset of sorts.

Without Target2, there would be a shortage of money in Greece and a surplus in Germany from the transaction above and in general given the trade flows of those two countries.

The problem is what this system implicitly results in. In the example above, the Greek consumption of German goods was enabled by a corresponding Target2 transaction where Germany effectively finances the Greek consumption by sending money back south.

“Target2 has become a giant credit card for Eurozone members that import more than they export to other members” writes economist David Blake in City A.M. It’s an interest-free credit card without any repayment terms and no limits.

The long-term implications of Target2 are similar to those of the euro itself. Imbalances build up that have no self-correcting tendency to them.

Usually, exchange rates move in a way that encourage a rebalancing of trade over time. But Europe doesn’t have exchange rates inside the union.

Usually, Greeks would struggle to borrow money to buy more and more German trucks indefinitely. But under Target2, there are no costs or consequences from doing so on a vast scale. The economies do not rebalance their trade flows because the money just flows back into their country automatically via Target2.

But that doesn’t constitute the capital flight I mentioned above. It just shows how the euro system makes imbalances worse over time. And Italy is hardly a trade basket case.

The thing is, Target2 doesn’t just handle trade flows. Money can flee a country for reasons other than trade. Such as the capital flight in 2011 and 2012 according to ABN Amro senior economist Aline Schuiling:

Target balances soared during the years of the eurozone financial crisis in 2011-2012. This resulted from funding tensions in the banking sectors of some countries in the periphery (Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece and Ireland).

During this period, private money no longer flowed into the peripheral countries in quantities sufficient to compensate for their payment outflows.

Their banks suffered from funding tensions.

In order to prevent a banking crisis the ECB stepped in, accommodating the banks’ liquidity needs, by issuing three-year LTROs with full allotment and by lowering the collateral requirements in the ECB’s regular open market operations.

Thus the shortage in private flows into the periphery was settled in central bank money which resulted in their respective NCBs displaying, in cumulative terms, liabilities in Target.

So if Target2 liabilities are surging, it suggests capital flight within the eurozone.

That’s what I’d expected for the April Target2 figures as Italians reacted to the election in March and sent their money out of the Italian banking system. But perhaps it’ll take till May for the carnage to be revealed.

In the meantime, it’s worth noting just how mainstream the issue of watching Target2 balances has become.

In an article on City A.M., economist David Blake described Target2 as a “silent bailout system that keeps the euro afloat. Europe’s political elite know this – they just don’t want the rest of us finding out.” He also told the House of Commons International Trade Select Committee:

“However, the evidence presented in the report indicates clearly that Target2 has become a silent bailout system that keeps the euro afloat, but in doing so is also keeping key Eurozone economies in permanent recession.”

[…]

“Surplus regions need to recycle the surpluses back to deficit regions via transfers to keep the Eurozone economies in balance. But the largest surplus country – Germany – refuses formally to accept that the EU is a ‘transfer union’. However, deficit countries including the “largest of these – Italy – is using Target2 for this purpose.

“Further, the size of the deficits being built up is causing citizens in deficit countries to lose confidence in their banking systems and they are transferring funds to banks in surplus countries. Target2 is also being used to facilitate this capital flight. The result is that the Eurozone economies – particularly those of the southern member states – are stuck in a Japanese-style deflation trap.”

“Target2 is clearly not a viable long-term solution to systemic Eurozone trade imbalances and weakening national banking systems. There are only two realistic outcomes. The first is full fiscal and political union – which has long been the objective of Europe’s political establishment, but is not supported by the majority of Europe’s peoples. The second is that the Eurozone breaks up.”

That’s an excellent summary given in a political arena. The cat is out of the bag on Target2. And if it spikes in May as Italians sent their money north, it’ll reignite the worst of the European sovereign debt crisis.

Why Italy will eventually leave the euro and default

What’s the potential fallout of the euro system’s collapse? Nobody is entirely sure how it could even play out.

Under the ECB’s rules, the nations in the ECB system have to bear any losses of that system in proportion to their size (the so-called capital key). That means Germany may be owed close to a trillion euros under Target2, but if a country like Italy defaults on the system, every other country has to refund the ECB too.

Philipp Bagus puts it like this: “The ECB, thereby, has become a hedge fund betting on the survival of the euro.” Except the hedge fund’s investors can lose far more than what they put in.

ABN Amro’s Schuiling explains that, “Should the euro break up completely, creditor central banks hold a claim against a system that will cease to exist. Therefore, it is very questionable what will happen with these claims.”

Totally off the rails is the ECB president Mario Draghi. In a letter responding to MEPs, he explained that a country could leave the euro, but it would have to settle its debts with the ECB first.

This makes no sense. It’s like telling a country which is going off the gold standard because it doesn’t have enough gold that it must settle its debts in gold before it can leave. The whole point is that it doesn’t have the gold!

Where does all this leave the Italian crisis? The whole point of my report predicting a crisis in Italy is that politics will eventually make a predictable choice if you understand the underlying economics.

A research note from JP Morgan pointed out that the benefits of the ECB’s rescue of Italy’s bonds has primarily gone to foreign banks. Their holdings of Italian debt fell by half as the ECB bought them up under quantitative easing.

This means that a default on foreigners’ holdings of Italian bonds wouldn’t really help Italy much – it’d decrease debt-to-GDP by about 15%. A default on the ECB system, which has soaked up a huge portion of Italian government bonds, and is on the hook for the Target2 liabilities, is a much more effective way of cutting Italy’s debt.

It just also implies leaving the euro…

Britain’s stake in the euro crisis

David Blake also explained to the House of Commons International Trade Select Committee what Britain stands to lose.

First up, our government has contributed huge sums of money to EU and International Monetary Fund bailout efforts. Those would be wasted if the euro crisis returns.

But it’s the UK banking system that’s fascinating. At first, it appears we have little exposure to Italy and its banks. But that’s naïve. Our banks are so-called superspreaders. They’re exposed to any and every financial panic via contagion.

Here’s how Blake put it:

UK banks have made significant loans to both Irish and French banks, and the French banks, in turn, have made substantial loans to Italian and Spanish banks. So if any Italian and Spanish banks fail, this could have a negative impact on UK banks, not least by restricting their ability to raise finance in euros and other major currencies. There would also be problems if a Eurozone-headquartered bank, which did significant business in London, got into difficulties.

The spike in interest rates and funding costs would of course be passed on to our economy too.

If you think Brexit is going to save us from the collapse of the EU, you’re dreaming.

It’s time to understand Italy’s coming default, and protect yourself from the fallout.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: The End of Europe