How do currency unions die?

That’s the question I’m asking myself this week, as Nickolai Hubble prepares to publish his next big prediction about the slow-motion collapse of the euro financial system.

The short answer is: be very, very careful this autumn. More on that later in the week.

In the meantime, Nick and I have been discussing the mechanics of how such a major currency such as the euro could cease to exist – or cease to exist in its current form, anyway. We’ve been busy looking at the disintegration of other monetary systems for clues.

Right now, all roads lead back to a “backdoor” euro banking system. It’s called the Target2 balance system. It’s unlikely the man on the street will ever hear about it… or understand it.

But then, most people didn’t hear the term “subprime” until the banks had gone to the wall in 2008, did they?

That’s not a flippant comment. Target2 is serious. It both explains and predicts crisis in Europe. Today I’m going to show you why – and what it’s telling us today

A little bit of backstory before we get into the detail. It was Alan Greenspan – former Federal Reserve chair – that highlighted the importance of the Target2 system to me to begin with. It was part of a private meeting with Greenspan at Bill Bonner’s offices in Baltimore.

The whole meeting was an eye-opener (if I remember rightly, Greenspan described democracy as a system by which 51% of the population can “annihilate” the other 49%).

But it was his Target2 comments that really stood out. The short version is, Target2 is a great predictor of crisis, it’s a massive source of tension in Europe and no one really understands how to fix it.

If money moves from Italy to Germany – from one banking system to another ahead of a crisis – it doesn’t involve buying or selling euros at all.

The money just jumps from one place to another… like someone earning money in London and saving it in a bank in Leeds. From the outside, nothing shows up as having crossed any borders.

But – to state the obvious – Italy and Germany are not London and Leeds. They’re not in the same country. They don’t have the same banking system or economy. They just share a currency.

So when money floods out of Italy in fear of a crisis and ends up in a German bank… it’s bad news. That cash has drained out of the Italian economy and leaked into Germany.

It’s another great example of the built-in imbalances that’ll break the eurozone in the end.

But here’s the thing. The European Central Bank (ECB) can’t just let money flood out of one country and into another for good. It has to “correct” the imbalance to avoid a currency shortage. So it secretly funnels money back via the Target2 system.

So money flees Italy for Germany via the banking system. And the ECB funnels the same amount of cash back to Italy via its secretive Target2 system. The problem is the Target2 transfer is borrowed money – a form of debt. A hidden debt between European nations that puts even more strain on the euro.

All Germany gets is a claim in the Target2 system. No one knows how these claims will be settled.

This doesn’t just happen in times of crisis. It’s also a trade tension. If Germany exports goods to Italy (or anywhere within the eurozone), euros flow from Italy to Germany in return.

The problem? That cash has to be funnelled back to Italy and replaced with a Target2 claim.

As Nick pointed out to me last weekend, this means the benefits of exporting across the eurozone are – at a national level – fudged. Here’s how he put it to me:

Under Bretton Woods, countries with export booms accumulated gold. That was their “reward” for being so productive. It also forced the persistent importers to eventually devalue their currency against gold (the pressure valve). When Charles de Gaulle sent French submarines to pick up US gold, it signalled the beginning of the end for Bretton Woods and the US peg to gold.

Under the system that followed, a country with an export boom accumulates foreign assets as their reward. The Japanese bought Australian and London property with all the dollars and pounds they got in return for stuff labelled “made in Japan”.

But under Target2, the reward for exporting is a fudge. The Germans are accumulating huge Target2 claims on other eurozone countries instead of gold or foreign assets.

This isn’t worth bugger all, because you can’t sell it or call it in. Only a reversal of Germany’s trade balance would allow the money to flow back again. That won’t happen because there is no pressure valve allowing southern European countries to escape this state of affairs. In fact, the replenishment of money in their economies under Target2 prevents this rebalancing.

So the German baby boomers will have worked hard for a false asset they can’t sell… unless they do the equivalent of de Gaulle’s submarines, call in the Target2 debts and leave the eurozone. Balances would get settled, like with gold under Bretton Woods. Not that the Italians could pay.

I think this is what the outrage in Germany was about. It hasn’t got any wealth to show for its export boom. Just a Target2 claim. Which nobody will ever pay.

The point is, it’s easy to focus on southern European nations’ huge debts, slow growth and knock-on social/political problems. But behind the scenes, in a banking system no one really understands, we’re seeing all kinds of warning signs. The higher imbalances between euro nations via the Target2 system get, the worse those problems become.

That’s because – as I’ve pointed out before – the entire system doesn’t have a release valve. Exports build up imbalances. Capital flight builds them too.

And here’s the thing. So far, when debts within this back-door banking system spike… it’s a sure-fire predictor of crisis.

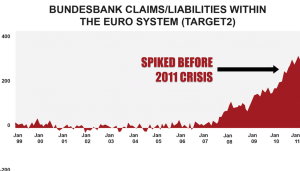

Take a look at this chart. It shows the lead-up to the 2011 European debt crisis. The spike in the chart represents a sudden flood of cash away from Greece, Ireland and Spain (all of which were on the brink of collapse) and into “safe” places like Germany.

Money flooded out of the southern nations, and triggered a crisis in those nations that smashed markets all over the world into bear market territory.

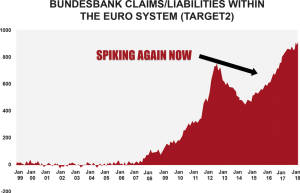

Today, history is repeating itself. But this time, it isn’t Greece that’s in trouble. It’s Italy. Take a look at Target2 balances right now.

Money on the ground is – once again – flooding out of the southern European nations and into Germany.

Italy’s Target2 liabilities hit a new record in August 2017. Then again in September, and November.

And again in December.

And once more in February 2018. And May.

Worried yet? You should be. Target2 might feel obscure and technical. But it could just be flashing a red alert. Understand the signs early enough and you’ll see what’s coming…

Best,

Nick O’Connor

Publisher, Southbank Investment Research

Category: The End of Europe