Those who don’t learn from history are doomed to start a currency union in Europe. That’s the key message from today’s Capital & Conflict.

It’s not a particularly stark revelation. You’ve been watching the eurozone fail since before it existed. The Currency Snake and the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) both failed.

Luckily Britain was among the failures. Otherwise we might’ve been stuck in the eurozone now…

Then came the European sovereign debt crisis and the European Central Bank’s (ECB) extraordinary monetary policy. A system that violates its own rules to survive is deeply flawed.

What you need to realise is that the failure of European monetary unions is nothing new. In fact, monetary unions around the world all have the same fate.

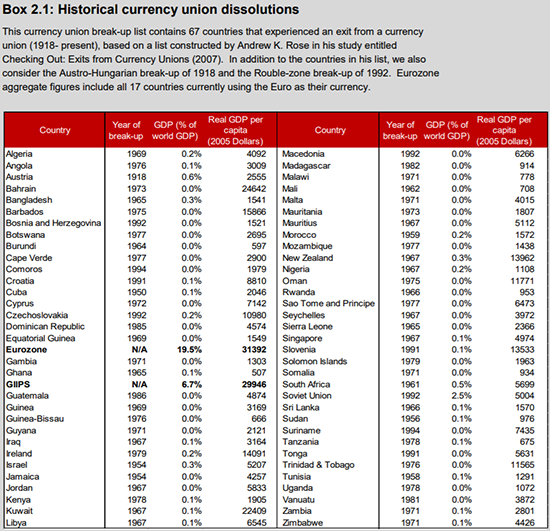

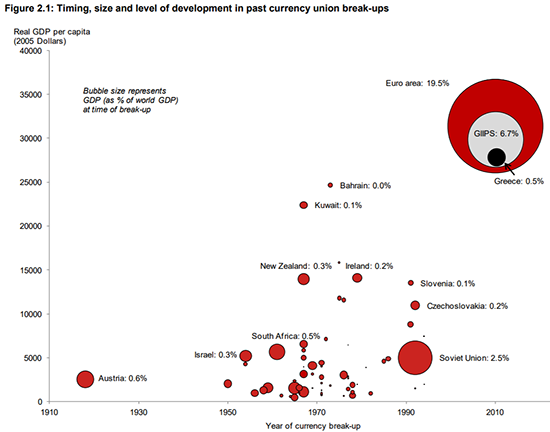

Jens Nordvig is about as accomplished a researcher, investment banker and writer as you can be. His report on “Rethinking the European Monetary Union” takes a look at past monetary unions. Here’s a list of 67 that failed last century alone. And a plot of their size and timing is included below too.

The euro area is included for illustrative purposes only – it hasn’t failed yet… at the time of writing this.

Nordvig only goes back to 1910. He missed a much older currency union called the Latin Monetary Union (LMU). France, Belgium, Italy, and Switzerland were the founding members in 1865. That’s a very big chunk of global GDP at the time.

What’s striking is how the same problems plagued the monetary unions of the past. The same culprits pop up. The same flaws are inherent. And the same abuses take hold shortly before failure.

Researchers wrote of the LMU in the Review of Development Finance that, “Throughout our results, it is clear that Italy’s volatile economic conditions and policies distinguish it from other countries, in spite of its membership of the LMU since its inception.”

Sound familiar?

Another issue for the LMU was that countries devalued their common currencies by debasing the gold and silver contents. The coins were supposed to be interchangeable, but had completely different precious metals content. The purer ones were swapped out, horded and melted down. The impure currencies circulated more widely.

In the story of the LMU, Italy broke ranks in this way first:

Less than a few months after ratification of the treaty, Italy suspended the convertibility of her banknotes into metal coins and put into circulation huge numbers of small denomination banknotes. Italy’s small silver coins, in turn, flowed into France, Belgium, and other neighboring economies.

You’ll never guess who was next:

Greece’s admission to the LMU was associated with a similar problem. To avoid a massive flood of small Greek coins, Greece agreed that all coins would be produced at the Paris Mint and shipped directly to Greece. However, small Greek silver coins were found circulating in Paris within weeks after the agreement was put in force.

Over in the Soviet Union, it was much the same. The satellite nations were subject to Russian monetary rule in the “rouble zone”. But they were able to take advantage of the shared currency by “exporting their inflation”.

In a monetary union, if one member creates a disproportionate amount of money, that nation gets the benefit while the entire monetary union shares the inflationary burden. The Nash Equilibrium gives you an inflationary mess, with each nation pushing the limits.

Today, we have the ECB buying disproportionate amounts of Greek and Italian sovereign debt.

The breakup of the Soviet Union’s rouble zone has other interesting lessons. The rouble zone featured something called Transfer Roubles (TR). They’re the Soviet version of the eurozone’s Target2.

In fact, the think tank Bruegel’s explanation of the Soviet TR reads like an explanation of eurozone’s T2:

According to the CMEA’s Complex Program of Socialist Economic Integration approved in 1971, the TR was to be also used for multilateral settlement purposes, i.e. trade surplus of country A against country B could be used for imports from country C.

In short, the TR was only used as an accounting unit to determine net balances in bilateral barter transactions registered on special accounts in the International Bank of Economic Cooperation in Moscow (a CMEA institution). A deficit in one year was to be repaid by surpluses in subsequent years, and took the form of a technical credit in the meantime.

The TR “was not a real currency” in the sense that you couldn’t spend it or exchange it for spendable money.

The problem here is that trade involves the exchange of things of real value. If all you get in returns is an accounting entry, this robs you of something of value. That’s what I wrote about on Monday regarding Germany’s Target2 imbalances.

The other inherent problem with this, in both the eurozone and rouble zone, is that it prevents the natural self-correction of trade imbalances. In fact, it preserves those imbalances.

Which is an even deeper problem, because the only way you can get value out of your Target2 balances and TR is if those trade balances reverse. Then the accounting balances normalise and you get real value for your past exports.

Let me simplify it: the Germans are being given a ticket in exchange for their exports. The ticket entitles them to buy Greek and Italian exports. But only once the Greeks and Italians export more to Germany than the Germans export to them. Which won’t happen because the ticket system prevents this…

It’s a complete mess. A lose-lose situation.

But perhaps the real threat here is that Europe will run out of acronyms for its various monetary unions. Although, they just recycled the ERM name, creating the ERM2 when the first failed.

Centrally planned failure

What bothers me about the rouble zone, Latin Monetary Union and eurozone is the same thing that always bothers me.

Whenever you have central planning, it always fails. And by fails I mean it delivers a bad outcome until people abandon it for a new central plan.

This is true of everything from rent control to price controls. So why don’t people realise it is also true of currency controls?

The strongest vestige of central planning in our economy today is the central bank. It rules half of every transaction by controlling the opportunity cost of spending your money – the interest rate.

What parts of our economy does the central bank affect most? Inflation, housing, GDP growth and sovereign debt. A central bank’s toolkit is applied to those assets and indicators by design or intent.

The result? Isn’t it painfully obvious?

Precisely the parts of our modern global economy which are most affected by central planning are the parts that blew up, lagged and disappointed since 2006.

But critics of capitalism blame free markets!?

It’s like those Soviets who blamed the black market for the collapse of socialism. The black market is the only part that worked! Except for the security state…

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: The End of Europe