The EU’s pride is the latest casualty of Donald Trump’s trade war. But it’s not the only recent victim.

The push for “fair trade” is causing all sorts of problems in every corner of the world. The worst seem unrelated at first. Today we dig into how the dominos are lined up. And where they lead.

Yesterday, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) delivered a rather immense victory to President Trump and Boeing at the expense of the EU and Airbus. The trade policy arbiter ruled that the EU’s and EU member states’ support for their aircraft company are illegal.

The case goes back to 2004, so the losses and claims of Boeing amount to vast sums – about $22 billion according to Boeing.

The WTO solution to the problem of unfair trade practices is of course more unfair trade practices. The US can now request an estimate on permitted retaliatory trade measures. Which Boeing estimates will be “the largest-ever WTO authorization of retaliatory tariffs”.

I don’t know which utter nincompoop came up with the idea of permitting retaliation in a trade war instead of resolving the underlying problem and ruling for compensation.

Imagine if the principle of retaliation as compensation was valid in other courts. Family courts… war crimes tribunals… traffic incidents… “We rule the wrongdoer is allowed to continue his misbehaviour, as long as his victims can do it back.”

Most embarrassing of all, the WTO court ruled that the EU had failed to comply with its 2011 ruling. That’s a dramatic vindication of what Trump has been saying, and what the world criticised him for. Once again, he has the legal high ground.

Trump’s trade representative was quick to press the advantage: “This report confirms once and for all that the EU has long ignored WTO rules, and even worse, EU aircraft subsidies have cost American aerospace companies tens of billions of dollars in lost revenue,” said Robert Lighthizer.

Trump now has proof to point to on his claims of “unfair trade”. He’ll ramp up his efforts.

But he hasn’t quite cottoned on to the consequences of his success just yet…

Emerging market meltdown

A few weeks ago we looked into the emerging market (EM) meltdown around the world and how US trade policy was an underlying cause. The US central bank’s plan to tighten monetary policy is pushing up the dollar and raising interest rates. Last night US Treasury yields hit the highest level in seven years.

A US trade deficit adds to the number of US dollars floating around the world. A shrinking trade deficit would reduce this supply, further strengthening the dollar. That’s what’s happening now, under Trump’s trade war.

The problem with a higher US dollar and higher interest rates in the US is that many EM companies and governments borrowed in US dollars. And they’re dropping like flies.

None of the 24 EM currencies tracked by Bloomberg rose in trading yesterday according to Zero Hedge. The Turkish lira fell to a new record low as President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced he’ll take responsibility for monetary policy if he wins re-election next month. The Argentine peso fell to a record low as the country turned to the International Monetary Fund. Brazil and South Africa’s debt and currency positions are deteriorating fast.

A week ago, Bloomberg declared the problem was out of hand: “Rattled Emerging Markets Say: It’s Over to You, Central Bankers”.

Fed chair Jerome Powell explained in reply that he doesn’t care: “There is good reason to think that the normalization of monetary policy in advanced economies should continue to prove manageable for EMEs [EM economies]” and “markets should not be surprised by our actions if the economy evolves in line with expectations.”

If the EM market debt debacle spreads into other debt markets, one is ripe for the plucking.

The AIG of countries

How does all this lead to your door? The answer is surprisingly simple. In a financial crisis, the UK fares very badly. Analysis by economist Michael Roberts on his blog in 2014 has the details:

Which major economy has performed the worst since 2007?

Who gets the prize? It’s Italy, the ninth largest economy in the world. Italy’s real GDP in Q3 2013 was some 9% below where it was at the end of 2007. And the next worst is the UK, now 1.3% down (Q4 2013). But which country’s workers have suffered the most in lost incomes and jobs since 2007? The prize goes to the UK, the 6th largest, with a combined loss of over 7%.

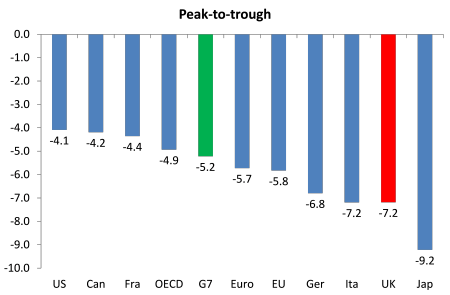

What the comparative data show is that real GDP in the UK underwent the joint-second largest contraction of the G7 economies during the 2008-09 economic downturn. Following the global financial shock, GDP in the UK fell by 7.2% between Q1 2008 and Q2 2009; this was the joint-second largest peak-to-trough fall among G7 economies. This is bigger than the fall in GDP in the G7 economies on average and bigger than in the European Union.

I think this confirms my forecast back in 2005 that if world capitalism went into a slump that the UK would suffer more than most because it was, more than any other, a rentier economy, i.e. its prosperity depended on its importance as a global financial centre where it could extract rent, interest and dividends out of the surplus value created by other economies. In the global financial crash, such economies were likely to take a bigger hit that those with a more productive base.

The drop in real GDP was even greater in Japan, which is not a rentier economy like the UK. But this was because Japan, of all the G7 top capitalist economies, is dependent on world trade, which took an almighty plunge in 2009. That other major trading economy, Germany, also dropped sharply, but by not as much as the UK. And the US, with a relatively small trade component in its GDP and not quite so dependent on its financial services sector, fell less, even though the world financial crash began there.

In the recovery period, the UK’s growth in the period following the recession has been slower than in other major economies. Average growth in the UK has also been slightly lower than that of the OECD total. Only Italy has been worse. Indeed, Italy has just stagnated at the level it reached in the trough of the GR. It is clearly the weakest of the top ten capitalist economies in the world.

Another way to think about this is that the UK is like the American International Group (AIG) of 2008 and 2009. AIG was a major intermediary and market maker in a long list of financial instruments back then.

The problem with this position is that you indirectly take on the positions of your counterparties if they can’t pay up. Even if you balance your books so that all trades of your clients are matched by another client betting the opposite way, if some clients go broke, then you’re left holding the bag on their opposing trade. You still have to pay out what the losing client can’t pay in.

The point is that Britain’s fortunes are closely tied to the health of financial markets. Which means the coming financial crisis will strike here particularly badly.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Related Articles:

- Pension mountain is growing faster than you can climb

- The pension panic is coming

- Why the European sovereign debt crisis is back

Category: Economics