Do you remember when a 1% drop in the stockmarket was nothing to get excited about? When 2.7% was a cheap interest rate for governments to borrow at? When a forecasted central bank interest rate below 2% would cause inflation?

Well, those days are long gone.

After an extraordinarily calm set of financial markets these last few years, two days’ worth of previously ordinary jitters have got markets in a panic. At least the newspapers are in a panic. They’re reporting on the falling markets as though it’s a crash already.

US Treasury borrowing rates hit 2.73%, the highest since 2014. The FTSE All-World Index fell 0.6%, its biggest drop since August. US stocks fell the most since Brexit and the biggest two-day loss since May (the month, not the PM’s election). The Volatility Index hit highs not seen since August too. European corporate bonds fell to six-month lows.

It’s probably the volatility index that’s most revealing though. This chart goes back to September of 2015.

The steady downtrend in the volatility of US and EU stockmarkets has been extraordinary. The uptick from the last two days’ “routs” are nothing… yet.

Even the usually positive news has a negative spin on it today: global stocks are off to their best start since 1987, the year they also crashed spectacularly in a single day…

Has the long run of manipulated market stability come to an end? Or is this just a perfectly normal correction?

And what is a normal correction in a manipulated market anyway?

Because market behaviour has been a matter of central bank and government interference for so long, even a small correction is terrifying. Especially when it happens in so many asset classes at once. It suggests central bankers and governments are losing control.

Central bankers make their presence felt in the bond markets for the most part. So that’s where you need to look for signs of trouble. Indeed, it’s the bond market action that features at the top of news stories about two days of falling markets elsewhere. Supposedly, higher interest rates are putting the fear into investors everywhere.

The irony here is a little subtle. Interest rates are rising because of global optimism. The global economy is growing well. Even Brexit Britain is doing well. The resulting low unemployment supposedly pushes up prices – something I’ve never understood given employed people are employed to produce more and that means supply expands, which keeps prices down. But still, inflation is a concern. And that adds central bank tightening to the mix of higher interest rates.

But here’s the problem. Can we really afford these higher rates?

The devil’s footprints

What if the economic growth is fake? What if it’s like the housing bubbles of the 2000s, or the tech bubble of 2000? What if interest rates rising will expose everyone is swimming naked and hasn’t been doing leg days at the gym? What if “the economic upswing shows the devil’s footprints”?

That’s the headline of an article written by Thorsten Polleit for the Mises Institute. Polleit is the chief economist at Degussa, a gold and silver processing company which is part of the biggest specialty chemicals company in the world.

A few years ago, I went to an event about investing. It was hosted at a posh hotel in the Austrian mountains near my mum’s house. Polleit was the guest speaker. You can’t imagine my surprise to discover someone giving a speech that matched my opinions precisely in German. People at our table couldn’t believe my ability to predict what he’d say next.

Polleit’s recent article explains how our economic growth doesn’t have honest beginnings. “Central banks have set it in motion with their extremely low, and in some countries even negative, interest rate policy and rampant monetary expansion.” A huge chunk of our economic growth is built on a foundation of cheap debt. If debt doesn’t stay cheap, it’ll be exposed and fail.

This time the central bankers’ implicit bailout is far more explicit than before: “[…] central banks have effectively spread a “safety net” under financial markets: Investors feel assured that monetary authorities will, in case things turning sour, step in and fend off any crisis.”

The ugly ending will be the same as last time. And the many times before that. High interest rates mean borrowers must actually be making money to pay up. Too many are not.

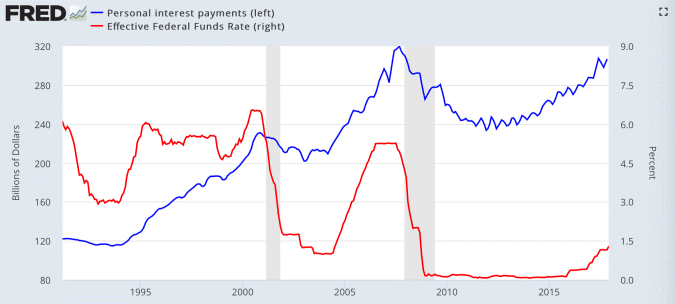

This chart from the Federal Reserve shows how interest payments are reaching the highs of 2007 in the US, despite interest rates less than a third as high. Imagine what higher rates will do.

John Authers at the Financial Times pointed out that the absolute levels of interest rates may not be the right comparison. Not just because the amount of debt is much higher now.

Interest rates have been in a steady downward trend for decades. If you stick a line on to a chart of this downward trend, you’ll notice something: “The two previous high points which form the […] trend line […] are the Friday before Black Monday in 1987, and early June 2007, just before the bottom fell out of the credit market.” And then stockmarket.

Well, we’re very close to hitting the downward trend line with another high point.

If yields go up, we’re in trouble because of unaffordable debt. And if yields go down, we’re in trouble because it signals a return to a crisis.

Who controls interest rates?

The confusing part is that central bankers control interest rates. So you’d think the false economic growth can go on for a mighty long time. They just lower rates each time there’s trouble.

But central bankers make mistakes. Like in the 1930s and 2007. And interest rates can only go so low.

Alternatively, central bankers might lose control of interest rates completely. Bond vigilantes and the funds owning vast amounts of bonds might not be interested in buying more. Pension funds will begin selling out soon to fund their liabilities.

If the downward trend of interest rates is about to reverse, then the 35-year reason to own bonds disappears with it. The moves will be big and interest rates will surge out of control.

A currency reset

The economist who explained all this was Ludwig von Mises. His theory is called the Austrian business cycle theory. And one of its tenets is that a false expansion driven by central bankers will eventually end badly:

There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.

My bet is on the latter. We’ll have the same sort of currency system reset as during Bretton Woods, the Smithsonian Agreement and many more. Central bankers have used up their powder. Interest rates can’t go much lower. Quantitative easing risks people losing faith in the currency.

Politicians will be forced to act. They’ll hit the “reset” button on the financial system.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble,

Capital & Conflict

Related Articles:

- Cryptocurrencies verging on useful

- Nobody will believe anything official

- A beginner’s Guide to Investing in Cryptos

Category: Economics