Buy low sell high, goes the old mantra.

So why is all the focus on buying?

There are always two parts to a trade or an investment, but most people spend the majority of their time focusing on the former.

When it comes to selling, we allow our emotions to come far more into play.

So how do the greats of investing say we should think about selling?

There are two main reasons to sell – bad news, or bad value.

I tend to focus on the latter.

I will turn first to Howard Marks, as so often.

Alongside Warren Buffett, his very existence as a fifty-year investor with huge success is a reminder that success in investing is measured in decades, not weeks or months.

The key to long term success is not short-term gains, it’s the avoidance of major losses.

Fear of missing out on gains is what makes people buy in at the very worst moments, the moments of peak euphoria, and peak prices.

With that in mind, it has to be important to be able to leave gains on the table, in order to reduce the risk of high losses.

Marks said in an interview in March, “The time to sell is not now, when everybody has a long list of problems and stocks are down 10, 11, 12%. The time to sell is when everybody says, I can’t imagine anything that could go wrong.”

According to Marks, “The greatest source of risk is the belief that there is no risk. When it’s obvious that the outlook is perfect, that’s a source of great risk.”

That is when we should be thinking about selling more.

It rings very true, but it’s hard to decipher right now. Because there is simultaneously a widespread acknowledgement of the many risks out there – it’s just that certain markets in America are ignoring them.

And again, I must point out that it depends whether you’re looking at the FTSE or the Nasdaq.

People want to draw comparisons between now and 2000, but never before have we had such euphoria at the same time as such powerful economic contraction.

I believe that if it’s right to be considered brave for buying low, then selling at high, extended levels can also be considered brave. The opposite should be considered greedy, or foolhardy.

But how then do we measure what counts as high or low? This is how we decide whether we should sell based on valuation.

Well, there are obviously a variety of metrics, but Warren Buffett’s favoured metric is market cap to GDP.

It’s currently at extreme record levels, which is unsurprising given that GDP has taken an enormous hit in the US, while markets there have soared to all-time highs.

Warren Buffett though, is pretty set against selling whenever possible.

He doesn’t quite live by his own advice to limit yourself to 20 asset purchases in your life, but he does hold things for an incredibly long time – decades and decades – in order to take full benefit of the compounding effect.

Buffett says, “The less prudence with which others conduct their affairs, the greater prudence with which we should conduct out own affairs”.

This echoes the line of thinking Marks always follows, which is to become more cautious as others become more reckless.

It’s countercyclicality in action.

Buffett has also said, “The stock market is a device to transfer money from the impatient to the patient.”

It’s important to remember that we are in this for the long run.

But selling does take place at a certain moment in time, and so some help in judging the short-term movements of stocks would be appreciated.

In the regard, you could look at the RSI – the Relative Strength Index.

It’s calculated by an algorithm that just says how strong buying has been compared to the average. It’s a ‘momentum oscillator’, which means it measures the velocity and magnitude of price movements.

A score over 0.7 means a stock or market is overbought and you can expect a correction soon, while a score below 0.3 means oversold, and that a burst upward might be around the corner.

As with anything, it’s not a hard and fast indicator, but it can help.

For example, here is Tesla’s RSI and share price for this year. You can see at the bottom, that buying when the RSI was well below 0.3 in mid-March would have preceded a comeback, and that it had been ‘overbought’ for a few weeks before its 25% crash this week.

The key thing to remember here is what Marks always says – just because something is overvalued (or in this case, overbought), it doesn’t mean it’ll go down tomorrow.

And markets can always remain irrational longer than an investor can remain solvent, as the saying goes.

And you can see that buying at high RSI levels can still be okay. For example, in July, you would still have seen good and almost immediate gains.

But the point is that if you can have the strength to leave gains on the table, the RSI can sometimes help with timing.

Moving onto Russell Napier, in his book Anatomy of the Bear (reviewed here), he looks at valuation above all.

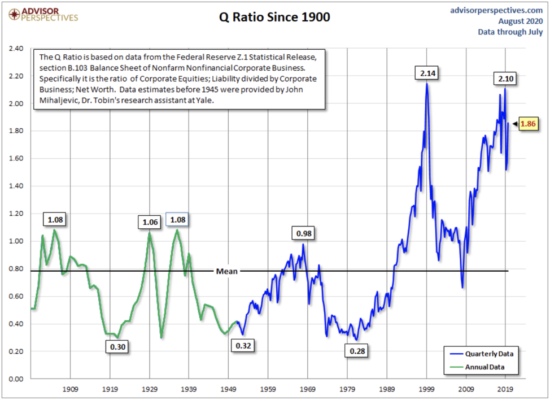

To help with that, he looks primarily at cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratios (CAPE) and the Q-Ratio.

The CAPE measures how expensive a market is relative to the profits of the companies its produced, while the Q Ratio measures how expensive a company is relative to the replacement value of its assets.

It’s measured by taking the market value of a company and dividing it by the book/replacement value of a company.

A score of 1 means they are equal. Napier sees a Q ratio of around 0.3 at all the bottom of all four great bear markets in his study. Currently it’s much, much higher, at just under 2.

Source: Advisor Perspectives

Source: Advisor Perspectives

It goes without saying that we are currently at extreme highs.

But does that mean we should sell? We should certainly be paying attention to these broad market measures, and recognising that we should proceed with caution.

With indexes reflecting record Market Cap to GDP numbers and extreme highs in the Q Ratio… As ever with me this year, cautiousness remains key.

Remember, there are two main reasons to sell: bad news, and high prices.

Since 2008, bad news has offered plenty of reasons to sell. But all of them have been swiftly replaced by good or better news.

This, however, is the first time where bad news has been met by extreme valuations and a notable absence of investor cautiousness. It’s the combination that makes me especially nervous.

News has never been worse, but in America, asset prices have never been higher.

Here in the UK house prices just surged to new all-time highs on record monthly figures.

The only thing going for markets is central bank complicity. And maybe it’ll prove to be enough, but no market has ever been sustained at these levels before, at least not for long.

If that narrative, of the Fed will save us, breaks down then we should all be truly scared.

FOMO

When we sell, we suffer from opportunity cost.

In markets, there are two main risks. Losing money, or not making money. Selling brings the latter into the equation, while holding leaves you with the former.

The decision to sell should depend on how you feel about those two primary risks.

Everyone talks about those people who bought Amazon, Apple or Tesla for a few cents back in the early days, or bitcoin for $10 in 2012.

But the reality is, very few people have the conviction to hold these things through thick and thin.

If you had indeed bought bitcoin for $10, it would have taken a high level of confidence not to sell when it first hit $100, and an extreme belief in its future not to sell at $1,000 or $10,000 – the latter representing a gain of 100,000%.

Far more common is to find people who bought bitcoin for ten bucks and sold most of it down over time.

As with gold, bitcoin is an asset with no yield, and so the only way to make money is by taking profits.

Of course, this is true of Tesla as well, which doesn’t and has said it doesn’t intend to ever pay a dividend (not including the enormous paychecks Elon Musk takes out of the company each year).

Every time you sell, you are suffering from opportunity cost – the risk that it goes up in the future.

One company from a portfolio I’m involved with was sold last year, but when Covid struck it turns out of one its air-quality control products has potential applications in detecting the virus indoors, sending its share price soaring:

Source: Google Finance

Source: Google Finance

So it’s tough.

There’s a lot to think about, and you can get punished or just unlucky. You can sell brilliant companies and watch them go up and up and up, and that’s tough. But if you know that you’re a person who’s more concerned by the risk of losing money than not making it, this feeling of missing out can be tolerated.

But if you held a stock that you felt was overvalued and then it crashed… that would be more frustrating.

Finding out how you would feel in different scenarios surrounding these two key risks will help hugely in building selling discipline, and making individual decisions to sell.

You don’t have to see it my way, but looking at legends like Buffett and Marks makes me very comfortable watching the Nasdaq going up, thinking that I know the FAANG stocks will never be able to ruin my life, because I don’t own a cent of them. I find that thought relaxing.

And anyway, I’ve got the energy transition, which is better. It’s niche, so I have an advantage, and it’s also in its earliest stages, rather than well-established. Ideal.

Anyway, my incredibly non-committal conclusion is that we should all spend more time thinking about selling, especially right now with bad news all around and valuations at record levels.

Just remember, it’s better to sell when you can, not when you have to.

To finish, I’d like to suggest a few questions that you can ask yourself, the answers to which will help you find out if you should do a bit of selling.

- Which do you fear more, losing money or missing out on making money?

- Would you buy the stock at current levels, if you didn’t already own it?

- If a stock you held fell by 30%, or 50%, would you buy more?

- Looking at your whole portfolio, are you happy enough with the securities you own that you would hold them through thick and thin?

- Are you confident that you wouldn’t sell if panic struck the market?

- And are you the kind of person who will have to fortitude to buy back in once things have fallen significantly?

Finally, a few quotes from the great investors, about keeping calm.

“The investor’s chief problem—and his worst enemy—is likely to be himself. In the end, how your investments behave is much less important than how you behave.”

And, “The intelligent investor is a realist who sells to optimists and buys from pessimists.” – Benjamin Graham.

“Far more money has been lost by investors trying to anticipate corrections, than lost in the corrections themselves.” – Peter Lynch.

All the best,

Kit Winder,

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Economics