A question to begin today’s letter: how do you turn an unpopular academic concept into an everyday legal reality for millions of people?

Think of this question in the spirt Jack Ryan tackled a similar problem in The Hunt for Red October. How do you get someone to want to get off a nuclear submarine?

You’ll know the answer when it comes to you. The mental trick is not trying to solve the problem directly. It’s creating the conditions in which people do exactly what you want them to of their own free will, with urgency. I’ll come back to that in a moment.

But first, as expected—given the positive retail sales figures reported earlier today by the Office for National Statistics—the Bank of England (BOE) has done nothing, more or less. The Bank’s monetary policy committee voted to leave the Bank Rate at 0.25%–still a 322-year low.

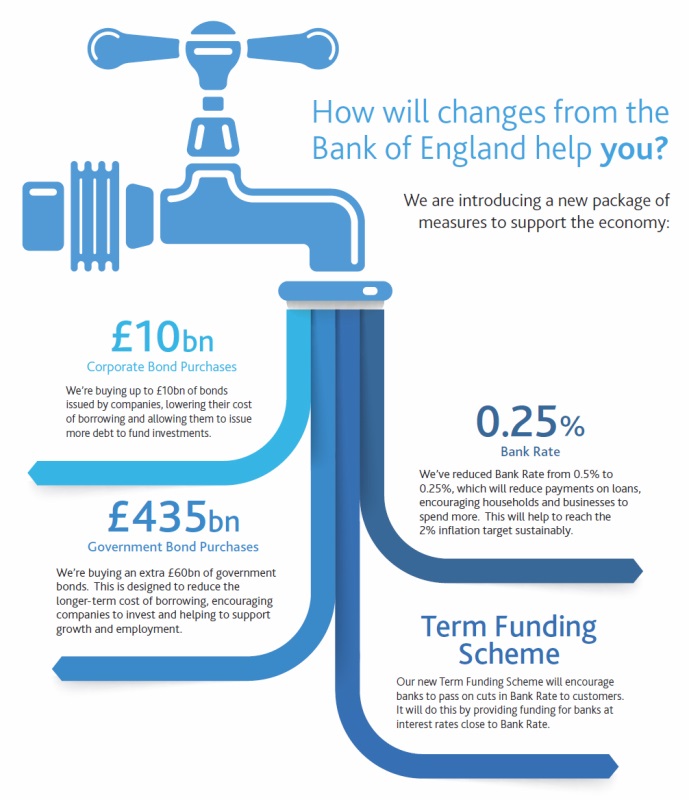

It also voted 9-0 to continue the Bank’s bond buying program, which consists of purchasing £60 billion in government bonds and £10 billion in corporate bonds. What does that mean? Have a look at the image below from the Bank’s website.

Source: Bank of England

Before its August 4th decision to purchase £70 billion more in bonds with money that never existed before, the Bank already had a sizeable portfolio of assets, also purchased with money that had never existed before. That’s £435 billion on the balance sheet, or about 24% of UK GDP.

The Bank’s QE program, in terms of GDP, is second only to the Bank of Japan’s. And today, I learned from Tim Price (via the latest edition of The Price Report) is that the BoE’s leverage ratio is also the second-largest in the world. The leverage ratio is the total assets divided by core capital. Both the BoE and the BoJ have leverage ratios of 120%.

Why does that matter? For a private sector firm, the higher your leverage, the easier it is for you to be rendered insolvent by a small fall in the value of your assets. That little fact has led many people to speculate how central banks could become insolvent in a sovereign bond crisis, given that government bonds make up the bulk of new central bank assets.

In theory, a central bank can never become insolvent. When you have a printing press, you just print more money to buy new assets to bolster the balance sheet. Sure, money isn’t capital. But when your cost of money is nothing, you can always buy high quality capital, right?

Maybe not right. But let’s leave that aside for the day. My main point is that Carney and company are already further out on a limb than many people would like to believe (or are aware of). Cancelling the increase in QE would have been the most bullish move the Bank could have made. Instead, like I speculated he would yesterday, the Bank ‘checked’ in the giant global game of currency poker.

The orchestrated emergency

All eyes now turn to the US Fed and the Bank of Japan. The Fed is likely to do nothing at all. It’s hinted at rate rises. But the data don’t support it. And Japan?

That’s where all the crazy happens. But let’s not talk about bond yields any more than they have to. The stirrings of revolt in the bond market—the resurrection of the bond vigilantes—have died down. It gave me time to go back and read a paper presented at the recent central banker pow wow in Wyoming.

I meant to read the paper last month. You can find it yourself here. It’s called, innocuously, ‘The case for unencumbering monetary policy at the zero bound.’ It’s by Marvin Goodfriend from Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh.

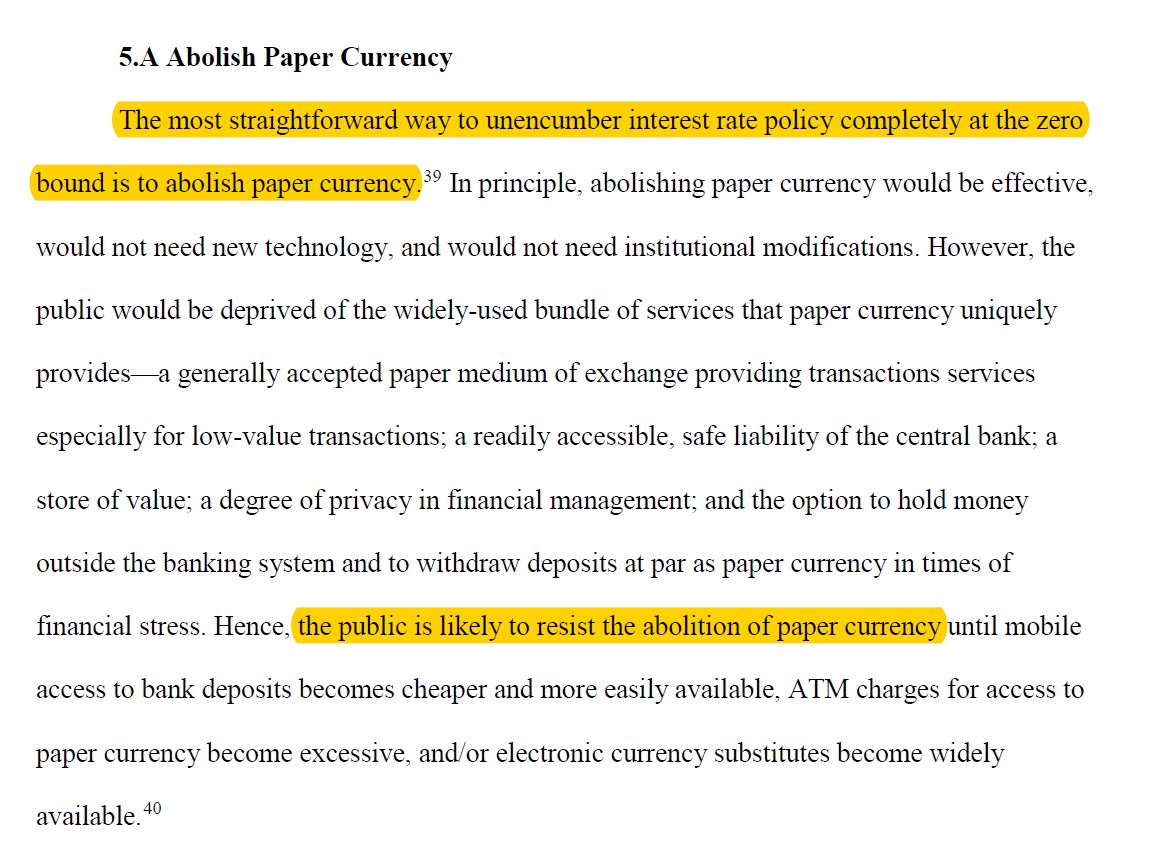

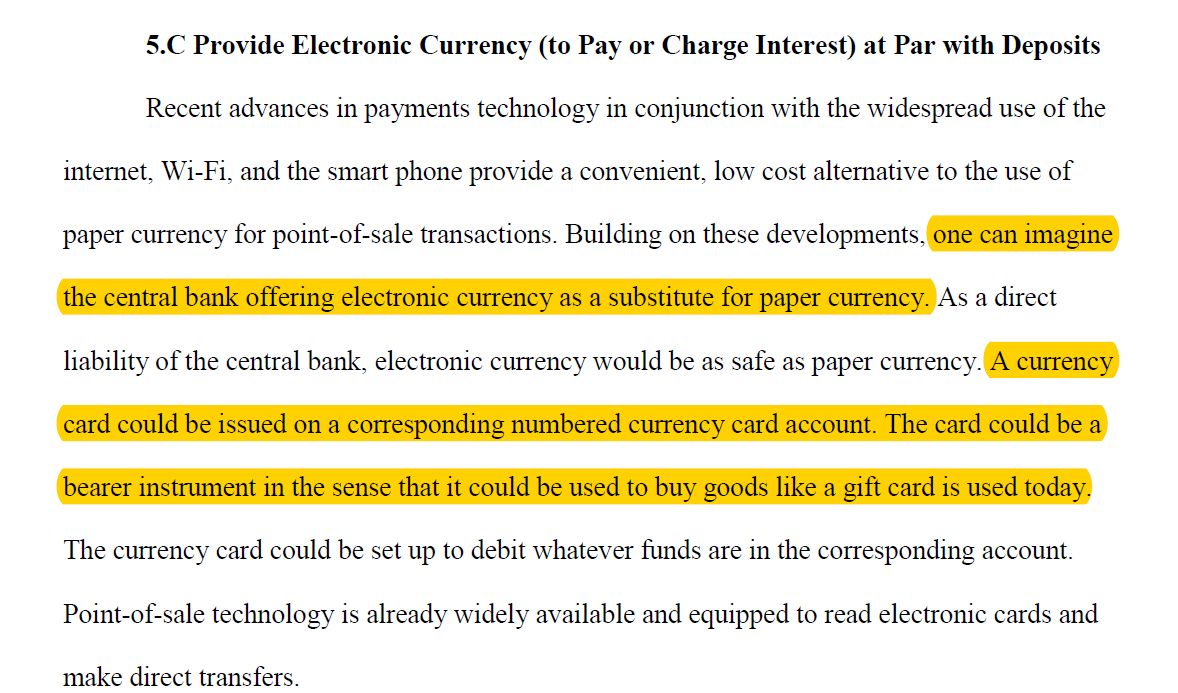

Don’t be deceived about the title. The paper is how about to implement a cash ban when you know people opposed to it. The key parts are sections 5a and 5c. And because you wouldn’t believe me if quoted from the paper, I’ve taken a screen shot from the paper and highlighted the relevant bits. Read it and weep.

You COULD make this up. But it’s getting harder and harder to stay one step ahead of the financial authoritarians. Right now, all of this is a text book academic discussion. It’s a template, a blue-print, a plan. But every good plan to take away freedom and liberty and exert more control requires a catalyst, a crisis that makes people the chains you’re going to shackle on them.

Back to the question at the top, then. How do you turn an unpopular idea into the law of the land?

You need to orchestrate a crisis. In this case, you need to give people a compelling and urgent reason for wanting to get rid of their cash and using an electronic currency card. How do you do it?

Come on!

Think about it. It’s not that hard. I’ll reveal the answer to you tomorrow.

Category: Economics