Black hole sun

Won’t you come

And wash away the rain?

Black hole sun

Won’t you come?

Won’t you come?

– Black Hole Sun, Soundgarden (1994)

Watching one of the longest bull markets in history march upwards, mounting political obstacles and leaping off them to ever greater heights, one has to ask: when does it all end? When will we see a great reckoning, a black hole sun wash it all away?

A couple of weeks ago, I asked a fund manager from a well-respected investment house how business was doing. His response?

If the market doesn’t crash soon, they’re in big trouble. In fact, in his words, they need a recession right now.

What his firm does is try to generate returns that are uncorrelated with the rest of the market, so bear markets do not destroy its client’s capital.

It’s a cautious approach to the chaos of financial markets, and one that has garnered the firm much respect over the years.

But these days, caution isn’t popular – central banks have seen to that. As loose monetary policy has jacked up the stockmarket, people are pulling their money out of expensive wealth protection strategies.

One of the primary goals of quantitative easing is to push investors into riskier assets – in a way, his firm has become a casualty of the Bank of England.

As hedge fund manager Chris Cole of Artemis Capital said last year, “It can be hard to hang out with the designated driver when everyone is getting drunk from the monetary punchbowl.”

Drunk is the word. But for how long will markets continue their relentless stagger higher?

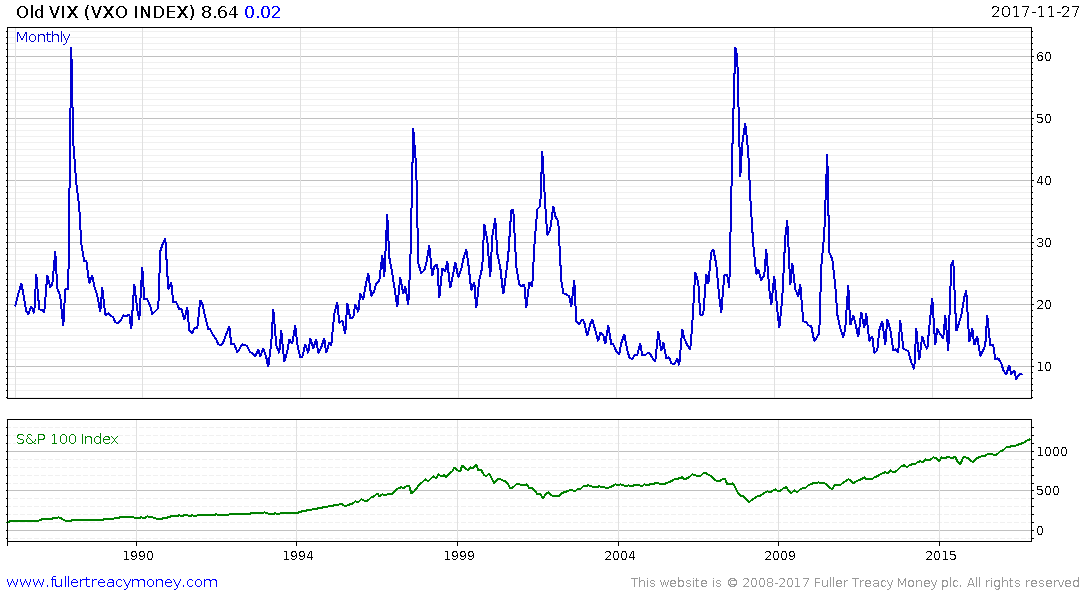

The VXO index, which is the market’s expectation of short-term volatility in the S&P 100, continues to wallow in the depths, moving opposite to the index itself:

While the S&P 100 has more than doubled since 2009, volatility has been cut in half… and then some.

“Markets take the stairs up and the elevator down”, the saying goes, which is why volatility can be seen spiking when the S&P declines.

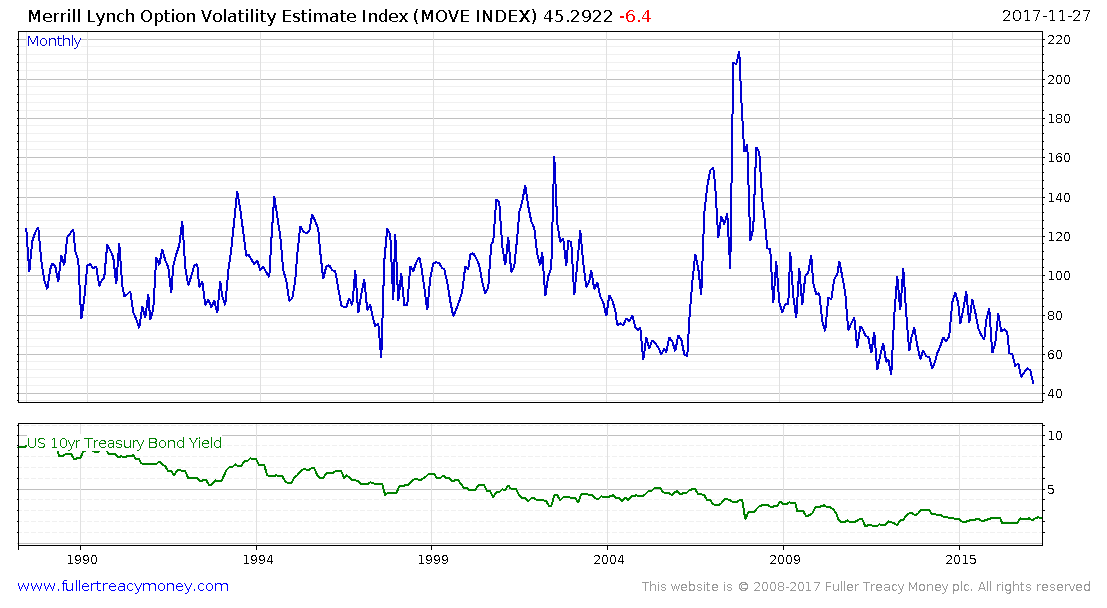

A similar story can be seen in the bond market. The Merrill lynch Option Volatility Estimate (MOVE) index is similar to the VXO, measuring expected volatility in US government debt. It too is at all-time lows – while US Treasuries have been in a bull market; as their price increases, the interest they pay to investors is crushed (in green).

From a volatility perspective, it’s never been this dull. It’s no wonder that a managing director of Deutsche Bank recently remarked that 2017 could be “the most boring year ever”.

But for those invested in US equities and bonds, the year hasn’t been boring at all. In fact, this year has been a gift that just doesn’t stop giving, a grand party.

And one which they don’t think will end, either.

In a survey of its clients, Citibank discovered that 85% of them did not expect a US recession in 2017 or 2018.

Stocks at all-time highs. Expected volatility at all-time lows.

Is it time to bid farewell, and leave the party – sell stocks, and find refuge in cash and gold?

Akhil Patel doesn’t think so – in fact, he thinks this party is just beginning. Click here to see just how wild he expects it to become.

I’m not nearly so optimistic. Sooner or later I expect the market will vomit all the cheap credit it’s sucked down its gullet in a horrific unwinding of excess.

But the issue, of course, is timing.

Grab your coat

When is the best time to leave a party?

Leave early and you may miss all the fun. Leave it too late, and you run the risk of things going awry – often at your expense.

Alcohol, the liquid social leverage, carries many of the same risks financial leverage does. Just as it can amplify fun, it can make a bad experience even worse.

And just as markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent, parties can continue longer than you can stay standing.

Those who’ve sold out of the market at the prospects of Brexit and Trump and are waiting on a correction are currently missing all of the fun.

Those with the ability to sense when the mood at the party has shifted, and exit at just the right time are a rare breed.

Those who can call the top of a market are even rarer.

All-time highs and lows are not necessarily predictive of the future, unless what is being measured reverts to the mean over time. Expected future volatility and the S&P 500 do not mean revert, and so their use as an alarm clock may be limited.

The cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio, or CAPE ratio, is a mean reverting indicator that has stood the test of time for valuing stockmarkets. The S&P 500 (a broader metric than the S&P 100 mentioned previously) now has a CAPE of 31.56.

This is a higher level than the US stockmarket was right before the Great Depression… but much less than its all-time high of 44.19 during the dotcom boom. Should this bull run deliver even greater returns than before, you’d be leaving an awful lot of money on the table if you sell now.

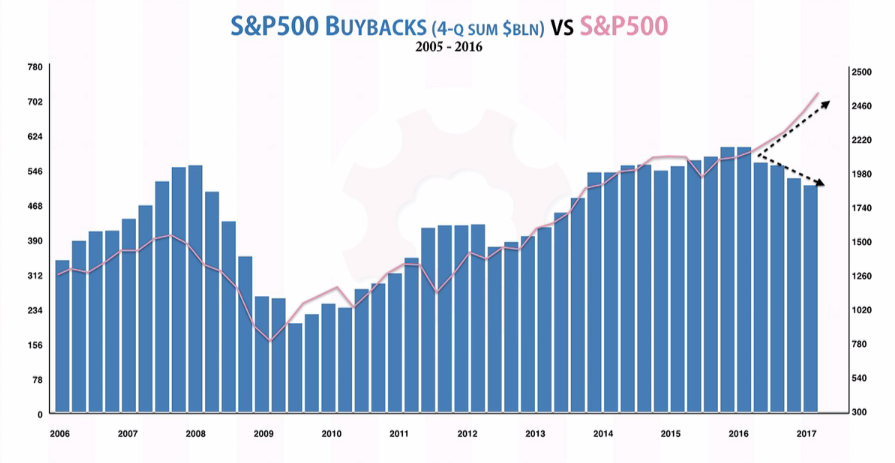

The chart below, courtesy of a presentation given by Grant Williams, is enlightening. With interest rates at such all-time lows, companies can now borrow cheaply to purchase their own shares back from the market. This boosts the price of those shares by reducing liquidity and boosting share metrics such as earnings per share, or EPS. (Bear in mind that many company executives are paid bonuses based on the EPS of their companies, making such a system highly prone to abuse.)

Source: Presentation by Grant Williams at the 2017 Stansberry Research conference

As you can see, the recent bull run in the market has been heavily supported by share buybacks… until recently. If the data is correct, the market is running on fumes. Nausea may come next.

One gentleman I know, through years of experience treating alcohol as an endurance event, has developed the ability to maintain a conversation while being sick, keeping his tone of voice clear and even between convulsions – as if he were just enjoying another pint.

Passive investors during the next bear market will need to develop a similar skill.

Such activity, while impressive in a grotesque way, is not recommended.

But that’s alright. Because you don’t have to invest like the other drunken revellers at this party. There are alternatives out there. You don’t have to gorge on the central bank punch bowl and deal with the splitting headache tomorrow.

Charlie Morris, in his latest issue of The Fleet Street Letter, explained what he learned from the 2008 crisis, and pointed out that many of those who made money (from the pain of other market participants) failed to produce similar returns in the years that followed. The heroes of the crisis, in his words, were those who made a tactical retreat – to fight another day. For more of his observations and access to his investment advice, click here.

Tim Price’s primary objective is protecting the capital of his clients and readers, and recommends you avoid the party punch altogether. In London Investment Alert he details not only how to protect and grow your capital through the coming crisis – but how to deal with the financial martial law that will follow it.

Until next time,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Southbank Investment Research

Category: Economics