Konnichi wa from Japan.

I’m here looking into Japan’s demographic disaster. And trying to solve it by meeting the potential in-laws.

Japan is 20 years ahead of the rest of the world when it comes to demographics. Which puts the rest of the world at the cusp of a dangerous demographic slope.

If you think demographics are important to financial markets and you want to make predictions about our own prospects, then taking a look at Japan is a must. Here’s the Japanese stockmarket for one:

Could you stomach a steady 70% decline over 20 years?

More on that in coming days. First, what’s going on in the financial world?

The US stockmarket seems to be clutching at straws. And yesterday one called Trump snapped.

The bad news finally caught up with the US president. His former FBI director leaked information, he’s going to be investigated by another former FBI director and the media circus over his release of information reached a furore. Stockmarkets took a hit.

It’s certainly good entertainment. If only your personal wealth wasn’t at hand. The FTSE 100 dropped too.

I doubt that Donald Trump is truly the key to the stockmarket. There just isn’t much else going on. That’s why the Volatility Index (Vix) is so low. At least it was until yesterday. Trump’s shenanigans is the only thing worth trading.

Remember, as the Russian economist Hyman Minsky said, stability breeds instability. If something cracks now, it’ll turn into a rift fast. So what do you do?

Dangerous diversification

Diversification is the one thing every financial advisor agrees on. Which should make you suspicious in the first place.

Apart from being legally mandated to promote diversification, financial advisors benefit from it. It increases the amount of things they need to be doing for you and can charge you for.

But does it work?

That depends on what you expect it to do. Higher returns? Nope. Less volatility? Sort of.

Theoretically, diversification is an ok idea. Sort of like sub-prime mortgages. You can shoot holes in it but the premise isn’t bad. If you ignore the bad aspects, the whole thing can get out of hand. That’s the point we’ve reached today in diversification.

It’s a bit like the efficient market hypothesis. It only holds true to some extent if people don’t believe it. If everyone fully diversified, there’d be no real thought to what makes an investment good or bad. Stock prices would be determined by buyers and sellers without regard to prices, just allocations. Think about how much pension and savings money is ploughed into markets without a thought except for diversification.

A lesson from crises

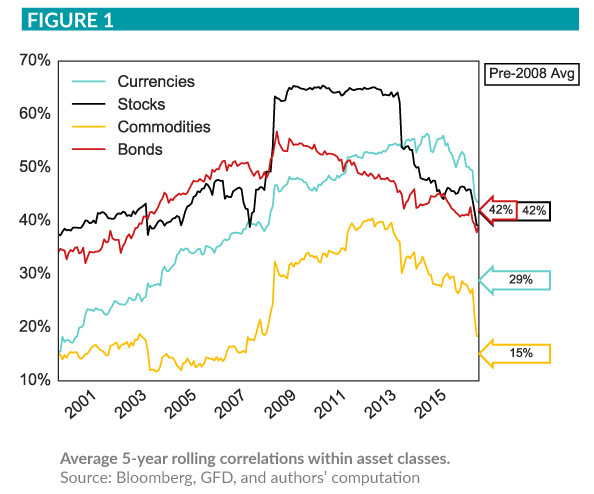

The real problem with the concept is that it breaks down when you need it. This chart from Two Sigma shows correlation – the tendency of different investments to move together. This is within an asset class, so the correlation between stocks is measured, not the correlation between stocks and bonds or any other combination.

The lesson is that correlation spikes during crises. Which is precisely when you don’t want it to spike. Your negatively correlated stocks are supposed to go up to offset the losses in the positively correlated stocks. Instead, they join the rout.

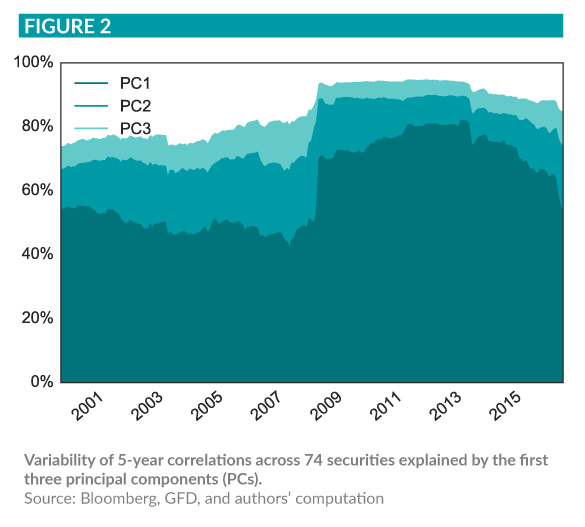

What about correlation between asset classes – stocks and bonds and commodities and currencies? The story is much the same. Only three factors determine more than 90% of the correlation during a crisis.

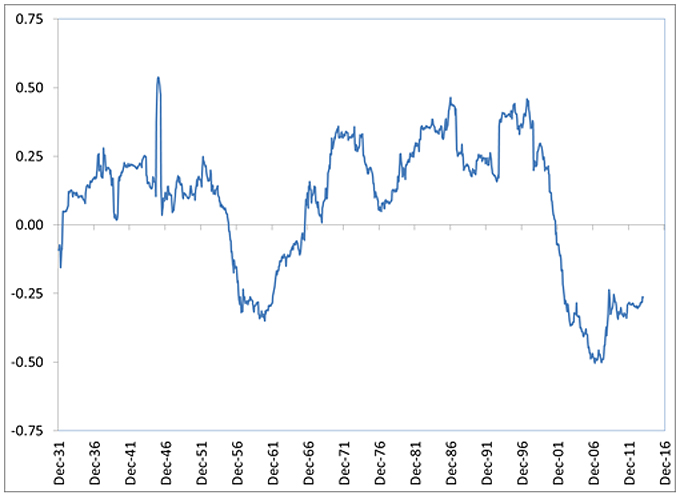

This chart from a Forbes columnist shows the rolling five-year correlation between US stocks and five-year Treasury note. There isn’t a textbook theory to explain how it can be positively and negatively correlated about evenly.

This chart from a Forbes columnist shows the rolling five-year correlation between US stocks and five-year Treasury note. There isn’t a textbook theory to explain how it can be positively and negatively correlated about evenly.

The answer to what’s going on is simple. And it’s the same answer to most other questions in financial markets at the moment – central banks.

Asset price movements are determined by central banks these days. Both their epic purchases of investments and the potential to do so.

In a crash, central banks buy everything. As the crash wanes, they try to sell. They’re such huge players in the market that their moves dominate. Japan leads the world here too, by the way.

The only major question you face as an investor in any asset class is whether central bankers can prevent a crash indefinitely…

Japan update

Japan is like the Germany I grew up in. Before the harsh reality of moving to Surrey and attending a posh British school for my first year of education. Tough times…

Six-year-olds take the train through Osaka alone without a care. Parents leave their kids at the park without a thought because one of the other parents will take care of them. The children share their toys, ride each other’s bikes home because they’ll bring them back tomorrow anyway, and most can do moves on the monkey bars that would make a workplace health and safety inspector pass out. The kids can play in the dirt all they like, but woe betide forgetting to swap your shoes for slippers as you enter the spotless house.

In other words, this is the perfect environment for raising kids. But there aren’t any. At least not according to the statistics, which clearly don’t apply to the local playground. Japan is set to lose 15% of its population in the next 30 years. And more than 40% will be over 60 by then.

My best guess as to what’s going on is all about the famous Japanese work-life balance. It doesn’t balance and the last thing people want to add to that is kids. It would tip them over the edge, no matter how well behaved they all seem to be.

Matanee,

Nicku-san

Category: Economics