What makes a nation go from being incredibly rich to incredibly poor?

The London Investment Alert’s Tim Price is out with a warning for Britain. He’s predicting we’re in for a new national crisis. One that you need to be prepared for. Take a look if you haven’t already.

But there’s one thing missing from Britain’s coming decline. The common denominator between all these, as described by a former planning minister of Venezuela, Ricardo Hausmann:

The most frequently used indicator to compare recessions is GDP. According to the International Monetary Fund, Venezuela’s GDP in 2017 is 35% below 2013 levels, or 40% in per capita terms. That is a significantly sharper contraction than during the 1929-1933 Great Depression in the United States, when US GDP is estimated to have fallen 28%. It is slightly bigger than the decline in Russia (1990-1994), Cuba (1989-1993), and Albania (1989-1993), but smaller than that experienced by other former Soviet States at the time of transition, such as Georgia, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Ukraine, or war-torn countries such as Liberia (1993), Libya (2011), Rwanda (1994), Iran (1981), and, most recently, South Sudan.

Then there’s the story of Argentina. Like Venezuela in 2001, it was the wealthiest country in South America once. About 100 years ago it was one of the richest countries in the world, topping out Germany, Italy and France. People used to say “rich as an Argentine” and Buenos Aires was next to New York as a destination for emigrating Europeans.

It’s not just wealthy countries that get trashed. China’s Cultural Revolution, Russia’s communism, Pol Pot’s Cambodia and East Germany’s comparative loss after World War 2 all feature. And Japan’s isolationist Sakoku period which left the country falling behind the West.

And so, what is the cause of these declines?

It’s hard to tease out symptoms from causes. Inflation features in most of those examples. Anyone on the opposite side of history to the US seems to get kicked in the teeth economically too.

Trade restrictions are top of the list of similarities. When countries reduce trade in some way, they decline. Vast natural resources pop up on most of that list too.

But what do all those examples share?

The common denominator

Perhaps the most important common denominator is government. In all of those examples, government policy went haywire in some way.

The variety in how government grew is great, but the initiator of trouble is the same. It’s faith in the government, or empowerment of the government, regardless of the various motives, ideology or intentions.

In the depression before the Great Depression, the US government did nothing and the economy quickly recovered. But during the Great Depression, government ran amok with all sorts of new policies. The results are still talked about today.

In war-torn states, the government’s involvement is obvious. As in communist and fascist countries and their various revolutions.

Trade has to be actively restricted by someone and taxation of natural resources tends to finance government gone wild longer than ordinary expropriation can.

The common denominator for the decline of countries is government. And the reverse is also true. More on that another day.

The propensity of power to destroy is a phenomenon we consider perfectly obvious in our day-to-day lives. Power imbalances inherently lead to disasters over time. That’s why the longer lasting institutions of the world have checks and balances to the powers held. The US constitution was written to restrict power while other nations saw theirs assign power.

I remember watching a reality TV show about living like a pirate. Everyone got along well until someone was elected captain. His awesome authority completely changed him and he was soon made to walk the plank by his shipmates.

Admittedly it was part of the game that a captain had to be elected each round, but it was fascinating to watch the contestants battle over who should be captain over and over again without realising it didn’t matter. The various disasters were different depending on the leader, but there was always a mess.

Britain’s decline

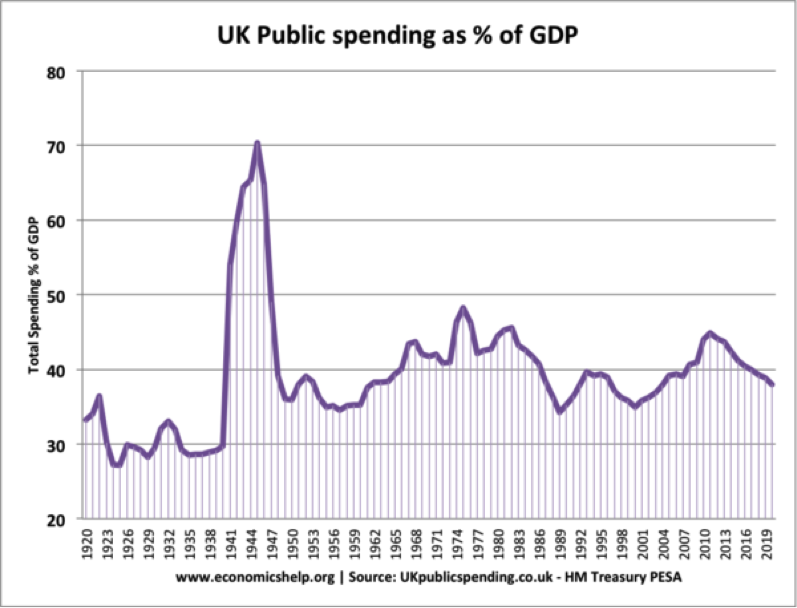

If you look at the British government’s involvement in the economy since World War 2, measured as government spending as a per cent of GDP, it has surged in anticipation of a crisis and then fallen during the recovery. Each time government spending rose above 40% we hit a major crisis.

The mess of the late 70s, when we had to ask the International Monetary Fund for a bailout, was preceded by a rise from 35% to 43%, and then a blow-off during the crisis. The 2008 financial crisis saw spending rise in a repeat of the 70s.

Perhaps government is not the cure, but the cause of economic trouble. Perhaps government doesn’t end recessions but prolongs them. Or perhaps government spending gives us instability, not stability.

The good news is, we’re in a downtrend in government spending as a per cent of GDP in Britain for now. At least according to projections.

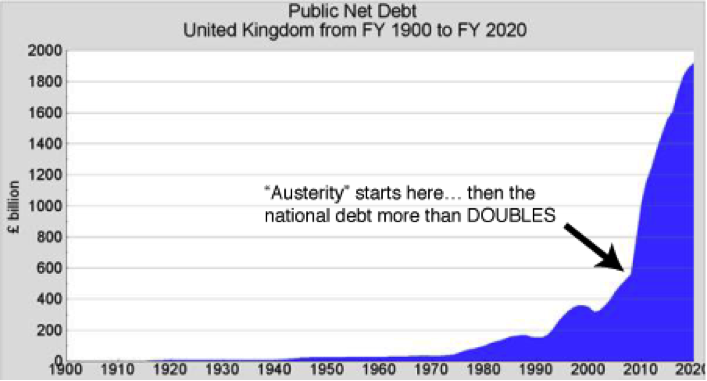

But that rather contrasts with this chart from Tim Price’s research:

Source: ukpublicspending.co.uk

Because, of course, it’s not just spending that matters. And therein lies the risk identified by Tim.

Bitcoin booms

Bitcoin is back at new all-time highs, the controversy over SegWit and the fork long gone. That’s perfect timing for thousands of readers who signed up to receive our own Sam Volkering’s guide to cryptocurrencies in the weeks when the bitcoin price was low.

But the cryptocurrency bonanza is only just getting started. New, innovative and improved cryptocurrencies are in the pipeline. They have all sorts of new and intriguing features. Not to mention the potential to repeat bitcoin’s stratospheric rise in value.

In other words, there’s still plenty of time to get in, with the help and guidance of Sam.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: Economics