Bond investors are turning to John Denver songs to make money.

Yes, you read that right. Country Roads and Leaving on a Jet Plane have become a substitute for bonds. Such is the state of the fixed income market. Who would have thought that the future would become so barren of promise, that credit investors would turn to music for interest payments?

I’ll tell you how this works in a second. Let’s start with why this has happened in the first place.

Thanks to central bank intervention, both short- and long-term interest rates have fallen in tandem in recent years. Central banks lowered long-term rates by buying sovereign bonds, making them more expensive. The interest they pay as a proportion of their price – their “yield” – dropped dramatically.

Investors who rely on interest payments (like pension funds) have had to use their imagination to keep making money. This is known as “reaching for yield”, or as I like to call it, “walking the plank” – for they are having to take more risk in order to keep their heads above water.

Walking the plank has involved (so far) buying ever more equities, junk debt, and the use of derivatives to enhance returns. And although the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have begun raising interest rates – which should provide some relief for the yield starved – demand for junk debt has not changed.

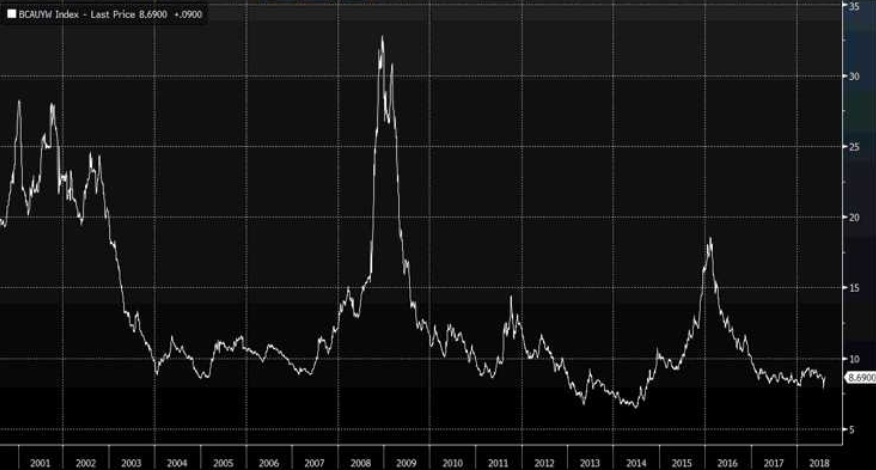

The chart below tracks shows the yield for the lowest rated (least creditworthy) junk bonds in the US. As you can see, yields are close to their 2014 lows.

The yield famine continues. And it’s driven yield investors to all kinds of strange places.

I recently attended a presentation on alternative yield strategies at Deutsche Bank’s HQ at London Wall (possibly chosen for the presence of “DB” in its postcode).

For those wanting high yields in a low-yield environment, the hedge fund analyst presenting detailed the “private credit solutions” Deutsche has been offering.

The markets bond investors are exploring to find yield ranged from the exotic to the bizarre – from sports finance to art lending.

Although bond investors cannot find high-yielding assets in the US or Europe, they can create them by offering bridge loans to fast food franchises, or leasing ageing commercial airliners (17-25 years old, the less landings the better).

Music copyrights are now a bond alternative. The rise of music streaming services like Spotify has made royalties profitable again now that audio piracy is less common. And the market is inefficient – musicians and their estates rarely understand how the rights to their music will be used to generate returns, and so don’t price it accurately. Bought in portfolios, the rights to music can yield high returns for several years.

Country Roads by John Denver is an example of this. Deutsche partnered with Kobalt, a music rights firm, to purchase a portfolio of John Denver tracks. Kobalt then used its contacts to make Country Roads the soundtrack to a Google advert in the Super Bowl.

After the advert was released, American football fans got the song stuck in their heads and started listening to it again. The royalties from streaming services rolled in and the music investors in the song made 400% on the rights.

It’s a sign of the times that something so everyday – music – has turned into a financial instrument. That the songs you may hear on the radio, or on TV, are now potential yield instruments for investors destroyed by low interest rates. Where next down the road of risk will investors travel in search of yield?

Wherever it goes, that road faces an earthquake.

The “risk curve”, running from bonds to stocks, to even riskier assets like derivatives and now the likes of music royalties, starts with one assumption: that sovereign debt, right at the beginning of the curve, is risk free. It isn’t.

When Italy breaks that spell, it’ll be interesting to see how the tower of assets built upon that assumption will fare. This country road may not be taking us home after all.

Until next time,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Southbank Investment Research

Category: Central Banks