I’ve lost my faith in money printing for today’s Capital & Conflict. It’s always a good idea to ask yourself, “What if I’m wrong?”. Especially when you’ve got Southbank Investment Research’s best and brightest giving you funny looks for temporarily believing in the supernatural powers of central banking.

Today we pick up a theme that four of our newsletter editors explored at the end of 2016 in a round table discussion caught on video.

Akhil Patel of Cycles, Trends and Forecasts described a particular way of looking at the last 17 years. We had the synchronised global economic expansion of the early 2000s. Then the synchronised global monetary expansion from 2008 until today. So what’s next? A synchronised global fiscal expansion is the obvious pick.

It stands to reason that quantitative easing (QE) will fail, or just end, just as the economic growth spurt of the early 2000s did. Something will have to fill the void. Unless you want to go cold turkey after trillions of dollars in monetary drug got pumped up financial veins.

The replacement for QE?

Synchronised global fiscal expansion – the end of austerity. There will be new bouts of infrastructure spending, guns and butter. With record low interest rates, record high butter prices, North Korea agitating and political populism on the rise, now is the time for governments to lever up. Think of it as a QE for the people (and their enemies).

Financial markets have had their share of the money. Now it’s time for the man in the street to get their share. And only a politician can do that. Vote for Jeremy!

There’s a particular reason fiscal policy is set for a comeback. Inside the eurozone, one monetary policy applies across all nations. Which means it’s the wrong interest rate for most of them. The result is what the new Czech president calls a two-speed Europe. And it’s why he wants out of the planned adoption of the euro.

But euro countries’ fiscal policy can vary. It can be adjusted to fit local needs. Especially if the EU suspends its budget rules under populist eurosceptic pressure, as Akhil suggested in the video. Without their own monetary policy, eurozone countries will demand more flexibility in fiscal policy, setting the stage for a boom in government spending.

What this environment means for the euro is awfully difficult to think through. We’ll leave it for another day.

But can governments afford to borrow more money?

Economists are concerned about government debt levels as it is.

The answer is that governments can borrow far more money, despite the fact that it’s a terrible idea.

Consider Japan. They’ve swayed back and forth between QE and fiscal stimulus for more than 25 years, maintaining impossible levels of debt. As long as central banks back governments, there’s no reason for a government bond crash. That’s why yields in European sovereign bonds are so low now.

The world I’m painting for you is unlikely to play out, in my opinion. Central bankers have plenty more assets left to monetise and austerity is still popular enough in the wake of Greece.

But a transition from monetary to fiscal policy does make a lot of sense if you take a look at what’s going on in the world, especially politically. If financial markets can be pumped, so can government spending.

How it could all go wrong

Unfortunately, the precise opposite of a fiscal expansion is also in the cards. There is another way I could be wrong about central banking omnipotence, omniscience and omnipresence.

The narrative goes like this: in 2000 we had the tech bubble. In 2008 we had the housing bubble. In 2017, what’s our bubble?

Is it a government bond bubble, perhaps? What if the European sovereign debt crisis was just the beginning? Like sub-prime was in 2006. What if our government is on the verge of going bankrupt?

IceCap Asset Management put it like this: “2000 tech bubble, estimated losses $5 trillion. 2008 housing bubble, estimated losses $15 trillion. 2017 government bond bubble, estimated losses $?? trillion.”

Government debt is enormous. And it’s managed a 35-year bull market. With yields at or near zero in both real and nominal terms, it has reached its logical end just about everywhere in the developed world.

If the government debt bubble bursts, it’ll be a very different crisis to the housing and tech bubble.

First of all, it’d be far, far bigger. But the differences go deeper. The tech and housing bubble’s crashes wiped out theoretical levels of wealth. It was wealth that only existed on paper in the first place. Unfortunately, the debt associated with the houses made the second crisis worse, but it was still asset based.

A government bond bubble leads to far deeper consequences. Government bonds are a promise to pay a fixed amount of cash on a fixed date. These supposedly risk-free assets tumbling in value and leaving financial firms under water is just the beginning.

If the government can’t borrow money at affordable rates, it can’t spend either. Government spending involves flows of money, such as welfare, healthcare and defence spending. If those fall, it’s not just the write-down of an asset, but a loss of income. GDP is impacted directly. As are basic government services.

In my opinion, this will not be allowed to happen. Central bankers will save the day and pick inflation over an insolvent government. That’s something you have to prepare for.

The question is how much pain the central bankers would allow in the government bond market before stepping in. After Lehman Brothers, I’d suggest not much. Negotiations with Greece were one thing. If a major economy’s government wobbles, the story will be different.

Still, it’s likely there will be some market turmoil before central bankers stage another rescue. The question is when this will break out.

Timing the government bond bubble’s bursting

Financial crises have come on the back of central bank rate hike cycles with remarkable reliability. That sounds obvious given central bankers move policy rates in reaction to the business cycle. But it also means a crisis without a rate hike cycle is unlikely. In other words, if you’re looking for a crisis, you probably have to wait for a rate hike cycle first.

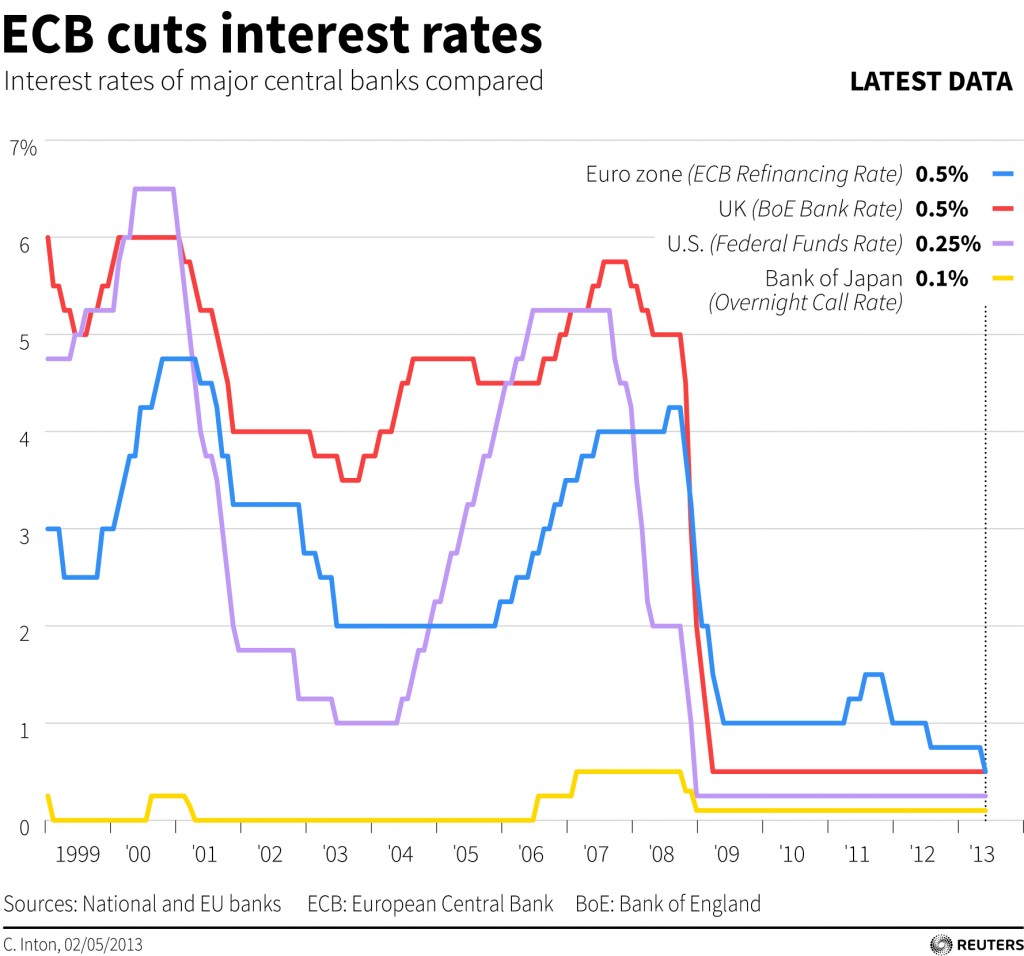

But it might not take much of a cycle this time around. Do you remember which years the European sovereign debt crisis was particularly bad? 2011 and 2012 were the key years. Any guesses which central bank was the only one to raise rates during that time? Only the European Central Bank (ECB):

The chart illustrates my points perfectly. Firstly, rate increases and financial market messes coincide. What’s different this time is that the rate increase required might be miniscule. The cycle could be a blip on the chart of long-term central bank interest rates.

Then again, moving the rate from 1% to 1.5% is a 50% increase! Not many governments around the world could stomach a 50% increase in interest expense without a problem. (The actual cost would filter through slowly over time, but could be priced into bonds much faster.)

By the way, the Bank of England is expected to double rates today…

So will we have a crashing bond market, or a booming expansion in government spending?

To figure out which way things will turn, the best man to talk to is Akhil Patel. His analysis of cycles and trends allows him to add timing to his forecasts. You can find out just what he’s predicting here. There’s a short-term and a long-term prediction. So whether you think a bond crash or government spending boom is more likely, you’ll only be half right. Unless you nail the timing using Akhil’s cycles methodology.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Related Articles:

- What are Central Bankers so worried about?

- How to predict the future, with double payback

- Diversification of death

Category: Central Banks