Today’s Capital & Conflict comes from the latest issue of The Price Report by investment director Tim Price.

Within my asset management business, we deal with two levels of emotional responses to the state of the financial markets.

At one level there is our own level of hope or fear. At the next level there is the hope or fear experienced by our clients.

While we may be completely relaxed about some of the investments we undertake, we also have to be mindful of what our clients might feel about those same investments. At the extreme, if clients are uncomfortable with what we buy for them as part of our discretionary practice, we risk losing them forever.

They don’t cover emotion in the financial textbooks. Which is odd, given that profound swings in emotion inevitably occur at market tops and bottoms, and those swings also create what, in the fullness of time, become tremendous buying (and selling) opportunities.

But then most of the financial textbooks are useless. As most modern economics is useless. Utterly unfit for purpose.

If this view seems a little extreme, don’t take my word for it. William White, the former chief economist for the Bank for International Settlements (the so-called central banks’ central bank), said the following last month:

“All the market indicators right now look very similar to what we saw before the Lehman crisis, but the lesson has somehow been forgotten.

“Central banks have been pouring more fuel on the fire. Should regulators really be congratulating themselves that the system is now safer? Nobody knows what is going to happen when they unwind QE [quantitative easing]. The markets had better be very careful because there are a lot of fracture points out there.

“Pharmaceutical companies are subject to laws forcing them to test for unintended consequences before they launch a drug, but central banks launched the huge social experiment of QE with carelessly little thought about the side-effects.”

Needless to say, I completely agree. (I recently published a warning on US and UK stock markets, which, regardless of the recent correction, still look massively overvalued. You can read it here.) QE was a leap into the unknown extremes of monetary policy experimentation, and yet central bankers conduct themselves with the confident demeanour of credentialed scientists, rather than the quacks they actually are.

Unusually for an economist, White has a habit of speaking his mind. Here, for example, is what he said during a previous moment of refreshing candour about his profession:

“The analytical underpinnings of what we [mainstream economists] do are actually pretty shaky. A reflection of that fact, is that virtually every aspect you can think of with respect to monetary policy, about best practice, has changed and changed repetitively over the course of the last 50 years. So, this stuff ain’t science.

“Think about what’s happened recently. One, it’s completely unprecedented. People are making it up as they go along. This is hardly science – building on the pillars of the past. Secondly, what they’ve been making up as they go along actually differs across central banks. The Bundesbank, for example, is invariably fighting the threat of high inflation, whereas the US Federal Reserve is more concerned about the prospect of deflation]. They can’t even agree amongst themselves about what’s the best way to do things. I’m becoming more and more convinced that all of the models we use are basically useless.

“The best way to look at the economy is as an ecosystem. Some live, some die. There is no equilibrium as such; things are constantly growing. It’s surprising that we’ve had this huge crisis that the mainstream didn’t predict. It’s gone on for years, which the mainstream absolutely didn’t predict. I would have thought this was a basis for a fundamental rethink about what we used to think we believed. But that hasn’t happened. The policies that we’ve followed – on the monetary side at least – since 2007 are just more of the same. Demand-stimulating policies that we’ve been following, I think, erroneously, for the last 30 years.

“We’ve got the potential to do so much harm by not getting the creation of fiat credit and money right. We’ve got the capacity to do so much harm that we should be focusing much more on making sure that doesn’t happen.”

Faced with the full ferocity of the global financial crisis in 2008, our politicians and central bankers had an opportunity to reset the system, and to allow capital to flow from weak hands (bad banks) to strong hands (better banks, and more entrepreneurial businesses). They did not take that opportunity. Instead, markets got hosed with ever cheaper torrents of money as part of the QE process. Interest rates were driven down to rock-bottom levels – and in some cases below even that. The can was kicked down the road. Now our central banks have run out of road, and that is a real problem.

I always expected a Fed chair to get carried out of his (or more recently, her) office on a tide of market vengeance. But incredibly, Alan Greenspan, the original architect of central bank intervention, left the Marriner Eccles building like some kind of conquering hero. I then hoped that natural justice would catch up with his successor, Ben Bernanke. But no, “the Ben Bernank” survived too. And then Janet Yellen after him. But it does now look as if poor Jay Powell is going to be the patsy on whose shift the whole sucker finally goes down.

In line with the world’s other major central banks, including our own Bank of England, the Fed is now in a desperate bind. On the one hand, it has made it abundantly clear that it intends to normalise (ie, raise) interest rates. On the other hand, the financial markets are now distinctly fragile and, like Pavlov’s dogs, traders are baying for more help in order to shore up those markets. They would prefer to see interest rates cut, and also to get the chance to scarf down a few more trillion dollars of easy money. But if the Fed were to cut interest rates now or shortly in the face of growing trader angst, let alone reintroduce QE, it would lose what fragment of credibility it now retains – and that has implications for, among other things, confidence in the currency system, bond yields, and so on. If you were looking for directions in getting out of this mess, you certainly wouldn’t start from here.

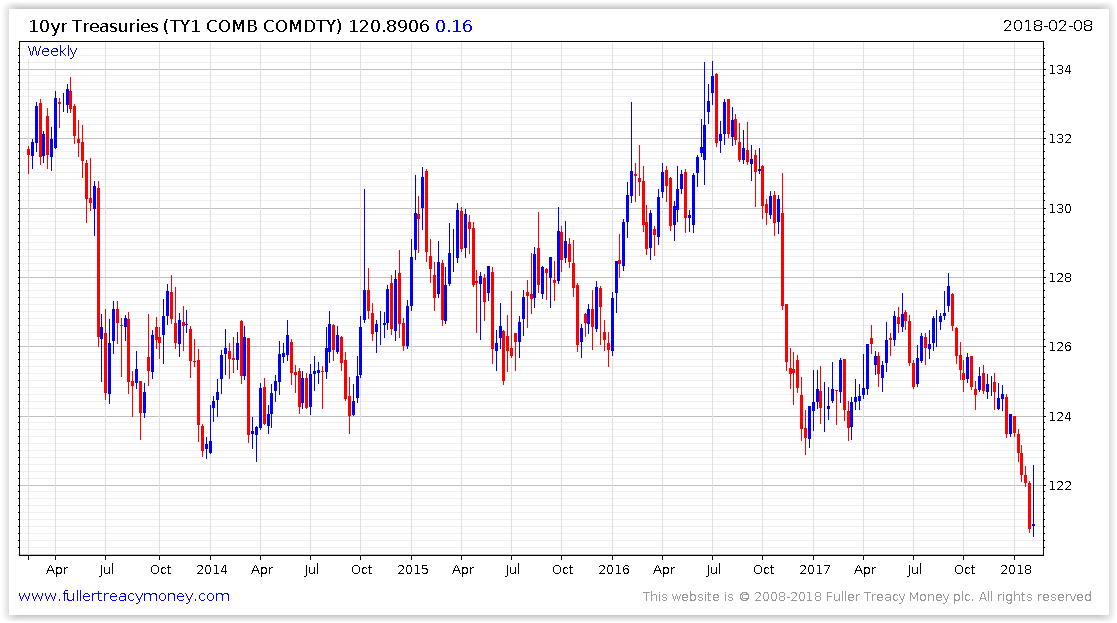

Yields on long-term US government bonds have now risen to four-year highs as investors fret about economic growth and the prospect of rising inflation. Given how derisory bond yields still are, this is why I elected to liquidate our last remaining bond investments in The Price Report portfolio [N.B. Tim has also removed bonds from the London Investment Alert portfolio]. It’s still possible that a deflationary scare could see a temporary reduction in bond yields from here, but the bond markets as a whole are so overpriced that the prevailing risks are all to the downside. Anybody aggressively buying bonds at current levels is picking up nickels in front of a very fast steamroller.

You can see how the bond market disintegration is occurring on the following chart, which shows recent price declines in the ten-year US Treasury bond futures contract:

Ten-year US Treasury futures, last five years

Having reached a high of 134 during the summer of 2016, the contract is now trading at 122. In bond markets, a loss of over 10% is big news. And as I’ve pointed out on numerous occasions, what happens in the bond market matters, because the market for bonds dwarfs the market for stocks. Declining bond markets will inevitably impact equity markets, and probably not for the better. Prices in all things are relative, after all. All markets are ultimately a competition for capital. So when bonds cheapen, especially when they do so dramatically, expect stocks to cheapen too.

It’s still too early to say whether the weakness on display in global stockmarkets two weeks ago is a precursor to a major crash, or merely signs of investor skittishness, albeit on a significant scale. One thing that is worth pointing out is that a number of markets are tending to mirror price action in the US – which is a sign that investors globally are panicking, and, as ever, looking for North America to lead the way. (This may also mean that some foreign markets are trading off purely because of sentiment, and not because of fundamentals.)

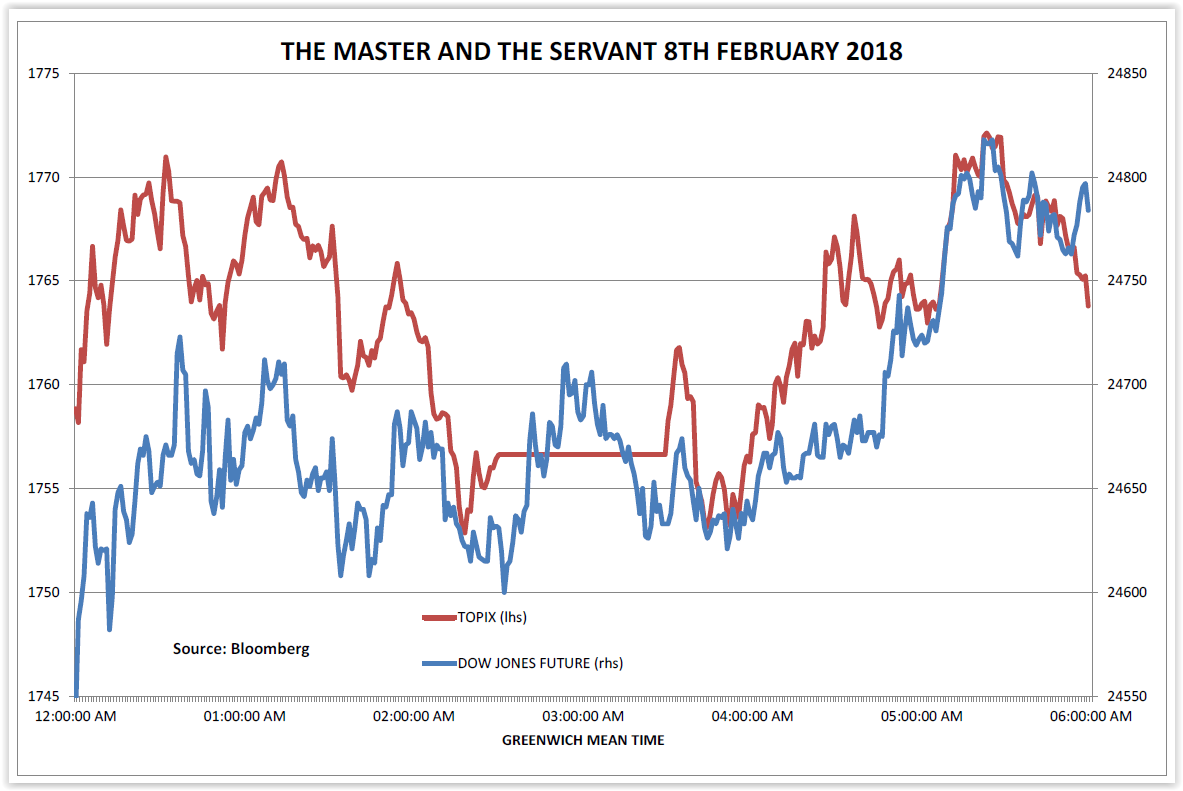

My friend Jonathan Allum, for example, makes the following joke. Q: What’s the difference between the Japanese stockmarket and a supermarket trolley? A: A supermarket trolley has a mind of his own. He cites the way that Japan’s Topix (in red in the chart below) is just meekly trotting behind the course laid out by the US Dow Jones Future (in blue):

Source: SMBC Nikko Capital Markets Ltd

Source: SMBC Nikko Capital Markets Ltd

As Jonathan goes on to say,

The parallels with early 2016 are intriguing. Whilst most commentators stress the similarities between the recent market rout/collapse/turmoil (choose excessively melodramatic description of your choice) and 2007-9, it is worth noting that as things stand – and I accept that things may not stand still – the global falls we have seen this month (and this is not true of all markets) have been less marked than we saw two years ago.

This is certainly true in Japan. In the first two weeks of February 2016, the TOPIX index fell 16.5% – so far this month it is off 6.1%. There are, I suspect, two reasons why the media ignores the parallels with the events of two years ago. Firstly, it is because they ignored the 2016 correction at the time. Whilst financial markets are all over the front pages this time around, they were very much restricted to the City sections two years ago.

Secondly, the 2016 correction didn’t lead anywhere and doesn’t support the sort of financial Armageddon story in which so many pundits delight. It was one of the “false positives” so often thrown up by the markets. As Paul Samuelson famously observed, way back in the 1960s, the stock market has predicted nine out of the last five recessions.

To put it another way, while I’m very concerned about the technical breakdown in US stockmarkets, I’m much less concerned about the weakness being displayed in Japan – not least because the Japanese market is trading on altogether more attractive valuations, whereas the US remains horribly expensive on any historical analysis.

So all markets are not created equal, but when the proverbial hits the fan, as it did last week, all things tend to correlate towards a level of 1 on the way down. This will be an opportunity, in other words, for investors who missed out on the Japanese rally the first time round to get back in again relatively cheaply.

There’s another reason why I’m relatively sanguine about the current heightened stockmarket volatility. I don’t believe in market timing, and I certainly can’t do it with any success, so my investment approach is always to be more or less fully invested, albeit across a wide variety of weakly correlated assets, and also to focus my equity exposure on the most defensive, value-oriented stocks or funds I can find.

A couple of weeks ago I had the opportunity of listening to an update from Greg Fisher (manager of the Halley Asian Prosperity Fund, the best performing equity vehicle in the entire The Price Report portfolio). Asian Prosperity Fund has returned 151.4% in GBP since inception in November 2012, the equivalent of a compound annual return of 19.9%. What’s fascinating, though, is that the overall metrics of Fisher’s fund are more or less identical to what they were when it was launched five years ago.

What this suggests to me is that Asia (especially Japan and Vietnam) is not expensive, and that one should discriminate between markets that look expensive simply because they have risen of late, and markets that are expensive because their underlying valuations are extremely rich. Asia is the former; the US is the latter. Read my letter to UK stockmarket investors here to get the full picture.

Until next time,

Tim Price

Investment Director, The Price Report

Category: Central Banks