Take a moment to think about the following phrase: “risk-free rate of return”.

It’s part of the everyday language of finance – one of those terms bandied about so much that we rarely stop to think about what it actually means.

It serves as the interest rate which an investor should receive from an investment that bears no risk.

Of course, in reality, it doesn’t exist. Even the safest assets bear a tiny amount of risk. But it’s inconvenient to use the term “almost completely risk-free rate”, so we shorten it.

And for lenders around the world, the risk-free rate serves as the benchmark which other rates are priced against.

Assets offering a “risk-free rate” of return are typically government bonds – US Treasury bills or gilts, for the UK equivalent.

The fact they’re “risk free” mean they’re viewed as “safe havens” – the kind of assets that will protect your portfolio in times of volatility.

In many ways it makes sense. Unlike the millions of companies that will go bust due to coronavirus this year, people borrowing from the government can feel fairly comfortable that they will be paid back.

A risk-free rate or a return-free risk?

But can we really view government bonds – at least those issued by developed economies – as risk free?

Let’s take a look at the Investopedia definition of a safe haven asset:

A safe haven is an investment that is expected to retain or increase in value during times of market turbulence. Safe havens are sought by investors to limit their exposure to losses in the event of market downturns.

And by this definition, gilts and US Treasury bills have retained their definition of safe havens – sort of. They’re highly liquid, there’s strong demand for them, and they are often negatively correlated to, say, the stockmarket, at least many people think they are. In the secondary market, they’re trading at a premium.

But coronavirus has turned things on its head.

When much of the world went into lockdown back in March, investors piled into government debt.

Sky-high demand has been pushing yields through the floor.

In January, ten-year UK gilt yields were around 0.75%. Now, they’re lingering around 0.2%. Similarly, ten-year US Treasury bills have dropped from around 1.6% in January to around 0.75% today.

Once you factor in inflation, that puts the yield on a lot of government debt in the red.

In short, with rates already at all-time lows, inflation creates negative real returns.

They could soon go even lower too.

And that’s not just because a second wave could send panicky investors scrambling to the supposed safety of government bonds.

Just a couple of weeks ago, the Bank of England’s deputy governor wrote to banks asking how they would prepare for rates to dip below zero. Yields are below zero on swathes of debt anyway, but the deputy governor’s enquiry isn’t great news for bondholders.

Negative rates could be a kick in the teeth for the FTSE 100 too. Unsurprisingly, negative rates tend to squeeze banks’ profitability, and banks make up a hefty chunk of the FTSE 100’s market cap.

Even inflation-linked bonds are looking vulnerable.

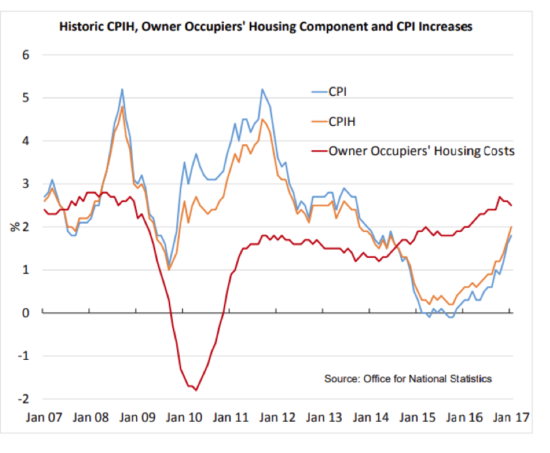

It looks increasingly likely that the government will go ahead with its plan to scrap the retail price index (RPI) and bring it in line with other indices, such as the consumer price index including housing costs (CPIH).

It’s a way for the government to save taxpayers money, as it can borrow more cheaply. But for bondholders, it means lower yields.

Holders of inflation-linked bonds aren’t exactly adrenalin junkies either – one of their biggest buyers are pension funds, as they promise to future-proof returns.

It’s not uncommon for pension funds and other institutional investors to be forced to hold assets such as gilts. Even if they’re paying through the nose to buy them, their mandates often require them to hold a certain amount of “safe” assets.

But for the average person, the idea of paying for the privilege of funding the government isn’t a great draw.

But is it worth taking the hit anyway? If government debt is the closest thing to “risk free” that an investor can get, then does it justify holding a proportion in bonds anyway?

After all, inflation is persistently low, right?

Take a look at the graph below.

Source: Office for National Statistics

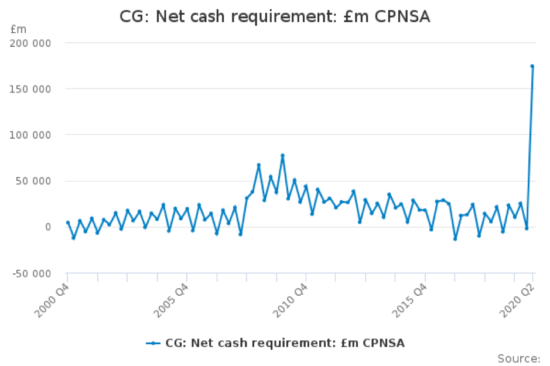

Source: Office for National Statistics

Government debt is on the up. In H1 2020, government borrowing smashed its previous record by nearly three times, with its cash requirement reaching £246 billion.

In fact, the government is on course to raise more than double the amount it raised during the financial crisis.

And with the onset of local lockdowns across swathes of the UK, it doesn’t look like the chancellor is about to put down his chequebook yet either.

So how can the government even begin to chip away at its mountain of debt?

There’s only one way, and it’s not good for bonds.

I am, of course, talking about inflation.

All the best,

Nathan Tipping

Research Analyst, Southbank Investment Research

Category: Central Banks