The butterfly effect explains how a fluttering of little wings can trigger a hurricane on the other side of the world.

Central bankers have been fluttering their little fingertips over the “0” key, generating trillions in digital money. Today, we go storm hunting to try and find the disturbing results around the world.

The first consequence is obvious. Central bankers have bought up vast swathes of government bonds, pushing up prices and pushing down interest rates.

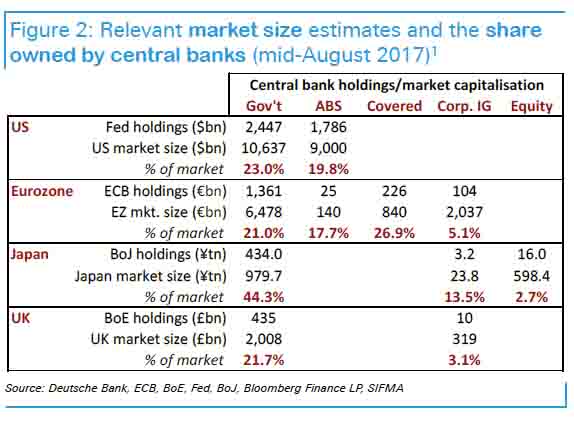

But they also bought corporate bonds, asset-backed securities and stocks. This chart summarises which major central banks bought what:

The result is record low bond yields, record high stockmarkets and record low spreads between government bonds and corporate bonds of various levels of risk. In other words, everything went up. (Except the Aussie stockmarket, where there was no quantitative easing (QE), and still no record high…)

In Europe, the sovereign bond buying has been most interesting. The European Central Bank (ECB) is constrained by more rules than its counterparts around the world. And it presides over multiple governments. Put the two together and you get uneven purchases of government bonds. That in turn benefits countries unevenly.

The Germans have benefited greatly

With their vast amount of bonds and higher credit rating, the ECB has mopped up the bund market while implementing QE. Smaller countries with worse ratings haven’t gotten the same boost. A great example of how EU rules make those countries grumpy about the implicit German favouritism.

But lately, the ECB has run out of German bunds to buy. In fact, there isn’t much left to buy in Europe if they stick to the rules. QE may have hit a legal limit. But laws can be changed.

Over in the private sector, low interest rates have done nothing less than revived the dead. Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s credit strategists put together a report called “The rise of the Zombies” which researches the number of zombie companies.

These are companies that can only pay off their debts thanks to extraordinarily low interest rates. The analysts put the figure at 9% of non-financial companies in Europe’s Stoxx 600 index. That’s almost double the 2013 amount.

A huge backlog of corporate failures that haven’t happened

Rupal Bhansali from the fund managing company Ariel explained on CNBC that these firms can’t actually make the interest payments, it’s just that they are capable of delaying the reckoning thanks to the extremely cheap credit they can access.

Outside companies listed on the stock exchange, between 20% and 30% of small and medium-sized companies are suspected to be zombies in the UK, EU and US according to the ECB.

Eoin Murray, head of investment at Hermes Investment Management, explained it all beautifully: “Like animals in captivity, companies incubated on the milk of QE and low rates may no longer exhibit the natural behaviours needed for success in the wild of a stimulus-free market.”

The Telegraph explains how this will look for UK businesses:

More than 448,000 companies were in trouble at the end of September, up 27pc on last year, according to research by business recovery specialist Begbies Traynor.

Julie Palmer, a partner at Begbies Traynor, said businesses had taken “too many risks after being lulled into a false sense of security” by low interest rates.

The world’s companies are on an interest rate knife-edge

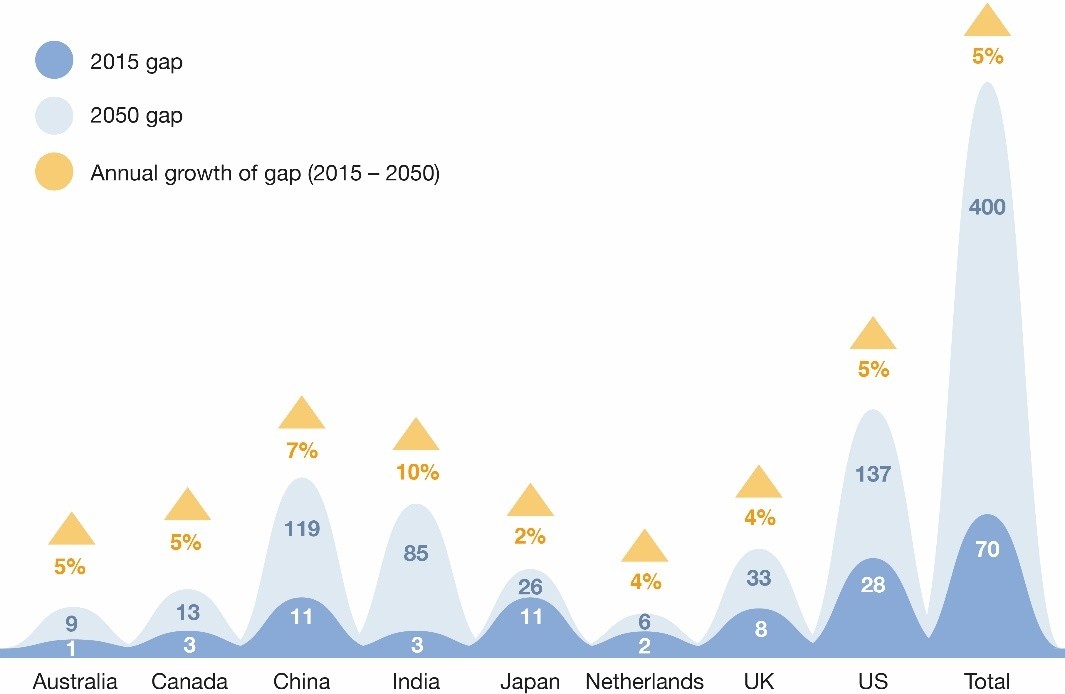

Retirees and pension funds are being squeezed by low interest rates too, in a different way. They had assumed returns between 5% and 8% a year thanks to academics’ promises. But interest rates tumbled, crushing the returns of safe-haven assets. The result is a shortfall measured in the trillions of US dollars, and growing very rapidly:

Source: World Economic Forum

Now that we’ve stacked up the consequences of central bank action, let’s examine what a return to normal would mean. If the concept of “mean reversion” holds and interest rates, stockmarket valuations, bond spreads and everything else the central bankers have fudged return to normal, what would our world look like?

Financial zombie apocalypse

Normal interest rates would sink entire governments. Currently, the euro area governments use 5% of their tax revenue to pay for interest expense. Many have yields at or close to 0%. Interest bills could double or triple or more if rates go back to normal, bringing interest expense above the 1980s highs of 10%. Combine this with falling tax revenue and rising government spending and you get dangerous maths.

Tim Price explains just how fragile our British government is here.

But it’s not just rising interest rates that are a threat. Here in the UK, even inflation won’t rescue the government from its vast debts. Historically, debt could be inflated away into meaningless denominations. But these days, governments often borrow using inflation protected bonds. More than a third of UK government gilts are inflation indexed. So as inflation rises, the interest expense goes up with it.

This is a wonderful example of how hubris gets you into trouble in financial markets. Thinking the Bank of England had inflation figured, the Treasury reconfigured its borrowing habits. Now they’ll have to pay the price for faith in central bankers.

What about the private sector?

Low interest rates have backed up a vast amount of company failures, job losses and economic pain. Raising rates could trigger the lot, including the failure of about 250,000 zombie companies in the UK alone.

How many of the world’s companies will be forced to raise equity, refinance at rates that destroy profitability, or declare bankruptcy when rates rise? As those firms go down, their partners will too. Then the funds that invest in them.

The new-found importance of central bankers has created a political mess too. Suddenly, monetary policy, exchange rates and the euro are hot topics in political races. Already the issue has made itself felt in elections this year.

Next year, the Italian election risks turning into an anti-euro referendum, if it isn’t already. Ironically enough, the ECB is planning on halving its QE programme just when the Italians decide on whether to support anti-euro parties. If it turns out they can’t withdraw, the painful consequences of trying will coincide with the election. Having the ECB trigger economic chaos isn’t encouraging for euro enthusiasts.

Higher contributions from companies and governments to keep pension funds funded are already squeezing budgets. The problem is even causing trouble in paradise. Maui County in Hawaii is pushing up taxes to try and deal with a 50% increase in mandated pension contributions. The major pension systems of the world will be more than $200 trillion short by 2050. Good luck raising the funds…

Altogether, a world with normal inflation and normal interest rates looks like a financial zombie apocalypse. It’s the impossibility of normality.

The solution is to go camping

The horrific outcomes of a world returning to normal puts you in one of three camps. The first is an actual campsite, where you plan to wait out the financial apocalypse.

The second option is to predict that central bankers will never allow the world to return to normal. They’ll maintain QE and low interest rates. They’ll do “whatever it takes”, as Mario Draghi once said, to maintain the status quo.

The third option is that the world’s decision-makers will push the reset button on the whole system. Your financial wealth is only accounting entries after all. If someone can’t handle their liability side of the balance sheet, they can just strike off someone else’s asset side. That’s what happened to Lehman Brothers’ creditors.

Bitcoin’s biggest profits

Yesterday we took a look at bitcoin arbitrage opportunities. As ever, Sam Volkering was on the case before me. Here’s his explanation for why the bitcoin price is different in different places:

So the thing with these price differentials (like in Zimbabwe) is that, in most jurisdictions, to actually get into bitcoin (from fiat money), you need to purchase through an exchange typically in that jurisdiction, which most often requires some form of identification.

Thus you find that someone in Zimbabwe typically can’t set up an account with Coinbase unless they can get access to UK/US/Australia etc. payment card and a VPN (which disguises their location). Likewise I can’t set up a US-based exchange account unless I’ve got US ID and a US payment card and then set up my VPN for the US. But I can set up a UK and Aussie one and regularly buy in both markets. The downside is more stable countries like the UK and Australia don’t display that arbitrage opportunity.

But you are correct in saying this is a huge arbitrage opportunity if you know how to work it. In fact I’ve utilised this before in other crypto thanks to arbitrage existing between crypto exchanges for particular crypto. The other difficulty though can be the speed at which you need to move around the blockchains. That can decrease the arbitrage opportunity.

I actually wrote about this in a Revolutionary Tech Investor weekly update from 14 June this year. If you track that down you can read about my crypto arbitrage experience.

But there is consistently plenty of arbitrage opportunity in crypto markets if you know how to move about and in and around exchanges – and if you can have open fiat-to-crypto accounts in multiple jurisdictions.

You can check out Sam’s cryptocurrency work here. He takes you through which cryptos to buy, avoid and more.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Related Articles:

- Bitcoin offers you a holiday in South Korea

- The return of currency competition

- Were you a “crypto” believer in 2014?

Category: Central Banks