Today we ask ourselves who you’d rather have as your fund manager. There are two options to choose from.

The first is Herbert Stein, an American economist who chaired the Council of Economic Advisers under Nixon and was on the board of The Wall Street Journal. His law, known as Stein’s Law, forms the basis of the Stein Fund: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

Stein applied this to America’s balance of payments deficit during his time in the halls of power. That’s still going strong, ironically. Although the Americans had to abandon the gold standard to achieve their continued run.

The other fund management option is Murphy, of the famed Murphy’s Law: “Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong.”

Both the Murphy Fund and Stein Fund have had a rough time recently. Apart from the plunge of Tesla, their only successful trade since the European sovereign debt crisis was the Shenzhen small-cap stock index, which fell more than 5% yesterday. That could be a canary in the coalmine for the rest of China’s market, but few Chinese shareholders seem to think so thus far.

The good news for the Murphy and Stein funds is that the odds are stacking up in favour of both. There are plenty of things which could go wrong, and many trends that are unsustainable.

One of the biggest holdings in both funds is a bet on Greece’s and Argentina’s new bonds. These are quite comical.

Betting on bailouts

Greece is hoping to issue its first bonds in three years in the coming week. They’re expected to yield less than 5% according to the Financial Times’ sources.

That’s a bit misleading though. The country is actually issuing short-term bonds known as “bills” anyway. Because they expire within weeks, they’re seen as a lot less risky than a five-year bond. Hence the yield is just 2.33%. When it’s paying that level of interest, you’d think Greece is doing just fine.

But it isn’t. Greece is only doing OK because it has an entire pipeline of bailouts slowly making their way through the International Monetary Fund (IMF), European Central Bank and EU bureaucracies. A bet on Greek bonds is a bet on the political will of those institutions (none of whom are terribly accountable to anyone, so it’s a good bet).

After three bailouts in seven years, another bailout is probably a fair assumption. But what’s important to keep in mind is that the Greek debt is on an unsustainable, even “explosive” path according to the IMF. And that at incredibly low yields.

Stein’s Law is clear. Greece cannot go on like this forever. It must stop.

The Greek effort is probably inspired by the lunacy of the Argentines. They’ve issued 100-year bonds at 8%.

100-year bonds? Argentina is the world champion of bond defaults and a top-ranked competitor in hyperinflation. What could possibly go wrong within 100 years? Ask analysts at the Murphy Fund.

Greece’s reliance on continual bailouts has inspired the European banking sector. With three banks bailed out in the last few months, the eurozone’s banks have surged on the stockmarket. But an industry that relies on bailouts can hardly be deemed successful.

The debt drug is everywhere

Next up on Stein’s and Murphy’s punts we have the entire higher education sector. NatWest estimates that more than two thirds of UK students will never pay off their loans. Instead, they’ll make repayments for 30 years before writing off the balance. That’s something to look forward to…

Over in the US, the problems exposed in subprime lending also feature in student loans. With a default rate around 40%, former students are finding their incomes and welfare cheques cut by court-enforced loan repayments. Usually the students don’t show up to court. But those who do all too often discover the owner of their loan can’t actually prove they own the loan.

It sounds odd, but the same phenomenon dominated the subprime securitisation story. Loans were sold off and repackaged so many times that the paperwork trail broke down somewhere.

When you’re an investment banker, a loan is nothing more than a cashflow. The legalities of mortgage and property law get lost. And so many American students are defaulting on their loans without consequence because the owner of the loan can’t conclusively prove they do own it with the correct paperwork. Once they fail, the loan is erased.

Is it common? The New York Times adds evidence:

Nancy Thompson, a lawyer in Des Moines, represented students in at least 30 cases brought by National Collegiate in the past few years. All were dismissed before trial except three. Of those, Ms. Thompson won two and lost one, according to her records. In every case, the paperwork Transworld submitted to the court had critical omissions or flaws, she said.

The beauty here is if this story gets out and goes viral

If US students realise they might not have to repay their student loans… well you’ve got subprime all over again. And the figures are big enough for even the likes of Ben Bernanke to get worried about. Studentloanhero.com summarises the numbers:

You’ve probably heard the statistics: Americans owe over $1.4 trillion in student loan debt, spread out among about 44 million borrowers. That’s about $620 billion more than the total U.S. credit card debt. In fact, the average Class of 2016 graduate has $37,172 in student loan debt, up six percent from last year.

Of course, there’s a reason people are defaulting on their student loans in the first place. Their education didn’t lead to an income.

In Australia, there’s a similar problem with documentation in the mortgage sector. In 2006, the Supreme Court of New South Wales ruled that borrowers who had their loan application manipulated by their mortgage broker could get their loan cancelled. According to my PhD research, rather a lot of mortgages feature such manipulation. Denise Brailey is the Nancy Thompson of Australian mortgages, getting huge loans cancelled consistently.

Believe it or not, when Argentina defaulted on its bonds in 2014, there was a selection of bonds which nobody could find the paperwork for.

The bonds seem to have vanished

The lack of ownership proof tells you a lot about the culture of debt and lending. If these people can’t even prove ownership, do you think they give much thought to whether the loan is affordable?

Over in the stockmarket we also have a debt-financed boom. Usually this is hidden in plain sight – margin lending. This is when brokerages lend to their customers to buy shares. Usually the shares return more than the loan costs.

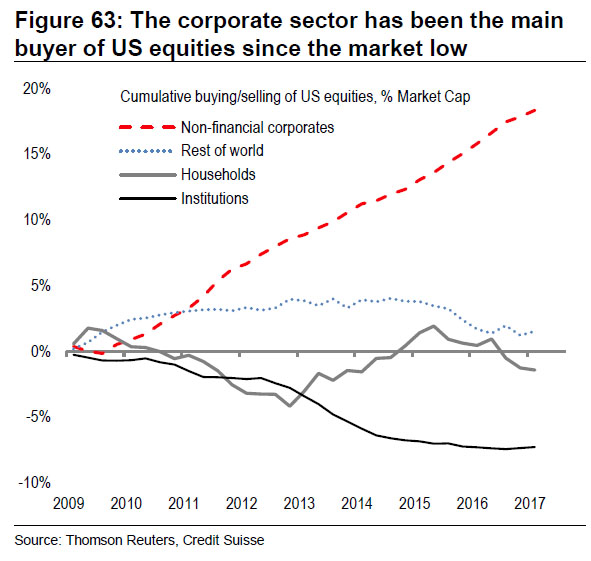

But margin lending isn’t booming. Instead, it’s company buybacks that are surging. Companies are borrowing near 0% rates and buying their own shares. Here’s Credit Suisse’s chart illustrating how companies are the ones buying stocks:

How much of the stockmarket’s boom comes down to debt-financed buybacks? What happens when companies stop buying?

There’s a more important question to ask.

What do all these things have in common?

Debt.

All these stories are really just parts of a bigger picture. It’s quite simple. Every part of our life is now debt dependent. Our education is debt financed. Our day-to-day spending is on a credit card. The companies we work for are debt financed. The home we live in needs a mortgage to be affordable. The cars, furniture and TVs we buy come with consumer debt. Our investments go up or down based on borrowings too.

That needn’t be a bad thing. It’s allowed us to reach the outrageous living standards we have today.

The problem arises when new borrowing is needed to repay debt. I don’t mean rolling over your debts. Companies, in a bid to maintain a steady amount of leverage, will borrow new funds to repay the old. That needn’t be an issue – it enhances returns to the shareholders in a sustainable way. It makes otherwise uneconomical activities worthwhile in this way.

But these days our entire economic growth is dependent on the level of debt growth. One man’s borrowings is all that allows another man to repay. That’s why interest rates are the be all and end all of the economy – they’re the price of debt. It’ the only price that matters anymore.

Murphy and Stein will return with a vengeance

A debt boom comes under Stein’s Law. It can’t continue indefinitely, especially not at this pace. Murphy chimes in – something will go wrong.

Plenty of societies have faced the end of debt booms. Britain has too. It had to go to the IMF, hat in hand, in the 60s and 70s. Although the solution back then was, ironically, a loan.

At the end of a debt boom, there’s usually some sort of “reset” rather than a collapse. But that’s another story.

The one I want to highlight today began many years ago with the book Empire of Debt. It was my first introduction to the ideas you read about here at Capital & Conflict. The book was written by the founders of the company which publishes this newsletter. That company grew into an enormous network of analysts and subscribers.

And now the company’s legacy has come to a head here in Britain. It’s a bigger culmination than our predictions of the financial crisis and sovereign debt crisis years ago.

In coming days, an email about the very future of Britain will hit your inbox. I’ve tried to give you the backdrop today so the ideas in that email aren’t too shocking. I hope you won’t be put off by the brash honesty. It’s what helped so many of our subscribers avoid disaster in the past.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: Central Banks