Today’s Capital & Conflict is about the biggest change to the world economy in ten years. It’s happening slowly. But it will be the sea change that sets the scene for the next ten years of investing.

The government doesn’t control many prices in our economy any more. Here in the UK it used to determine exchange rates, electricity prices and wages, for example.

We now understand why it’s a bad idea to use price controls. It stops the supply and demand effect from solving the problem, and it creates shortages and surpluses of whatever the government is controlling.

There aren’t many places left where the government still meddles directly in prices. Rent control still exists in some places, causing all sorts of trouble like property shortages and dilapidation.

But there is one place the government still rules the roost – monetary policy. The government still controls the price of debt. The central banks of the world move the interest rates up and down when they feel like it. For some strange reason, economists haven’t figured out that this causes the very same sorts of problems as price controls do everywhere else.

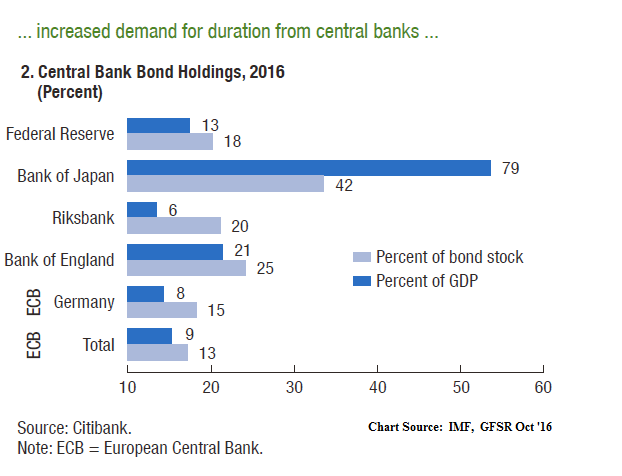

The thing is, the central bankers are completely out of control at this point. Central banks have been so busy buying debt over the past decade they’ve accumulated an incredible stock. This chart from Citibank shows just how much of their own government’s bonds several central banks now own. And the same number as a percentage of their national GDP.

The Bank of England is right up there with 25% of British GDP. That’s no surprise given the size of our financial sector relative to the economy. But it’s still a remarkable amount.

Until now, this ravenous appetite has been about keeping the economy alive. It’s intensive care though. By pumping cash into the banking system and taking bonds out of it in return, the central banks aim to make the banking system safer and thereby lend more. Banks can lend cash to you, not bonds.

There are a few interesting reason why that hasn’t worked well. There’s no shortage of cash to begin with. Banks are parking the cash they get back at the central bank, where it earns plenty of interest.

Cash and bonds are considered to be very similar in the financial world. The risk and return of bonds is incredibly low, next to cash’s zero for both. So the actual change to banks has been small despite the huge purchase of bonds.

That’s all background information. Here’s the key point for today’s Capital & Conflict: the story is beginning to reverse. Central banks are looking into selling bonds for cash. At least one of them is.

The worm turns

In the first four months of 2017, central banks have bought a trillion USD of investments, especially bonds. That’s according to a new research report from Bank of America. It’s a record amount.

But the makeup of who is buying what has changed. The US Federal Reserve has stopped. The European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan have still been very busy.

The European Central Bank and Bank of Japan’s recent activity has masked that the Federal Reserve is turning the worm. Others will follow. If, or when, central banks on the whole start to reverse their policies, all sorts of new phenomenon could begin.

Just as the last eight years featured a bull market driven by central banks pumping cash into the economy, the next period will be driven by central banks doing the opposite. But what will that mean for investments?

Bond yields should go up as the central banker’s insatiable demand for bonds turns into supply. Higher yields mean lower bond prices. Can governments afford higher interest rates? Can mortgage payers? Who will buy the central bankers’ bonds? What will happen to the funds which own government bonds as their prices fall?

There could be a crash in the bond market. More and more traders are betting on it.

But it’s not that simple. Remember how cash and government bonds are considered incredibly similar? Economist Manmohan Singh reckons the Federal Reserve’s reversal will actually have a stimulus effect, not a tightening one. His argument is that, in many cases, bonds are actually more useful than cash if you want to stimulate lending. The odd mechanics of the financial system use government bonds as collateral in financial relationships. Central banks have bought so many bonds it’s pumped up prices and created a shortage. A lack of collateral at reasonable prices means less financial relationships.

Imagine you have a financial relationship with someone. It doesn’t matter what it is. Part of the agreement is that, if they default on the deal in some way, you get their government bonds to compensate you. In this way, those bonds are used as collateral and they reduce the risk of that transaction a lot. Worst case, you end up owning the bonds.

The unique thing about this is that two people have a claim on the same bonds. The real owner and the person who holds them as collateral. Just as both you and your bank have an ownership claim on a mortgaged house. Both benefit from the lower risk. Only when something goes wrong does the ownership solidify one way or the other.

Because the reversal of the central banks’ monetary policy means sending government bonds back into the economy, the collateral effect might boost the financial sector’s activity.

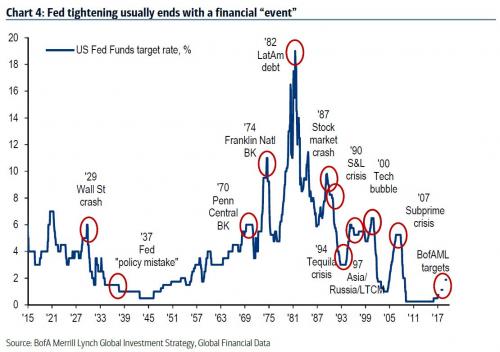

What of the investment implications of all this? Where this ends might be very simple. Look at the last 30 years. Each time the Federal Reserve raises interest rates, it ends in some sort of crash or crisis. More importantly, the height of each interest rate peak has been steadily falling since the 1980s.

The Federal Reserve won’t have to do much this time around before the financial sector is due for another crash. The forecast interest rate increases are big and fast. Look out!

It’s not only debt though

There’s something new to this cycle. The voracious appetite for government bonds is so big, and it’s swallowed such a big proportion of the bond markets, that central banks began buying other investments. The Bank of Japan, for example, has been buying vast amounts of stockmarket exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

So this time it’s not just government bonds that the world’s central banks would be selling, but other investments too. Central banks determine the future of almost all financial assets directly these days, not just indirectly. Perhaps that holds the key to the stockmarket’s future. More on that tomorrow.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: Central Banks