Yesterday we looked into stocks. But they’re a sideshow. The financial world really runs on debt.

Bonds are the main event. Bond markets are twice the size of stockmarkets. The survival of governments, giant corporates and pensions funds depends on bond values. A plunge is usually followed by default. And default means chaos.

Whether it’s Venezuela, Greece or Enron, it’s bonds that make or break countries and companies.

The thing is, bonds have been surfing a gigantic wave of prosperity. They just went through the biggest bond bull market, probably of all time.

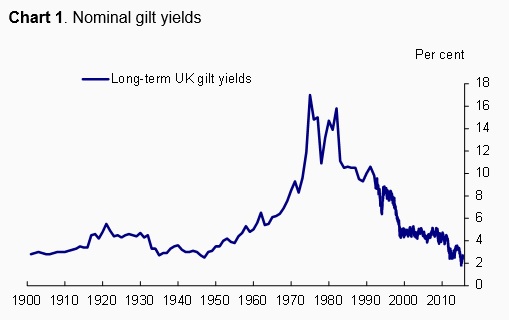

UK government bonds, known as gilts, surged in price as their yields tumbled. It’s the same elsewhere in the world. While governments and companies had to pay less and less interest, bond owners made more and more capital gains. It’s been that way for almost 50 years!

Source: Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2015, Bloomberg and Bank Calculations

Source: Barclays Equity Gilt Study 2015, Bloomberg and Bank Calculations

The only problem is, what if things go the other way? What if the epic tailwind turns into a headwind?

If interest rates rise, bond prices will tumble. Governments and companies around the world will see their interest bills surge. Pension funds will see the value of their holdings fall. Banks will cop both problems.

Remember, rising interest rates were what triggered the sub-prime debacle. They’re what triggered the European sovereign debt crisis too. And Britain’s mess in the 1970s. More on that below.

But what if rising rates happen on a systemic level – to all governments and companies around the world at the same time?

A bull market in interest rates means a bear market in everything else. Anyone with debt will be in trouble. And after a 50-year downward trend in interest rates, everyone has been sucked into borrowing.

But what might make interest rates and yields rise?

The coming bull market in interest rates

In his 2004 biography, Bill Gross was called the Bond King. He oversaw $2 trillion dollars in assets at his ginormous bond investment firm PIMCO at one point.

Yesterday he declared the bull market in bonds over. “Bond bear market confirmed,” the King told Twitter. Interest rates and yields are going to rise.

American rates have already moved up to a nine-month high. Governments around the world are lining up a wave of debt issuance. Central banks are planning to sell their vast holdings, slowly but surely, as they reverse quantitative easing (QE). Pension funds are selling holdings to pay out retirement promises.

That’s the supply side. What about the demand side? Who is going to buy bonds?

I can’t really think of anyone… Not at these prices.

If rates begin an upward cycle, bonds become about their yields instead of the capital gain. Until now, bondholders have slept well in the knowledge their bonds will probably be worth more tomorrow. They can sell out as and when they need. So government bond markets were a place for safe keeping. Safer than banks because governments can print money – they need never default.

But if prices fall over time, then buying bonds only makes sense if you’re holding to maturity. That’s the day the loan is paid back in full, no matter what’s happened to the price in the meantime. And your return then becomes the interest rate or yield.

Selling out early in a bond bear market means a capital loss. So investing in bonds with the plan to sell out no longer makes sense.

In this scenario, the pitiful yields make holding bonds a bad idea. Many governments have negative yields on their bonds once you factor in inflation. It makes no sense to hold them if you’re banking on a loss.

Once the power of a bear market dawns on this generation of bond investors, people will sell out and stop buying. It’s already begun according to one trader on Bloomberg:

“We’re seeing a lot of overseas buyers who would come in every time we’d have a move close to these levels who aren’t coming in anymore,” said Michael Franzese, New York-based head of fixed-income trading at MCAP LLC, a broker-dealer. “That’s kind of scaring me a little bit. One eye is constantly on the exit button.”

If the last bond bear market is anything to go by, you need to be seriously worried. The 70s were not a good time for Britain.

The 70s showed why rates, not debt matter

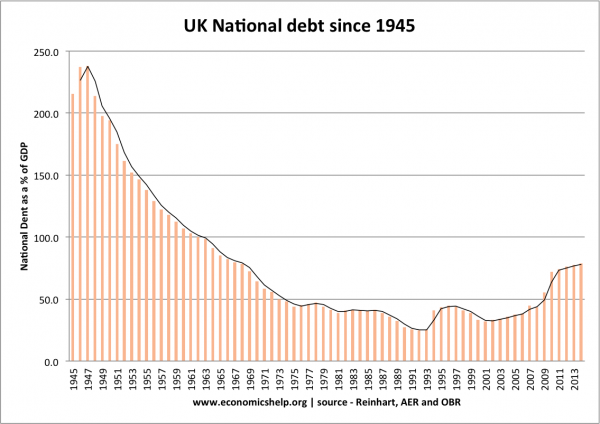

You’ve heard plenty of warnings about debt and deficits. But they never seem to play out like the crisis of the 70s, right? The question is why. Why does the British borrower, including the government, get away with debt and deficits that would make James Callaghan blush?

This morning I discovered a rather surprising chart to answer the question. It hammers home the importance of interest rates over debt and deficits. It explains why governments, companies and your neighbours have been able to live off debt, credit cards and refinanced mortgages. And it suggests the nature of the reckoning to come.

If I’m right about where interest rates are heading above, we are in deep trouble.

Having escaped the British schooling system shortly after Ms Francis taught me to read, my knowledge of Britain’s financial history is patchy. Especially given Irish and American schooling came next. Their versions of history are probably different to Ms Francis’.

So the following chart was a surprise. It shows you how horrific the budget crisis of 1974 really was. Remember, this triggered the British government borrowing money from the International Monetary Fund to stabilise the pound like some sort of third world country.

But it barely measures as a blip when it comes to Britain’s debt to GDP:

Sir John Major’s shambles in the 90s looks horrific by comparison, let alone the financial crisis budget. But neither have led to a crisis.

The debt and deficit wasn’t the problem in the 70s. So what made the budget crisis such a debacle?

Interest rates.

Interest rates on government debt were about four times higher.

Think about it like this. When you get a mortgage, what really matters most? The amount you borrow or the interest rate?

It’s the interest rate that determines how much you can borrow. It sets the repayment schedule too. And rates rising is what sends you broke.

Some of you know what happens when interest rates surge. You were busy dealing with your own surging mortgage interest bill back when Her Majesty’s government was struggling in the 70s too.

Well, if interest rates rise, we’ll feel that same effect. Only far more so. Total debt in the UK is vastly higher than in the 70s. Private debt is three times higher as a per cent of GDP. Government debt 50% higher as a per cent of GDP.

In a world of rising interest rates, all this finally will become the problem you’ve been hearing about for years.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: Central Banks