The relief rally in UK stocks is over. Now, cracks are beginning to emerge in the actual banking and financial system. The stresses of Brexit are showing up on balance sheets and in monetary policy.

The global debt bubble was a bug in search of a windscreen. Brexit is the windscreen. But the delayed reaction of financial markets is exactly what I mentioned in the Sunday video I recorded: you don’t find out who is affected most until a fund is frozen or someone has to sell another position to pay for losses (or meet redemptions).

I’ll get to all that in a moment. First, the Bank of England is back in the news and ratcheting up the recession risk posed by Brexit. ‘There is evidence that some risks have begun to crystallise. The current outlook for UK financial stability is challenging,’ wrote the Bank in its latest Financial Stability Report.

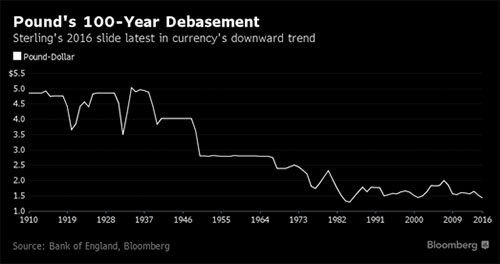

The Bank wasn’t talking about the fall in the British pound. But you should put the pound’s decline to fresh 31-year lows in perspective. The pound’s been falling since the late 1930s against the US dollar. Currency regimes come and go. Brexit itself is an attempt to revive Britain’s economic fortunes through new trade.

But the Bank is more worried about short-term liquidity in the financial sector. Its Financial Policy Committee took steps to free up bank capital for lending. It did so by reducing what’s called the counter-cyclical capital buffer (CCB) to zero per cent. It said it would hold it there until June 2017. It reckons that could free up nearly £150 billion for lending.

This is a weird one which you can easily misunderstand. But let’s have a crack. The CCB was put in place as a kind of hand-brake on bank lending in a boom. By requiring banks to beef up capital, it was supposed to mute the manic pace of lending in a credit boom.

Why?

Because booms always go bust. And when a credit boom goes bust, a bank’s losses on certain bad investments can wipe out its capital. That’s why there were bailouts in the last crisis. Bank capital wasn’t adequate to withstand losses and write-downs.

Under new EU laws that came into effect in January, government bailouts of banks are not allowed. Bail-ins are the new law of the EU land, in which bank creditors must pay to recapitalise the bank, not the public. This is currently being put to the test in Italy, which I’ll write about tomorrow.

For now, relaxing the CCB may free up liquidity. But it tells you something about the current situation when a measure designed to prevent a credit excess is relaxed… to prevent a credit bust. Double plus ungood.

The FPC said it stood ‘ready to take actions that will ensure capital and liquidity buffers can be drawn on as needed, to support the supply of credit and in support of market functioning.’ Meanwhile, the Monetary Policy Committee will chime in next Thursday when it meets to announce any changes to the UK bank rate (currently at 0.5%) or changes to the size or composition of the asset purchase programme. Stay tuned.

Swiss 50-year yields go negative

I’m nearly left speechless by the news that 50-year Swiss bonds traded with a negative yield earlier today. Nearly speechless. This is an e-letter, after all. And it’s my job to tell you why it matters and what it might mean.

What it means to me is that the world’s capital is being crowded into blue-chip stocks and negative yielding government bonds. It is perfectly rational madness, like chewing off your hand to escape being chained to a sinking ship. But in this case, you’re actually handcuffing yourself to the only part of the ship that hasn’t sunk (or has sunk the least).

The story I published last week showed why investors take on so much risk when they buy long-dated negative yielding bonds. Those investors can experience sudden and massive losses to their capital when interest rates rise. Rather than getting to safety, they’re getting a boat load of risk. You can read that article here (How central bankers robbed the world).

But you needn’t wait for a theoretical rise in interest rates to see how much damage low and negative rates are already causing. Insurance companies, pension funds, and income investors must take on greater risk to find higher-yielding securities as government bond yields go lower. For example, it appears Japanese money is pouring into the US Treasury bond market, driving 10-year US Treasury yields to 1.38%. What next?

Property aftershocks

The long-term consequences of lower (or even negative) US Treasury yields is beyond the scope of today’s letter. Suffice it to say: probably good for gold. But let’s finish today by talking about UK property funds.

Standard Life, purveyor of a £2.9 billion property fund, has suspended redemptions from the fund for 28 days. It will review the suspension every 28 days. The fund says the suspension will relieve it from having to liquidate property quickly to cover redemptions.

There’s lots to say about this. My colleague John Stepek wrote about it in detail in Money Morning today. The main point for me is that this is directly related to the concern that Britain post-Brexit will have trouble funding its current account deficit. If capital ceases to flow to London, you can understand why investors would want to liquidate an investment—London property—that depends on capital flows.

It’s not at all clear to me that a lower pound makes London property less attractive to foreign investors. But the situation is fluid at the moment. And capital markets don’t know what to make of it. Investors, choosing discretion as the better part of valour, have voted with their feet—until Standard Life blocked the door.

It’s not a Lehman moment. But it feels a bit like a Bear Stearns moment. A moment when a nominally small matter at the periphery of the financial system triggered a series of reactions that became a wider crisis. Let’s hope it’s not that again.

But let’s plan like it is.

Category: Central Banks