Another red day in the markets. Even if China isn’t the next Lehman, there is still the little problem of where growth is going to come from. That’s one reason 29 of the 30 Dow components fell in Wednesday’s trading. I’ll get back to the bad breadth in the market in a moment.

Spare a thought for the nine members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. Those luckless souls have the fate of British interest rates in their hands again today. If the past 82 months are any indication, though, they’re not going to do anything. Britain’s benchmark interest rate has stayed 0.5% for nearly seven years now.

Sterling should continue its downward trend against the US dollar if the Bank does nothing. Yesterday’s November industrial production (-0.7%) and manufacturing figures (-0.4%) from the Office for National Statistics don’t argue for higher rates. And neither does the oil price!

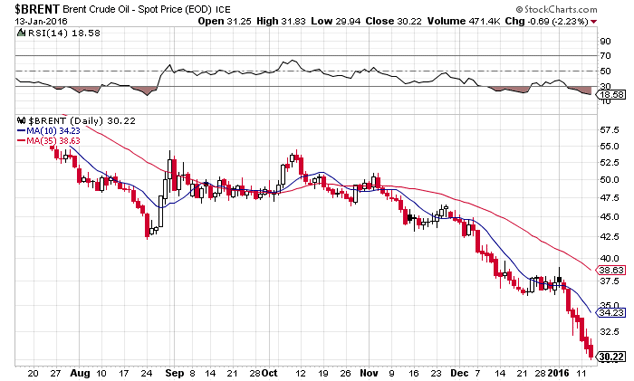

How can the BoE raise rates when oil is at a 12-year low?

The low oil price is a “risk” to the bank’s 2% inflation target, according to wire service reports. See how that works? You can’t raise rates to slow down the economy if the economy hasn’t speeded up, which you measure by inflation that doesn’t exist (yet).

By the way, the oil chart above shows an inflation trap the Bank would surely be aware of. If and when the oil price spikes again – and that is almost a certainty at some point – how far behind will inflation be? That’s the trouble with inflation targets. You never get just 2%. You never get a little inflation. You get a lot of it. And all at once.

The best reason for the bank not to raise rates is that British households have a lot of debt. According to the Bank’s own figures, the household-debt-to-income ratio is 135%. It was higher in 2008, at 168.7%. But the average Briton has £11,800 in unsecured (and interest-rate sensitive) credit-card debt. Between mortgages and credit-card debt, a rate rise would bite.

All the interesting things in economics happen at the margin

Most Britons with a mortgage could probably handle a rise in rates. And not everyone has a variable rate mortgage to begin with. But new buyers? Hmm.

Finally, a weaker pound is just what the manufacturing industry needs, at least in theory. If Britain wants to shrink the current account deficit, it needs to import less and export more. The BoE can help that by leaving rates unchanged. It’s not hard to do. All you have to do is nothing.

The Bank would do less damage to the economy by doing nothing. But if you’re going to do nothing, why bother to exist in the first place? Over the weekend I’m going to republish the argument for abolishing the Bank of England. It was made in a paper recently published by the Adam Smith Institute. Look for it on Saturday.

Category: Central Banks