It’s a sign of the times. Provident Financial and Royal Mail were kicked out of the FTSE 100 index yesterday.

The Royal Mail blamed its slump on Brexit. A lack of confidence is reducing direct mail advertising. Nothing to do with the internet.

Provident is far more interesting. It has supplied credit to iffy borrowers since 1880. After banks exited the business in the wake of 2008, Provident filled the gap and profited handsomely. Shareholders did too. Until this year.

While mortgage lending hit a post-2008 high of £21.2 billion in the UK, Provident’s home credit business is set to publish its first annual loss. Collections went from 90% last year to 57% this year.

Yikes.

Sales are £9 million less a week than last year too. The share price crashed 65% in just one day.

Having a major sub-prime lender implode doesn’t exactly fit the narrative of a steady economy with inflation, unemployment and lending all proceeding nicely.

What’s going on?

The answer might be in the new phenomenon of poor wage growth. Around the world, pay hasn’t kept pace with inflation, GDP or profits. The share of profits going to workers is falling.

According to the International Labour Organisation, without China things are particularly dire:

Wage growth around the world has decelerated since 2012, falling from 2.5 per cent to 1.7 per cent in 2015, its lowest level in four years. If China, where wage growth was faster than elsewhere, is not included, growth in global wages dropped from 1.6 per cent to 0.9 per cent, according to the ILO’s Global Wage Report 2016/17.

The question is why. There’s been plenty of debate on this among economists.

Some of the answer is that we’re still absorbing the unemployed of the 2008 mess. With unemployed around, business doesn’t need to raise wages to attract workers. That’s a supply-based argument.

According to the business world, the lack of demand for employees is because of regulation and uncertainty over things like Brexit. And they have quite a list of specifics to point to according to the Financial Times:

Two-thirds of the companies surveyed said they would have to “take action” in the next three years to cope with the national living wage, the new minimum wage rate for over-25s that is set to rise from £7.50 to £8.75 an hour by 2020. Almost 40 per cent of firms surveyed said they would raise prices, while 25 per cent planned to reduce pay growth for the rest of their workforce.

Three-quarters of companies said they had seen costs go up because of the requirement to enrol all staff in a workplace pension. A fifth of businesses had also been affected by the apprenticeship levy — a payroll tax of 0.5 per cent on all employers with salary costs of £3m or more, which started this April.

If you think it through, firms hire employees until the extra employee doesn’t provide a benefit greater than their cost. Raise the cost of hiring and you tip this balance to a lower level of hiring at a lower wage. Or business must cut the cost elsewhere. Hence the 25% of business reducing pay growth.

With policies like this, we might as well be in the EU.

Poor Daniel Hannan, MEP. He fought so hard for Brexit so we wouldn’t be beholden to poor economic policy. Meanwhile his national government has been busy doing just that anyway.

At least that’s what I expect he’s thinking. He’ll tell you himself if you can make it to our 6 October conference. The theme is free markets vs central planning. That couldn’t suit Hannan any better.

The rest of the world is debating about the nature of the central planning. Governments or central bankers? Left or right? Globalism or nationalism?

Meanwhile the biggest boom in investment markets is the one government has least control over. Bitcoin is reaching all-time highs. Doesn’t that tell you the solution to things?

If the world has framed the debate wrong in the first place, things could change very quickly. How much of a shock was Brexit? Where is the next shock coming from?

You need the guidance of people like Hannan to predict how the next change will come about. Join us in October for his insight.

The cost of borrowing continues to fall

Back to debt. How can a mortgage boom be on that leaves behind less creditworthy borrowers and while wage growth is poor?

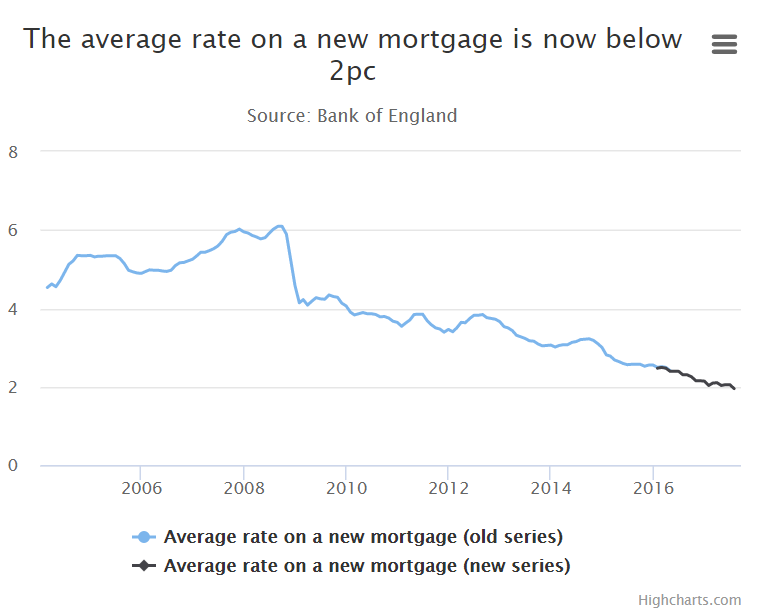

The answer, as always, is central banks. Thanks to their policy, mortgage rates are at the lowest level on record in the UK:

It’s fascinating to see how the costs have dropped steadily since 2009. We have inflation above the Bank of England target, low unemployment and some GDP growth, but borrowing costs continue to fall.

The steady reduction since the financial crisis can’t be due to monetary policy entirely. Banks are increasingly accepting the low interest rate environment as a long-term phenomenon. They’re willing to bet rates won’t rise soon.

But our publisher Nick O’Connor isn’t accepting lower prices. He’s planning to hike the price of his best performing investment advisory. A threefold increase!

Find out why, and how you can get in now before the change here. You have hours, not days.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Category: Brexit