Editor’s note: With the Nasdaq and S&P 500 hitting new highs this week, optimism is abounding in markets. But as you’ll see below, optimism has a danger to it where markets are concerned. With analysts forecasting the fastest economic growth for the UK since World War II, we want to encourage readers today to take a step back and consider the long view. With that in mind, I’m sharing this article that appeared originally in Southbank Investment Daily in April. Enjoy – Boaz Shoshan

The tech leaders assembled were bent on changing the world – and had already made fortunes doing it.

And in a year where tech stocks were surging as much as 27-fold, many were sitting on investments with sky-high valuations – which they felt just fine about, thank you.

Besides, why should they take any lectures from the man who had missed the extraordinary tech boom, and whose own firm was on track to finish the year down 22%?

There were polite nods as Warren Buffett took his place behind the lectern. In his 58-year career, he had never made a public market prediction – not in his rare speeches, nor in his fabled annual meetings with Berkshire shareholders.

But today he was breaking that rule.

400% growth amid a 17-year bear market

Buffett didn’t have a warning for any market movement to take place next week, next month, or even next year.

“Though I will be talking about the level of the market, I will not be talking about or predicting their course of action over the next year,” he told them.

“Valuing the market has nothing to do with where it’s going to go next week or next month or next year, a line of thought we never get into. The fact is that markets behave in ways, sometimes for a very long stretch, that are not linked to value.”

Even so, Buffett warned those assembled that they were expecting too much in the long term.

He clicked over to a PowerPoint slide of the last 34 years of the market, beginning with the years 1964-1981.

DOW JONES INDUSTRIAL AVERAGE

December 31, 1964: 874.12

December 31, 1981: 875.00

In 1964, Buffett pointed out, few would have suspected the bear market that was to follow.

During these 17 years, the size of the economy grew five-fold. The sales of the Fortune 500 companies grew more than five-fold. Yet during these 17 years, the stock market went exactly nowhere.

Buffett acknowledged the white-hot performance of the market in recent years, and outlined some ways it could be expected to continue. Interest rates could fall (remember, this was the 1990s). Or investors could carve out an even greater slice of the economy for themselves, as opposed to workers and government, than the historic levels they had already secured.

Or, the economy’s growth rate could accelerate. Buffett called all of these scenarios “wishful thinking”.

Valuations didn’t determine the market’s course over the short term. But over the long term, he warned, reality would catch up to lofty valuations.

Of course, this was just the broader stock market. What about the few spectacular companies, owned and often founded by his audience members?

Lessons from the last tech revolutions

Buffett pointed to the last two great tech innovations of the 20th century – the automobile and the aeroplane.

He pulled up a chart that contained just half a page of a 70-page list of all the auto companies that had ever existed in the United States.

There were two thousand auto companies: the most important invention, probably, in the first half of the 20th century. If you had seen at the time of the first cars how this country would develop in connection with autos, you would have said: “this is the place I must be.”

But out of those thousands of car companies, Buffett pointed out, only three had survived.

As for aeroplanes? The industry had launched 300 companies from 1919 to 1939. But as of 1998, Buffett revealed, an aggregate of 0% had been made from all the returns in the history of the aviation sector.

The explicit message was that historic revolutions don’t really mint millionaires at the rate most investors imagine.

The implicit message was that the internet would be no different in the long run – a point that especially rankled the Masters of the Universe in the audience.

Was Buffett right?

In the sense that Buffett made a very general warning rather than a specific prediction, he was absolutely correct. A day of reckoning was in store for the tech companies floating at nosebleed valuations. In fact, it was just months away.

Buffett’s friend Bill Gates was in the audience that day. In less than a year, the share price of his Microsoft would plunge 37%. Buffett’s example of a 17-year bear market would prove especially poignant for Gates: it would take 17 years, or until 2016, for Microsoft shares to reach their 1999 levels.

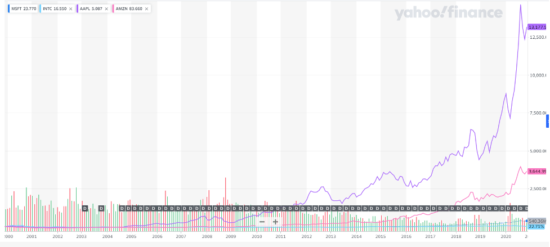

Andy Grove, co-founder of Intel, was also in the crowd. He would see his company do even worse. As you can see, Intel returned -8% over the next 17 years, compared to Microsoft’s 22% return and the S&P 500’s 48%.

Source: Yahoo Finance

Source: Yahoo Finance

But while the correction was coming, it turns out that past wasn’t quite prologue for the third tech revolution of the 20th century: the rise of the internet and home computers.

According to some analysts back in 2017, Microsoft created as many as 12,000 millionaires, in addition to three billionaires by 2005. Google’s initial public offering (IPO) created over 1,000 millionaires by 2007 – and the stock would rise more than 700% in the following years.

And despite the correction of the dotcom collapse, investors who held on to Amazon and Apple for the wild ride would be glad they did. Those stocks returned 3,000% and 13,000% respectively since Buffett’s 22 November 1999 warning, as you see here:

Source: Yahoo Finance

Source: Yahoo Finance

Notably, even Warren Buffett – the value investor who only bought what he could understand and shunned tech stocks – would eventually get into Apple. As of March this year, he was up nearly $100 billion on his position.

Now, Buffett’s 1999 warning about overvalued markets could easily apply to today (in fact, the Nasdaq and S&P 500 hit new record highs this week).

I believe the next market meltdown could be triggered by another Black Swan event (my colleague Nickolai Hubble explains how the death of the euro could affect markets in this interview here).

But whether the bust is set off by overvaluations or the EU, Buffett’s warning – and the extent to which it held up in the years after the internet boom – is relevant to any investor trying to make sense of these changes.

It’s also crucial for understanding the danger of today’s markets. Staying in can be devastating if we’re on the eve of another long bear market. But exiting prematurely could leave profit potential on the table.

Last week I spoke to a CEO whose company is addressing this basic conundrum for investors – when to get out, and when to get in.

Thanks to the investing tool he helped develop, he knew when to get out of markets – he was 97% cash – on 27 February 2020.

When he shared his warning on stage, some attendees at the Florida conference scoffed. But when the global selloff began days later, this CEO was vindicated – not to mention when his tool alerted him to US markets’ recovery in late March 2020, as well.

Next week, we’ve arranged for him to appear in a special event, The Final Rally, to brief readers on the condition of markets today and pass on an urgent message. If you haven’t already, I urge you to secure your free spot in seconds here.

Regards,

William Dahl

Editor, Southbank Investment Daily

Category: Economics