Our government’s dire financial position is in the news. Again. As usual.

Even a pandemic hasn’t changed the story much. What meaning does adding another 0 really have to every media story on the topic? Do you really understand just how much more dangerous 100 billion is relative to 10 billion?

The first financial book I ever read was about the US government’s debt. And, many years later, with a zero added there too, there still hasn’t been a fiscal reckoning. Any sort of reckoning, really. Heck, interest rates on US government bonds are lower now.

Even the Tea Party movement couldn’t stop the US government’s deficits. Democracy and deficits just aren’t separable.

Even if UK austerity and the Tea Party had delivered, coronavirus has blown the deficits of all governments out of the water. And the accountants who work for the government are as worried as ever. Or more worried – I can’t tell there either.

A Financial Times article begins like this: “Tax increases of £60bn or a return to austerity will be needed to restore the UK’s public finances to stability after coronavirus, the fiscal watchdog said on Tuesday.” “Britain nearly went bust in March, says Bank of England” was a Guardian headline. Not that the Guardian is doing much better according to its layoff notices.

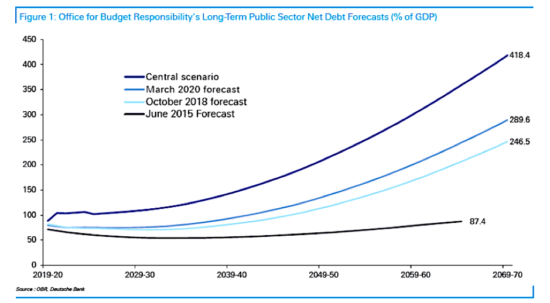

The real shocker was this chart from Deutsche Bank using the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts. From an 87% debt to GDP forecast in 2015 to a 418% debt to GDP by 2070…

Source: Holger Zschaepitz, Twitter

Source: Holger Zschaepitz, Twitter

World War II debts brought our debt to GDP to about 270%. So 418% is quite an achievement. If we ever manage to pull it off…

But today we look at the solutions for this lost cause. Not for the Guardian, for the government’s debt.

And I use that word “solutions” very loosely. Because what’s a solution for our Chancellor of the Exchequer is very unlikely to be a solution for you…

Option 1 for dealing with deficits is of course tax hikes. Those may or may not be in the works according to several media reports.

Option 2 is of course tax cuts.

Yes, I know, welcome to the wonderful world of economics, where you can have it both ways, or neither, depending on which economist you’re talking to about which particular topic. They’re worse than epidemiologists.

The idea of tax cuts solving the problem of too much debt is that the economy grows faster, thereby growing the GDP and even tax revenue, eventually.

Now economists and media pundits love to debate this point. Do tax increases raise or lower revenue? And the same for tax cuts.

The idea is usually shown as a chart with something called the Laffer Curve on it. It’s more of a hill – the sort the Grand Old Duke of York spends his time on, going back and forth, discovering neither option works as well as theory suggested.

Why the hill shape for the Laffer Curve? According to President Reagan’s adviser Art Laffer, at low rates of tax, a tax hike probably raises revenue. But at high rates of tax, a tax cut has such a good effect on the economy that it also raises revenue. Perhaps by bringing black market economic activity back into the fold, for example.

The point of the Laffer Curve is to illustrate that there is an optimal level of tax rates, to collect the maximum amount of tax revenue. Because that is of course a good thing…

My own views on the matter are best displayed by how every computer game handles this trade off. Because computer game engineers keep the blatantly obvious simple.

Higher taxes raise more revenue in the short run, but at the expense of economic growth. Eventually, that lack of economic growth leaves you with less tax revenue than you would’ve had by keeping tax rates low.

The result is a strategic trade-off, in the game. Where time is the key consideration. Something the Laffer Curve ignores.

If you can make your computer game civilisation function with low taxes, your economy will outgrow your competitor’s over time. And you will win. But there is a risk…

In games, this trade-off is of course all about how much you can spend on raising an army to slay your opponents. Tax too low and you get wiped out by other players’ higher military spending early in the game. Tax too high and your economy will be stunted as the game goes on. When your enemies turn up with superior expensive tech, you get wiped out too.

Back in reality, it’s all about political parties being able to bribe the swing voters instead of slaying the other player. But it’s all a game there too.

The Office for Budget Responsibility is signalling that our current settings are disastrous. But I’m not sure fiddling with taxes will help.

Option 3 for dealing with the deficit was the topic of our recent monthly issue at The Fleet Street Letter Monthly Alert. Check out Friday’s Capital & Conflict for more on the topic. And buy gold.

Today, we explore option 4. Something that hasn’t been done for hundreds of years. And it reads more like a science fiction novel than a fiscal strategy…

But there is a precedent.

Back when the French king was a few years old, the Duke of Orleans was the Regent and a Scotsman named Law ran the French public finances (into the ground), a similar scheme was attempted.

Back then, France was in fiscal trouble too. They tried a bit of option 2 above first. But the tax cut caused political trouble in ways Art Laffer had failed to predict hundreds of years later.

And so John Law came up with a solution. France had acquired the Mississippi Valley in the US. By which I mean that the French government owned the place. And nobody was allowed to trade with it, unless by Royal Assent. Which could be bought.

And that sort of agreement is actually what created the weird and wonderful world of joint stock companies like the ones you own in your pension fund today. Investors got together, formed a company and bought trading rights off the government. Hence the names East India Trading Company and Mississippi Company.

Law’s idea was to sell the trading and mineral rights of Louisiana to such a company. In exchange for that company buying the French national debt. A type of debt for equity swap, if that doesn’t confuse you. The company gets the benefit of being allowed to trade with Louisiana and the French government gets fiscal stability.

To make the scheme work, there had to be a speculative mania which would make Elon Musk blush. There had to be such a clamouring for Mississippi Company shares that it would make the French government debt disappear into the Mississippi Company’s coffers.

And that worked surprisingly well. In ever increasingly creative ways. Until the bubble burst and the Mississippi Bubble managed to ruin both the public and private financial affairs of France – a decent achievement for a bubble.

How is this relevant to today?

Well, I was reading the biography of the man who managed to become a Mississippian, meaning millionaire from speculating in Mississippi stocks, and escape with his fortune too. He did it again with another bubble in the UK shortly after, while also founding the science of economics, if it is a science, on the side. But that’s another story.

I was thinking about how it’s a shame we don’t have a new North America to discover. We could send the Royal Navy off to colonise it and then sell it off like John Law did, thereby solving the problem of the national debt.

And then it hit me. The world does have such a place. A source of vast future wealth which governments have effective ownership of, or at least control of, but to which they could sell the economic rights today. And the technology we need to begin reaping the economic rewards of such a place is approaching realisation.

Anyone know where I’m talking about?

nickolai@southbankresearch.com

Nick Hubble

Editor, Southbank Investment Research

Category: Market updates