Most of those in political office, quite understandably, are firmly against inflation and firmly in favor of policies producing it. (This schizophrenia hasn’t caused them to lose touch with reality, however; Congressmen have made sure that their pensions – unlike practically all granted in the private sector – are indexed to cost-of-living changes after retirement.)

Warren Buffett penned that for Fortune magazine back in 1977. The more things change, the more they stay the same…

Charlie Morris forwarded me that article as an aperitif for what he’s writing for The Fleet Street Letter Monthly Alert subscribers. Buffett’s writing can be quite dense, but the gems that can be extracted are shiny indeed.

He continues, emphasis mine:

Discussions regarding future inflation rates usually probe the subtleties of monetary and fiscal policies. These are important variables in determining the outcome of any specific inflationary equation. But, at the source, peacetime inflation is a political problem, not an economic problem. Human behavior, not monetary behavior, is the key. And when very human politicians choose between the next election and the next generation, it’s clear what usually happens.

“Very human” is probably too complimentary a description of the modern political class here in 2020, but they’re certainly doing their bit to create inflation. Good luck to any aspiring politico with an agenda to limit or – heaven forbid – reduce government spending.

To spend taxpayers’ money is to be a righteous man these days. “Fiscal stimulus” is the name of the game. As we wrote yesterday, the UK government’s debt pile is now greater in size than the entire UK economy – and they sure as hell ain’t stopping soon.

The most tragic aspect of inflation is that while the government spending which creates it is often sold to the public on the basis of helping the poor, it is the poorest in society who suffer the most from it. It is the poor who have the greatest proportion of their wealth in cash – they aren’t loaded up with gold or real estate that might protect their savings. And in the case of more aggressive inflation, they don’t have the cash to go buy food and necessities in bulk at wholesale prices from places like Costco either.

But sadly, it’s almost impossible to imagine somebody like Reagan running around Whitehall, describing inflation as “violent as a mugger, as frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hit man.” For that to happen today, inflation would need to make a major comeback – the thesis we’re exploring in the upcoming issue of The Fleet Street Letter Monthly Alert.

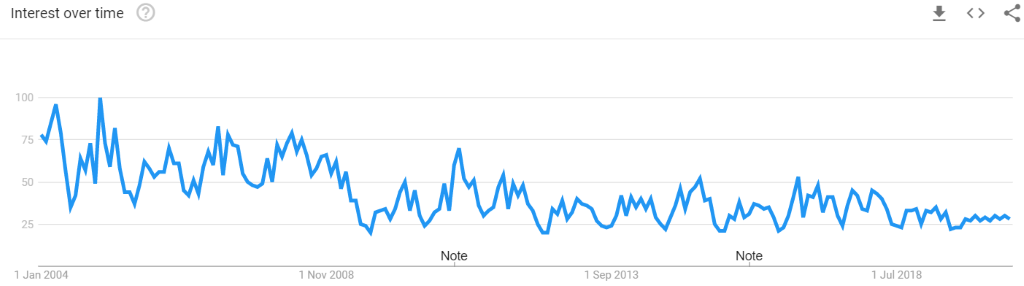

Inflation in the real economy has been low enough in recent history for nobody to notice it gradually eating away at their wealth. Indeed, Google search popularity for inflation in the UK in the “news” category has gone from unpopular to completely flatlining last year:

Inflation is on nobody’s radar right now, which is a reason by itself to give it another look. But more compelling is the case of central banks printing money and governments spending it at the same time and with increasing volume.

The return of inflation in a big way is a scenario that investors are ill prepared for. While you might think that stocks, being claims on businesses with real assets, might retain their intrinsic value in the face of a currency losing its value (ie, rising in price as the currency falls), in reality this is a flawed assumption which could get you and your portfolio in a lot of trouble.

Especially if you’re looking at the stocks which have performed the best in recent (low inflation) years to hold their value in the face of higher inflation. Inflation can be a killer to the price of some stocks, and the solvency of some companies.

Probably the most extreme and vivid example of how inflation can brutalise investors would be the case of Weimar Germany. Liaquat Ahamed illustrated the situation in great detail in his book, Lords of Finance:

During the hyperinflation, few people had believed that capitalism would even survive in Germany and equities had become dirt cheap, having fallen to less than 15 percent of their 1913 inflation-adjusted value—the whole of the Daimler-Benz motor company, for example, could have been bought for the price of 227 of its cars.

The entire company of Mercedes was worth 227 of its cars – a steal, if you could weather the awful storm which was to come. Mercedes is worth roughly 372,000 of its G-Wagons today…

But as I say, that’s a much more extreme example – we’re not predicting hyperinflation here in the UK. But it wouldn’t take hyperinflation to give the likes of growth companies a big knock. Low inflation has kept borrowing costs low too, which has been great for companies which borrow vast quantities of money to keep ticking over while they try to conquer the world with a new service or product.

Inflation puts a gigantic spanner in the works of this dynamic as banks and investors begin raising their lending costs to keep on top of the falling value of money, choking companies which rely on borrowing to stay afloat.

It is possible for stocks to be a hedge against inflation – but they need to be the right stocks, bought at the right price. It may sound strange, but stocks that are priced very highly today will not necessarily become more expensive if the currency it is priced in is worth less.

Or as Charlie put it to me over the phone the other day in his standard jolly tone, and as though this was all actually very obvious, “If gold was a million dollars an ounce, it wouldn’t be a very good inflation hedge.”

More to come,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

PS Buffett’s article does show its age a little with comments in passages like this:

Stocks are quite properly thought of as riskier than bonds. While that equity coupon is more or less fixed over periods of time, it does fluctuate somewhat from year to year. Investors’ attitudes about the future can be affected substantially, although frequently erroneously, by those yearly changes. Stocks are also riskier because they come equipped with infinite maturities. (Even your friendly broker wouldn’t have the nerve to peddle a 100-year bond, if he had any available, as “safe.”)

Fast forward 43 years and over a dozen countries, let alone companies, have been issuing century bonds (borrowing money for a hundred years), with investors buying them up as “safe”. Not if inflations returns they ain’t…

For charts and other financial/geopolitical content, follow me on Twitter: @FederalExcess.

Category: Market updates