JMW Turner, one of the greatest artists born in Britain, was a notoriously reclusive man. But it’s one of his finest works which has recently “gone into hiding”.

The Fighting Temeraire, tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838 was voted Britain’s favourite painting back in 2005. It depicts a grand ship of the line, a man-of-war from the age of fighting sail, being dragged to its destruction by a steamboat – the very technology that has made it obsolete. The sun is setting as the ship, which in real life fought at Trafalgar, is being hauled away into history.

It’s a beautiful painting, which has recently gone missing. Not from the National Gallery, where it still hangs… but from our everyday transactions, where the great painting was supposed to make regular appearances. The Bank of England first announced to great fanfare that The Fighting Temeraire and Turner’s self-portrait would grace the new polymer 20-pound note back in 2016. The notes were finally beginning to be injected into our currency supply on 20 February this year – just as the WuFlu panic was stirring and the very curious fear of money itself arrived, as banknotes and coins were shunned like rats carrying the plague.

I still haven’t even seen one of the new twenties. People don’t wanna pay with it, stores don’t wanna take it… and organisations like the World Health Organisation and the European Commission are encouraging both.

It’s an interesting new twist on the War on Cash. Another step closer to a cashless society, where negative interest rates can be charged on any deposit… where all transactions can be surveilled and analysed by the state… and where politicos can instantly credit the accounts of whichever segment of the population they’re trying to get votes from. Just like the Temeraire being dragged away, pound notes are being dragged into the history books too… though there is a major stumbling block in the way of this dystopian future as we’ll come to.

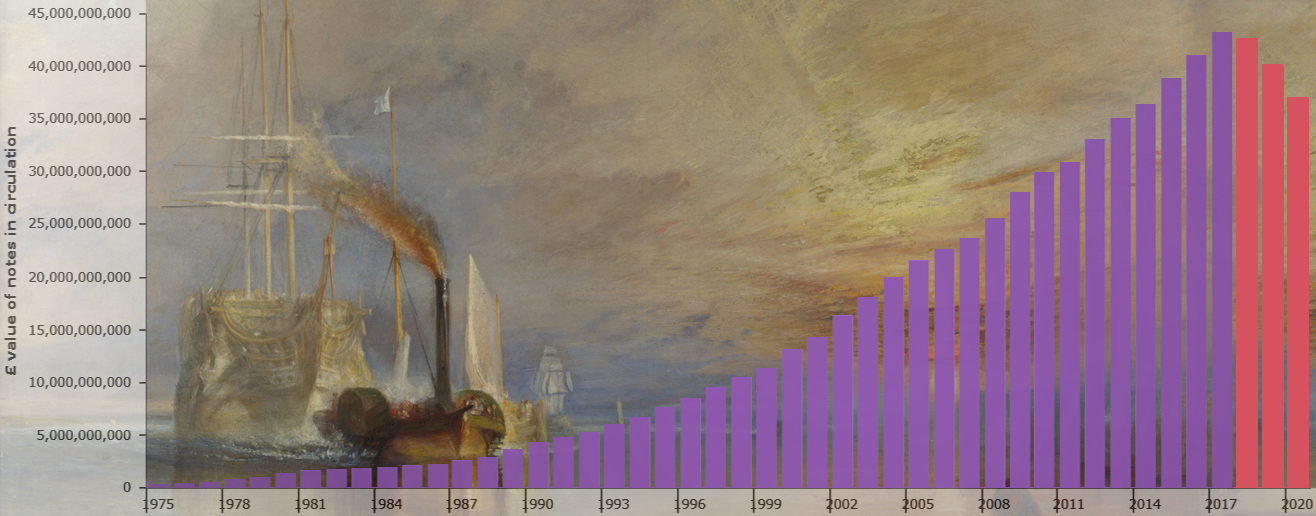

But like many consequences of the WuFlu crisis, it has merely accelerated an existing trend rather than created a new one. There’s been a bear market in 20-pound notes for three years, with the peak at the beginning of 2017 breaking a multi-decade trend:

The bear market in 20-pound notes, click to enlarge. Data sourced from the Bank of England

The bear market in 20-pound notes, click to enlarge. Data sourced from the Bank of England

By the time The Fighting Temeraire arrived, the tide for twenties was already going out. Twenties are key, as they’re by far the most popular pound note in both value and absolute number of notes in circulation. The lack of demand for physical cash is also illustrated by the decline in ATMs, with the number of free-to-use ATMs declining by 13% last year.

What happened in 2017? Well, that was the year of the crypto boom. But it may simply have been the relentless rise of digital payments, both through online stores and through mobile payment systems (like Apple Pay), which have put a dent in the demand for twenties.

Interestingly, the demand for 50-pound notes remains on the increase, having only fallen between 1993 and 1994, and 2011 and 2012. There’s 17.5 billion quids’ worth of the big red ones out there, which you could attribute to several factors – the increase in inflation giving them more utility, banknote hoarding due to a fear of negative interest rates (as is currently occurring in Europe) or maybe the growing divide between the have nots and the have yachts.

But the rise in demand for the fifty (surpassed in splendour by Scottish £100 notes of course) is a sideshow to the rise of digital currency – the steamboat hauling physical cash into the history books. While this is occurring, we’ve seen another big spike in bitcoin, in an almost symmetrical move. There’s a big event coming up for BTC in a week’s time, as we’ll explore in tomorrow’s letter, but for today I suggest you take a look at what Gary Cohn wrote in the Financial Times a few days ago.

Cohn worked at Goldman Sachs for 25 years, becoming a senior executive before joining the Donald Trump administration as chief economic adviser. He resigned when he realised that Trump was serious about ending globalisation as we know it, and from there took his career in a different direction – getting into what is effectively the crypto space, though he wouldn’t call it that (think “fintech” and “digital wallets”).

Cohn’s piece is illustrative of what financial authority figures expect to see in the future – his article, titled “Coronavirus is speeding up the disappearance of cash” is what you’d call a trial balloon of ideas we may see proposed and implemented in the future if they catch on. From the FT:

Are we about to abandon a practice that dates back some 7,000 years to Mesopotamia? Over the centuries, physical money has evolved from tokens that represented goods in warehouses, then precious metals, and now our system uses coins and paper and plastic notes based on faith of the central banks.

The coronavirus pandemic, and our efforts to cut disease transmission, is forcing us to ask whether we have outgrown the need to carry and move money in physical form. We already have the technology to pay and transact in a purely digital fashion and use highly secure biometric authentication at the point of transaction. If we shifted to digital, no one would carry dirty cash or coins or deal with a cheque again.

It is eminently possible: 87 per cent of transactions in Sweden occur digitally through private payment companies. They tend to commingle clients’ money in a few bank accounts, giving individuals access to funds through apps. If central banks around the world created digital currencies, each person could have a segregated account. This idea is gathering steam. US Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown initially sought to include digital banking as part of the coronavirus response. He wants the US Federal Reserve to create digital dollar accounts and wallets for all citizens…

Digitising payments would also make it much simpler for individuals to calculate and file their income taxes and for governments to make sure they are being paid. There are privacy implications to the government having access to individual and corporate wallets that would have to be considered, but think about how much quicker and efficient the tax process could be…

Either way, the slow rise of digital currency has been given a gigantic boost by the pandemic. The shift will be disruptive but is clearly a leap in the right direction.

Articles like this are worth paying attention to whether you like the idea of such a future or not, as these individuals have great influence on the direction of where our financial system may end up going.

I’m no fan of cashless societies and the great authoritarian trap such a system leads to. However, I believe that ironically, what may save us from the creation of such an authoritarian system of control are the authoritarian urges of governments themselves. In a cashless society, how does a government finance clandestine operations, like espionage?

One of the main objectives of these digital payment systems is to add greater transparency, and letting a bank and all merchants you interact with see that your funding comes from MI6 is not gonna help all the James Bonds out there keep a low profile. At the very least in a cashless society, a bank would need to process the spending activities of the operators in question, would know the funding was coming from the government, and would see what it was buying from whom, and where. I’m no expert when it comes to intelligence, but cutting a bank into the operations you want to keep secret doesn’t sound like good operational security to me…

On a separate note before I leave you for today, a reader wrote in a while back with an interesting observation on the “banknote plague”:

Imagine we still used gold and silver as money instead of those plasticky, animal fat-infused notes. Silver in particular is well known for its antiviral effects… so not just better for our economic health, better for our literal physical health too. It feels like there’s some irony in this somewhere. I wonder how much the virus is currently spreading in parts of the world where fiat is still more widely used than contactless payments…

Way out in Utah, an organisation called the United Precious Metals Association (UPMA) has made banknotes out of wafer-thin gold, which it calls “goldbacks”. Due to a loophole in Utah law, these are actually legal tender and can be used for payments. UPMA recently stopped giving these away for free, though we were happy that many of our readers got in on the opportunity when we wrote about it late last year (How to get free gold – 4 October 2019). I wonder if it’s thought of its creation from an anti-viral perspective…

All the best,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Uncategorised