If you’ve been reading this letter for a while, you’ll likely know I often compare events occurring now to those that have occurred in the past. My Cold War II thesis is probably the biggest example of this, though in more recent letters and in a recent episode of The Daily Blitz I’ve noted the striking similarity this year has shared with 2016 – and whether 2020 will be a repeat of the ragingly bullish 2017.

Past performance is no indicator of future results of course, as the financial industry, ourselves here at Southbank Investment Research included, is compelled by regulation to remind you – but there is also nothing new under the sun. You’ll often find that history can repeat as human nature never changes and the plans that have failed in the past are put forward, afresh, once everybody that could remember the failure have forgotten, or died.

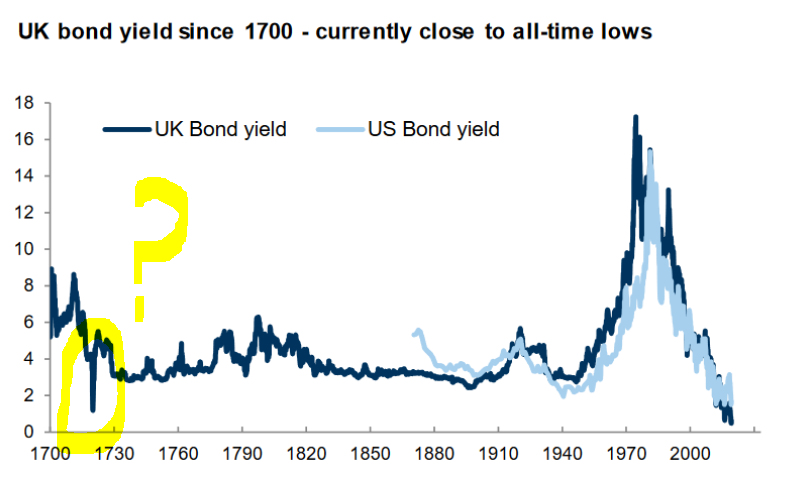

With that in mind, I was struck by a certain chart of UK interest rates, mapped out since 1700. Within it may be a clue to our future – and a radical, albeit destructive solution to the global debt problem.

What happened at the beginning of the 18th century that drove interest rates so low that they’re almost as low as they are now?

More specifically, how did the British government manage to ensure that it paid such low interest on its debts?

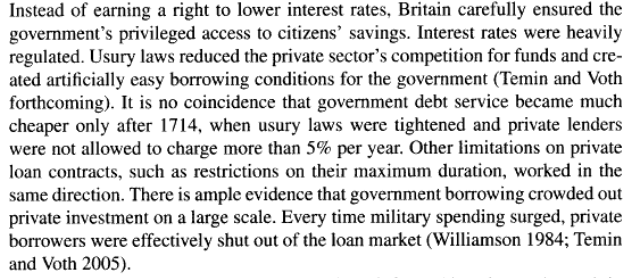

Well, one way of doing it was simply to regulate everybody out of the market when they needed cash:

Drelichman, Mauricio, and Hans-Joachim Voth. “Debt Sustainability in Historical Perspective: The Role of Fiscal Repression.” Journal of the European Economic Association 6, no. 2/3 (2008): 657-67. www.jstor.org/stable/40282674.

Drelichman, Mauricio, and Hans-Joachim Voth. “Debt Sustainability in Historical Perspective: The Role of Fiscal Repression.” Journal of the European Economic Association 6, no. 2/3 (2008): 657-67. www.jstor.org/stable/40282674.

It’s worth noting that following the financial crisis, governments around the world including here in Blighty have introduced significant regulation to ensure investment funds and banks own greater quantities of “safe assets” – which just so happens to be that very same government’s debt. Call me cynical, but I doubt keeping banks and investors safe was their only motivation.

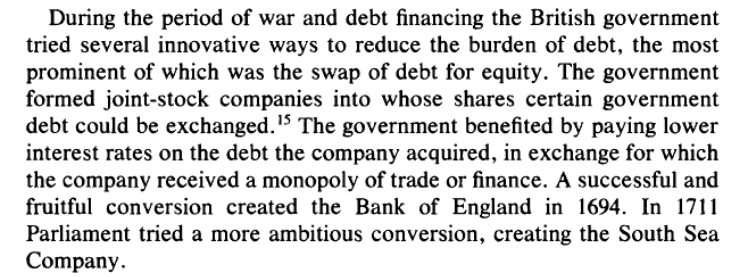

However, it’s also in the early 1700s that we come across an intriguing solution to the debt problem. A solution which has not been attempted in the modern age, but which myself and Nickolai Hubble can imagine being employed once more in the future – on an even greater scale.

You’ll likely already have heard of the South Sea and Mississippi companies, the stocks of which went down in history as being the biggest bubbles of all time, with a subsequent crash to match.

But one part of why these stocks gained so much investment capital is often overlooked:

Schubert, Eric S. “Innovations, Debts, and Bubbles: International Integration of Financial Markets in Western Europe, 1688-1720.” The Journal of Economic History 48, no. 2 (1988): 299-306. www.jstor.org/stable/2121172.

Schubert, Eric S. “Innovations, Debts, and Bubbles: International Integration of Financial Markets in Western Europe, 1688-1720.” The Journal of Economic History 48, no. 2 (1988): 299-306. www.jstor.org/stable/2121172.

One of the ways in which the British government managed to corral so many investors into buying their debt (in turn, reducing interest rates) was to write a speculative promise into their bonds. If you owned the debt, you could convert it into the stock of a newly formed company which had been granted a monopoly over trade (in this case, in the South Sea) by the government.

The conversion from debt into equity was done at a rate considered very profitable, to get people to buy the government bonds first rather than simply buying the stock. Imagine being able to buy a share in Facebook for example, at a price of say, $100 per share, when the market price for FB stock is $200.

But the only way of get that FB stock on the cheap is buy $100 of government debt first – in effect, to lend the government $100 – before you can convert that loan into FB stock. That act of conversion destroys the government debt, leaving the government deficit $100 smaller. (For the sake of this example, let’s imagine that Facebook has been coerced into this arrangement in exchange for being allowed to operate in this country, or that it’s been granted a monopoly on social media data mining.)

Seems like a pretty good deal, right? Unless the value of that stock, ends up being much less than the value you convert for. So to continue this example, after buying FB stock at a discount through the conversion mechanism above, imagine the price of FB stock has actually been massively overvalued as a result of a speculative frenzy, and as a result collapses well below $200, to say $20. Sucks to be you – but the government is left high and dry.

Both France and the UK did this back in the 18th century, with “debt-for-equity swaps” like the above, by launching the Mississippi and South Sea companies respectively. Both had been granted trading monopolies by their governments, and grand stories of the wealth that they would harvest abroad led to a tremendous bubble in their share price. The governments of both Britain and France fuelled the bubble, as it allowed them to burn their debts into the raging speculative inferno. When the bubble collapsed, it was investors who were left carrying the bag, having done their governments a great service in swallowing their debts pursuit of speculative profit.

Nickolai and I have come up with a thesis of how governments around the world might try this again, but all at the same time, and into just one company. And why not? After all, there’s nobody around from the 1700s to say it’s a bad idea…

The trading monopoly required to excite the most bullish desires of investors will need to be grand. And grand it shall be – indeed, we think the opportunity will be literally out of this world, on a truly lunar scale… but more on that tomorrow.

Until next time,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates