There are some phrases you should always be wary of when you hear them.

“I trust you to do the right thing…”

“I’m not telling you what to do, but…”

“In the end it’s your decision, but…”

“This is not a pyramid scheme…”

“When I’m elected, I will…”

And of course, as readers of this letter will know, Mario Draghi’s notorious “whatever it takes”.

This last addition is a rather unpopular one however. Draghi’s delivery of the line, followed by a dramatic pause, and the kicker “believe me, it will be enough”, said in London on the eve of the 2012 Olympic Games has attracted him an adoring fan club.

The outgoing editor of the Financial Times, Lionel Barber, titled Draghi the FT’s “person of the year” in 2012, mostly due to his use of the phrase, and his admiration of the man has only increased.

President Emmanuel Macron in France was similarly enamoured.

“We make all these communiqués that everyone has forgotten two weeks later. He, on a summer’s day in 2012, he said just a few words, ‘whatever it takes’, and the response was immediate, and the memory is still bright,” he declared to his peers. Macron went on in a speech to address Draghi and say “It’s now up to us, heads of state and government, to carry this ‘whatever it takes’ to measure up to your courage and your clear-sightedness.”

I would suggest that if you hear somebody commit to that particular phrase, it’s worth pondering “what might it take?” before you agree and effectively hand over a blank cheque of your support. For we are slowly discovering the consequences of Draghi’s turn of phrase, and the results are somewhat less splendid than Messrs Macron and Barber would have us believe.

Due to the vagueness of the word “whatever”, and the fact that most central bank actions have a delayed-response time, it’s easy to overlook the consequences of Draghi’s actions.

But now that he’s left, along with Janet Yellen from the Federal Reserve, it’s now becoming ever clearer how far from our expected destination we have come since they took the fork in the road signed “no-interest rates” and “buy the government’s debt until the pain stops”.

Reach for the privates

My ears pricked up last year, when, despite stocks and bonds stumbling strongly from their recent performance, David Rubenstein, the billionaire founder of Carlyle Group, the private equity (PE) firm said business was booming, declaring that “It’s easier to raise money than any time I’ve been in the business over the past 30 years or so.”

Carlyle (coincidentally, Jerome Powell’s alma mater) is a monster of a PE fund with over $200 billion in assets under management. Or at least, that’s how much it values its assets under management – remember, “privates” get to mark their own homework, and they can value their holdings pretty much however they like until they try to sell them to someone else.

Incidentally, the fund IPOed just a couple months before Draghi made his comments – you can find it on the NYSE under ticker $CG. And Draghi’s low rates have funnelled ever more cash into its arms as investors take on ever more risk to meet their obligations.

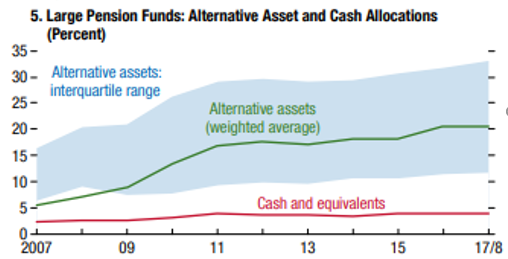

Want to make returns in a zero interest rate world? Gonna need to take more risks, and sacrifice liquidity. Source: IMF

Want to make returns in a zero interest rate world? Gonna need to take more risks, and sacrifice liquidity. Source: IMF

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has estimated that pension funds have doubled their investment in “illiquid assets” (assets which are hard to sell in a rush, like PE, real estate, and venture capital (VC)) over the past ten years. What’s more, it estimates that for 1 in 5 of those funds, illiquid assets amount to more than half of their liquid (easily sellable) assets. They will need to sell those illiquid assets in a pinch, or there’s gonna be… “problems”, of the kind Neil Woodford encountered that ended in his public immolation.

However, as people retire gradually year by year, I’m less worried about all the pension funds attempting to sell their illiquid assets at once. (Unless all their liquid assets fell in value to the point where they sell their illiquid assets to meet the needs of retirees’ retirement redemptions, but that’s a scenario for another time.)

I’m more concerned what illiquid assets they own – and how much they paid for them. For though assets like PE funds are “illiquid”, thanks to low interest rates, the market for them is becoming especially frothy.

Josh Wolfe, a fund manager at VC firm Lux, gave an interview earlier this year for Real Vision, in which he detailed just how easy it has now become for VC firms to raise money, which in turn lead to ever higher valuations for private companies. Want to know where the “unicorns” (tech startups which gain a $1 billion valuation) are being bred and farmed? Look no further than the VC space, which is being continuously juiced by investors (including pensions) starving for returns:

… people are raising [venture capital] funds at ever faster rates before the punchbowl gets taken away. And in some cases, they’re raising the money and saying, look, we’re actually not going to invest this for the next 6 months or a year because we’re still investing out of our last fund. But the FOMO– the Fear Of Missing Out– is still there from limited partners and endowments…

… the problem for the early-stage investors and their limited partners is they were getting these huge markups. And on paper, it looked phenomenal. And then they would go out and raise their next fund and put it into more illiquid companies. But they weren’t necessarily getting liquidity on that billion-dollar company. And you have started to see over the past 3 or 4 years, a lot of these unicorns not go from $1 billion to $800 million. They’ve gone from $1 billion or $2 billion to 0.

What would kick the private markets hard enough to halt all the cash flowing in, and get investors to reconsider a unicorn investing strategy? By his reckoning, an icon must be sacrificed:

… what the catalyst is and when, my bet would be it would be a colossal poster child failure, whether it was from somebody like SoftBank or somebody like Tesla, where everybody hails them as the inventor of the future, you have, in my view, insane valuations, and there is a liquidity crunch at one or both of those companies that has people scratching their heads and saying, wait, what do you mean? How do they not have money? What happened? And then it just becomes this downward spiral…

But until that happens, “privates” are set to absorb ever more investment capital. Indeed, just in September a report titled “The future of defined contribution pensions enabling access to venture capital and growth equity” was published, in which Exchequer secretary to the UK Treasury Simon Clarke wrote:

… the UK’s pension savers ought to be well-positioned to benefit from access to a diverse range of high-quality investment opportunities in saving for retirement… There is an opportunity for DC Schemes to consider how to invest more in such long-term, illiquid assets.

But as we’ll cover tomorrow, for all this risk taking, for all of these ventures into the fringe in search of returns… the pension system still doesn’t have enough cash to make good on its promises. And it will leave a good many people contemplating the true meaning behind “whatever” in “whatever it takes”…

Back tomorrow,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates