What do you make of this thing? Looks like a UFO to me:

Source: Sinot Yacht Architecture & Design

Source: Sinot Yacht Architecture & Design

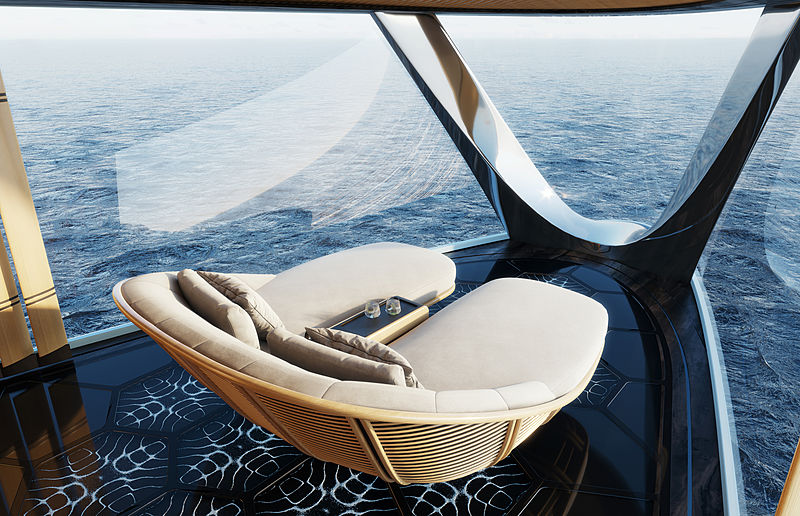

That’s a superyacht concept from a design firm called Sinot. 112m in length, with all the goodies one would expect inside, plus a cosy viewing room inside the prow:

Source: Sinot Yacht Architecture & Design

Source: Sinot Yacht Architecture & Design

This ain’t just any old plutocrat’s toy – it’s stuffed with massive tanks of James Allen’s favourite new energy source: hydrogen.

The whole thing is powered by the stuff, no internal combustion or fossil fuels of any kind. Though I must say the idea of massive hydrogen tanks on board does give me a distinctly Hindenburg vibe.

But moving on to a slightly cheaper way of getter around… You see that tunnel over there?

Believe it or not, that tunnel is 1.5 miles long. You can’t even see light at the end of it when you enter. It’s called Harecastle, the tunnel in Staffordshire I mentioned at the beginning of yesterday’s note.

My brother was parked out there waiting to head through it a couple days back and sent me the photo. It’s a tight fit in more ways than one: only open for three hours a day in the winter months, and only in one direction per day at that.

It’s another “ancient horse’s ass”, of the kind we described yesterday…

But more on that in a second.

Free beer here

Yesterday, I promised a bottle of my favourite Belgian beer would be delivered to the door of a Capital & Conflict reader who can answer a riddle of mine.

Suffice to say, I got a very strong response. And I didn’t even mention that it’s 10% ABV…

But despite the many suggested answers, nobody has guessed it yet. So that bottle will have your name on it if you can figure it out.

If I’m honest, I didn’t expect a winner to show up yesterday, as I didn’t give away too many clues. But I was planning on spreading this piece out as a series anyway, and I don’t mind if you send in another answer.

And as some of your answers were barking up the wrong tree, I’m going to reframe the question. If more than one of you get it right, the beer goes to the first to answer.

Why are oil tankers so slow?

I told you there was a force in the world that almost all investors take for granted in making their assumptions about the future.

This is a force everybody in the West relies on in one way or another; a pillar upon which the entire global economy has grown around.

A vast structure has been built upon it, and by merit of its stability (gathering little press and rarely commented upon), it has effectively been forgotten about, or at the very least taken as a given.

However, its continued stability is by no means certain a given. And the world without it would lack anything like a strong substitute, leading to much higher prices trickling into so many different areas that everybody would notice.

One gentleman suggested inflation was the answer yesterday, but this force is very physical in a nature.

And it has a lot to do with oil. In fact, if I had to boil the riddle down to one sentence it’d be, “How can oil tankers be so big and slow?”

Yesterday, I asked “What do horse asses, a 1.5 mile tunnel in Staffordshire, the Space Shuttle, and the price of oil all have in common?”

Well, we covered the horses’ asses and the Space Shuttle yesterday. Today, you’ll see how the tunnel in “Staffs” shares a similar theme, an “ancient horse’s ass” that has permanently defined the canal network.

And I’ll leave it with you to see if you can find a similar force at play in the oil price: boaz@southbankresearch.com.

Tunnel vision

I only became familiar with this story thanks to a Capital & Conflict reader, who wrote in following my recent letters which touched on narrowboats.

A seasoned veteran of these small craft, I asked them if they could tell me the exact dimensions a narrowboat would need to be if you wanted access to the entire UK canal network (to be as “unplugged” from one location as possible, of course).

The answer they gave was as detailed as it was interesting (emphasis mine):

… the limit to the dimensions of a narrowboat, if you wish to go everywhere on the system is 57’ in length and a width of 6’ 10”. The air draught (from the water level to the top of the boat including chimneys or other things on top) is 7’ 7”.

The story behind those dimensions involves a famous canal engineer, a potter, broken pottery, a 1.5 mile tunnel in Staffordshire, coal, accountants working with pencils and a gain of 4,000% in efficiency.

The canal engineer was James Brindley who started work on a canal tunnel in 1770. A major influence was Josiah Wedgwood who saw the possibilities of canal transport. Up until the advent of the canals Wedgwood was faced with a problem of distributing his wares – one man with a horse on rough roads might be able to transport a ton of finished goods which, correctly packed, might get to their destination with only 25% breakages. One man with one horse and one boat on the water could transport 40 tons with minimal breakages. To a man like Wedgwood this hardly needed thinking about.

Just to the North of Stoke on Trent is Harecastle Hill. Inside the hill was lots of coal. A canal going into and through the hill would enable coal to be floated out on barges, just like a little further North on the Bridgewater canal. It would also enable Wedgwood to send his goods North to Manchester, Leeds, Liverpool and beyond.

So, in the 1760’s, about the time we were being kicked out of America, a proposal was made to dig a tunnel through Harecastle Hill. The original proposal was for a tunnel some 13’+ wide, a height of about 10’ and a length of over 1.5 miles. This was the first time a tunnel of this length had ever been proposed and was truly on the leading edge of technological ability at the time. Whatever the proposed cost was (and I’m sure that the information is available somewhere) it was a massive sum of money for the time.

Then the accountants moved in. Paper and pencil (or Quill and Ink) soon showed if they halved the width of the tunnel and reduced the height then the construction costs would be one quarter of the original figure – a significant saving on a wildly ambitious project. Of course, with the benefit of hindsight…

Thus, at a stroke, the dimensions of Narrowboats or indeed, any boat that wished to be able to travel the full length of the Trent and Mersey canal was fixed for evermore…

Just like in yesterday’s note, I wonder how things would have been in different if the accountants hadn’t moved in, or just not cut the project down as much as they did.

A much broader tunnel, paving the way for a much broader canal (at least in the surrounding area) would have allowed much more coal – energy – to be passed through England. And the more available the energy, the easier economic growth would have arrived. Even more so when you consider the goods that could have been transported down the canal as well.

Entirely new towns could have sprung up alongside it, leading to the creation of families who wouldn’t have got together otherwise. Who knows what their children might have gone on to do and accomplish? And all the other innumerable ways in which history could have changed, had the accountant’s ink been drawn upon the page just a little differently…

But that tunnel is what it is: an “ancient horse’s ass”, which has gone on to shape the world as we know it. I’ll leave you at that for today, and with a more flattering image of the canal than the one I started with.

Until tomorrow,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates