Less than 5% of all bonds yield more than 5%.

Pension funds need 7% to break even, assuming they are funded (most aren’t).

Thus, almost all Pension Funds are fighting an impossible battle to meet future obligations.

They Broke The Entire System.

– David Levine, investment manager

The lengths investors will go for yield in a market environment barren of it is a source of endless fascination here at Capital & Conflict.

We’ve seen investors starving for interest payments get into all manner of risky ventures in this letter. As those who read Walking the plank with John Denver will be familiar (14 August 2018), buying the rights to music royalties… leasing second-hand commercial aircraft… making bridge loans to fast-food franchises… there isn’t much that’s off limits any more.

But for all the income-generating strategies we’ve seen, including financing the Chinese Communist Party’s naval expansion in the South China Sea (Poseidon the profiteer – 14 January 2019)… shorting terrorism for 5.9% per annum marks a new level.

It’ll be a longer note today, but please bear with me.

A quick recap: rabid for risk

Long-time readers will be familiar with the “reach for yield” process brought about by central banks. In trying to create the “wealth effect”, they create money and buy government bonds with it. This increases the price of said bonds, which reduces the total income investors receive from them (their interest payments, known as “coupons”, are fixed).

Investors that require income in order to meet their liabilities, like pension funds, must thus search higher yielding assets, which are more risky. This “reach” then increases the price of those assets, which in turn reduces their yields also, and the cycle repeats.

Squeezed of any meaningful return in “safe” government bonds, they piled into “safe” corporate bonds. Squeezed of any meaningful returns in safe corporate bonds, they piled into junk bonds. Squeezed of returns in junk bonds they piled into dividend-paying stocks, and so on into ever more risky assets.

It’s this kind of dynamic which has lead to booms and bubbles in alternative assets – art, classic cars and cryptocurrencies – while pension annuities pay peanuts compared to what they used to.

It’s also the dynamic that has fuelled the rise of ever more exotic and esoteric assets, such as “catastrophe bonds”, or “cat bonds”. These are a type of “insurance-linked security”, or ILS, which allow insurance providers to get catastrophe risk off their books by selling the insurance premiums on to investors.

Trading typhoons, tornadoes and terrorism

Cat bonds are constructed by insurance providers who first sell a load of insurance policies against catastrophes: hurricanes, typhoons, earthquakes, etc. All of the income streams (the premium payments) from those insurance policies are then packaged together, and sold as a bond to investors.

If no catastrophe occurs, then when the bond matures (when all the insurance policies expire), then the investors get a payout, on top of all the interest payments they’ve earned. If enough catastrophes do occur, then the investors don’t, and the money raised by selling the bond to them is used to pay off the people who bought catastrophe insurance in the first place.

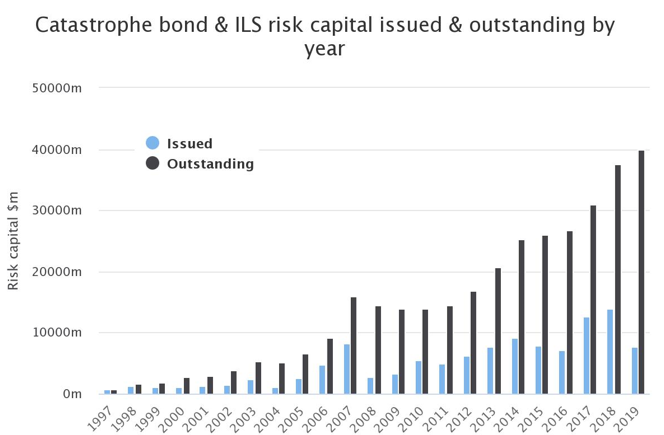

In effect, the investors who buy the bonds become reinsurers, taking the risk of a claim from the company which sells the insurance. And business has been booming:

Chart courtesy of Artemis.bm, a terrific source of data on these niche assets

Chart courtesy of Artemis.bm, a terrific source of data on these niche assets

$7.7 billion worth of cat bonds were issued this year, with a record $40 billion worth now outstanding. Demand is strong, and with junk bonds in Europe now yielding negative, it’s easy to see why – these are some of the few bonds left in the world that still yield above 5%.

Such is the demand for these bonds that the catastrophes covered are now no longer just weather related either. The first ever cat bond created solely from terrorism insurance was issued earlier this year. No acts of terrorism trigger a claim over three years? Bondholders will get their principal plus 5.9% yield out of it.

In a quote that sums up the ever more expansive financialisation of the world, the insurance provider who led the creation of the bond said this to christen the occasion:

“We have been working towards this placement for several years and are excited to bring an entirely new source of capital to the terrorism risk market for the first time. It diversifies the funding of our retrocession programme, complementing the capital of traditional reinsurers to spread terrorism risk even more broadly.”

There’s even the rather macabre Ebola bonds created by the World Bank to insure some areas like the Congo from the virus. From Bloomberg:

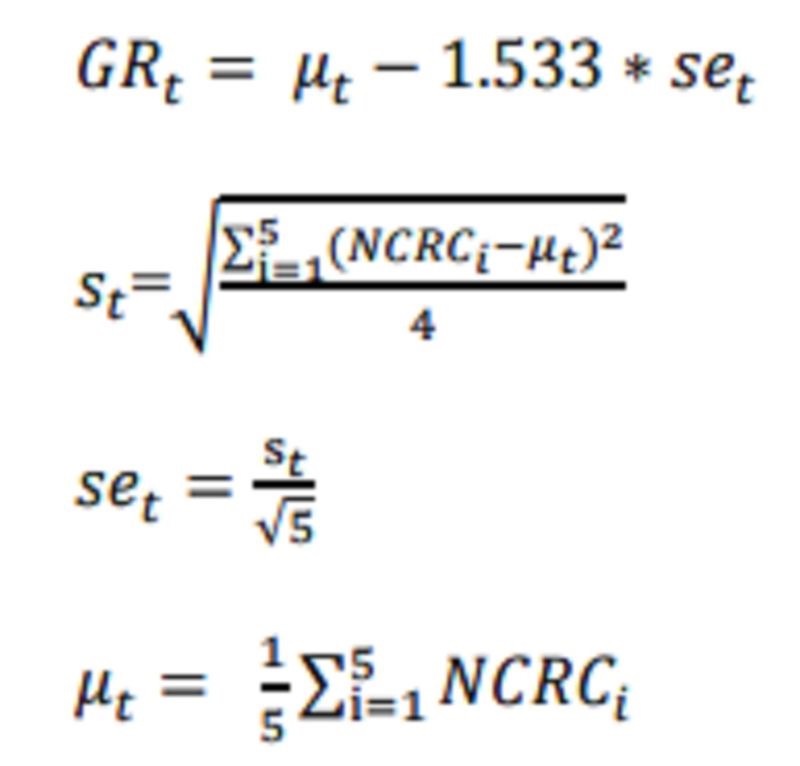

… a $95 million tranche insuring against an Ebola virus outbreak pays investors more than $1 million each month. For the funds to flow to Congo, the disease must cause at least 20 deaths in at least one other country within a specified time window. Deaths must also increase at a minimum rate during this period, shown by a formula that looks like this:

While Ebola continues to spread, just three infections have been confirmed in a neighboring country, all traced back to Congo. The example suggests that the bond’s conditions make it unlikely that the insurance funds would become available early, when they would do the most good, said Andrew Farlow, an economist at the University of Oxford who studies pandemics.

It should be noted that it wasn’t the Congo who paid for the insurance which in turn paid the yield on the bonds – that was Japan and Germany as an act of charity. Those bonds yielded 11.5%, a ridiculously far cry from most other income bearing assets.

However, there’s a reason in this world of low yields that such bonds can still be high yield – Ebola tier levels of risk. A bad year of wildfires, floods, and the arrival of Hurricane Dorian has led to the complacent investor getting “slaughtered”. From the Financial Times:

Some ILS investors are spooked after having been hurt worse than others. Luca Albertini, chief executive of London-based Leadenhall Capital Partners, says: “The private wealth, even when advised by banks, always ignores the health warnings. These people, such as family offices or the multifamily offices, have been slaughtered.”

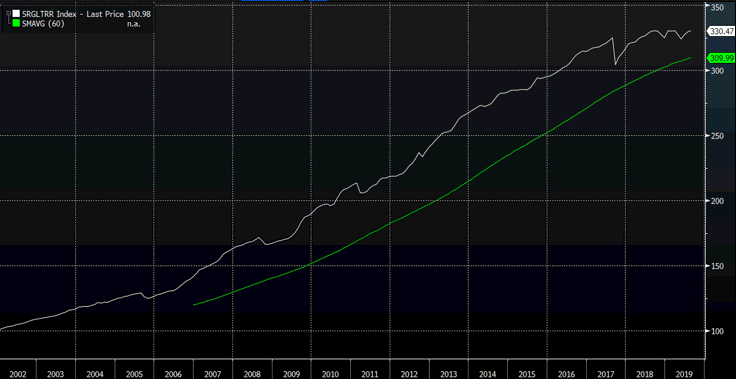

However, if you zoom out and look at a total return chart of the cat bond sector, things are still looking rosy:

Total return of the Swiss Re Global Cat Bond Performance Index

Total return of the Swiss Re Global Cat Bond Performance Index

Source: Bloomberg

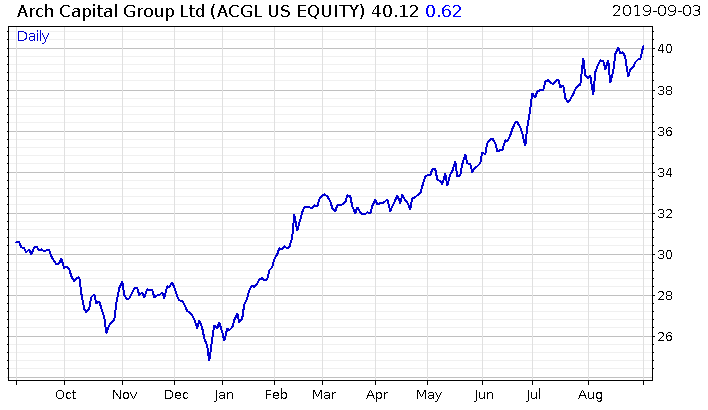

And the companies who create such products are doing very well for themselves. This is Arch Capital ($ACGL), who has created almost $4 billion of insurance-linked securities, including cat bonds:

But cheap insurance distorts risk

Now, I’ve no problem with allowing insurance providers to selling their risk to private investors searching for an income stream. But one has to wonder what the effect of investors reaching for yield in this market will be.

The low interest rates of the 2000s saw banks and investors reaching for yield in the insurance market, just as they do today. Back then, they turned to selling insurance on people making their mortgage payments (specifically, selling credit default swaps on mortgage-backed securities) to earn the extra income that was so hard to find in the bond market.

There was so much selling of this insurance that the dynamic became reflexive, ultimately making it easier for people who probably shouldn’t have been buying homes to getting one (or several) with sub-prime mortgages. This was because the insurance was so cheap (due to such high supply) that the companies originating the mortgages could afford to hedge their risks much more affordably.

Investor demand for the income streams from the insurance created the incentive to aggressively sell that insurance. Similarly to the cat bond today, the insurance itself ended up being packaged into a bond in order to better appeal to bond investors.

As those of you familiar with the story will know, the market for this insurance ended up becoming ground zero in the financial crisis, and those who’d sold the insurance ended up getting nuked.

Before, it was buying a house you couldn’t afford at higher rates… in the future will it be underestimating catastrophes?

If central banks weren’t so aggressively easing policy and keeping interest rates low… would investors be willing to effectively short terrorism for 5.9%? Would the market for catastrophe bonds be so large?

As interest rates go lower, and bond yields continue to plumb lows until that day dismissed as insane, and investors continue to create ever more exotic and risky strategies for extracting income through financial engineering, cat bonds will no doubt become ever more widely issued and bought.

With this in mind, investors portfolios will become ever more exposed to extreme weather events. But their demand for cat bonds will make the cost of catastrophe insurance itself cheaper. In the extreme, this will make life easier for those wanting to operate in areas prone to all the various catastrophes and needing insurance to cover their risk.

The risk of catastrophe itself may end up mispriced as investors are lured into the structure of the insurance market searching for returns that are ever harder to find.

We generally see the moral hazard created by central banks limited to within the financial markets, but this mechanism, in time, has the capacity to effect risk taking in the real-world life.

Readers will no doubt be familiar with the clichéd metaphor used to describe the long-term consequences of seemingly trivial things, in which the flapping of a butterfly’s wings ends up causing a typhoon on the other side of a planet.

Wouldn’t it be ironic, if it was a typhoon in a remote area of the world that brought about the next financial crisis?

All the best,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates