“Everybody would like a little more inflation…”

– Christine Lagarde

We dwelt yesterday on the divisions that have emerged between the millennial and boomer generations.

The rifts that have emerged, especially since the credit crisis, have mostly been contained to opinion pieces in the press. But with the millennial generation soon to command almost a third of votes, it’s only a matter of time before some politico successfully builds a career fighting for wealth redistribution “intergenerational fairness”.

A force which may square the circle of the ageing wealthy boomer and the young broke millennial, is that of high inflation. This may be brought about deliberately (Machiavellian), or indirectly, as the preservation of their elders’ retirement benefits gives way to… other priorities, of the kind we’ll delve into later.

High inflation not only damages retirees’ savings in the bank, but their investments too – the US stockmarket for example, historically performs poorly when inflation is above 4%. Millennials meanwhile, with their prime earning years still a way away, would be more sheltered. They have much more flexibility of income and can achieve salaries that scale in line with the rate of inflation, and would be able to purchase the investment assets on the cheap.

Today’s letter will concern under what guise such inflation could be created. Or to be more blunt, why – as you’ll see a certain stuffed tiger put it – “I think your mom’s going to be bothered.”

Central bankers step on the gas until the speedo works

One route to inflation is for central banks to adopt a nominal GDP target. In short, this means central bankers will “step on the gas” at the printing presses for as long as it takes, regardless of how high inflation goes, until economic activity reaches an arbitrary level they deem important. In theory, all of this activity could be a product of inflation, and they would still be meeting their target.

The adoption of such a target has been discussed in ivory towers for years, and with central bankers looking for fresh strategies, this form of financial repression may well be adopted in future. What the adoption of such a strategy would mean, was summed up well by financial historian Russell Napier:

Many who have read [a previous note on financial repression] believe that it represents ‘the end of the world’. This, of course, is silly for financial repression represents no such thing. It merely represents the end of our world; the world where savers expect real returns on their capital. A move to nominal GDP targeting is simply a recognition that there are now more important goals than allowing such returns.

It recognises the need to reduce global record high debt-to-GDP ratios. It recognises the need to redistribute wealth from savers to earners. It recognises the need to redistribute wealth from old to young. It recognises the need to redistribute wealth. Whether you agree with those ‘needs’ is not relevant, as a move to nominal GDP targeting means that these new goals are now the new normal.

But nominal GDP targeting is only one of the many routes to inflation – and believe it or not, compared to a radical new approach that risen swiftly from the fringes in recent years, it’s positively benign…

The new financial acronym on the block

Before I go any further, there’s a line I want you to remember, a phrase I want you to be able to recognise.

This is an idea, which if successfully planted in the public consciousness will radically change not only the investing environment that has existed for the last several decades, but so much more on top.

If you see a competent political operator start selling this to the public, you better start preparing for the return of high inflation:

Anything that is technically feasible is financially affordable.

That’s it. That is Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT, in a nutshell. You’re going to hear more and more about it in the future – especially from politicians trying to sell it to you. For if they can get you on board with it, the sky is the limit for their pet projects. That’s a line from Stephanie Kelton by the way, an economist and promoter of MMT – more on her tomorrow.

War economies are MMT economies

Edward III borrowed vast sums from Italian banks to finance his campaign. When he defaulted on those loans, the Italian banks were ruined. But Edward was fine, thank you very much. And within a hundred years or so, Edward’s successors were getting loans from other Italian banks. That’s the core logic of Modern Monetary Theory. A sovereign’s gotta do what a sovereign’s gotta do, and private capital just has to deal with it.

– Ben Hunt, in Epsilon Theory

MMTers claim that the only constraint to government spending (governments which can borrow in their own currency, that is) are real resources – the actual capacity within the economy for activity.

The government, MMTers argue, creates money by spending it first, and then taxes and borrows it back, both of which it doesn’t really have to do – the government can run perpetual deficits ad infinitum. Inflation only arises when the government spends more than the economy can actually produce, and should be contained using taxation, not higher interest rates.

Newly converted MMTer Kevin Muir, a trader and fund manager, argues that government spending in wars shows that this is the case:

Why is there always money for war?

Do you think that after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor the United States government went to the bond market to borrow money to build back their navy? And do you think that if the bond market had not provided those funds the United States government would have said, “sorry – we really want to enter the war, but we will have to wait until market conditions allow us to finance our deficit spending.”

Of course you don’t. The government spent first and did not worry about borrowing.

Though the US government did issue war bonds to finance the war effort, MMTers contend that this was not to actually raise money, but to prevent individuals from buying goods that were needed for the war, and so offered them an interest bearing asset to buy instead. The government was borrowing from its citizens and large investors, not because it needed the money, but to influence the private sector’s behaviour.

In short: MMT is the skeleton key to any government boondoggle. This idea gets adopted by those in charge, you can wave farewell to the decades of low inflation that have been so kind to equity prices, and the purchasing power of your bank account. Or, put another way, you can say hello to a destructive rebalancing of wealth from old to young.

The excuse narrative used to seize control of the printing press is already been developed and distributed – a topic we’ll explore in tomorrow’s letter.

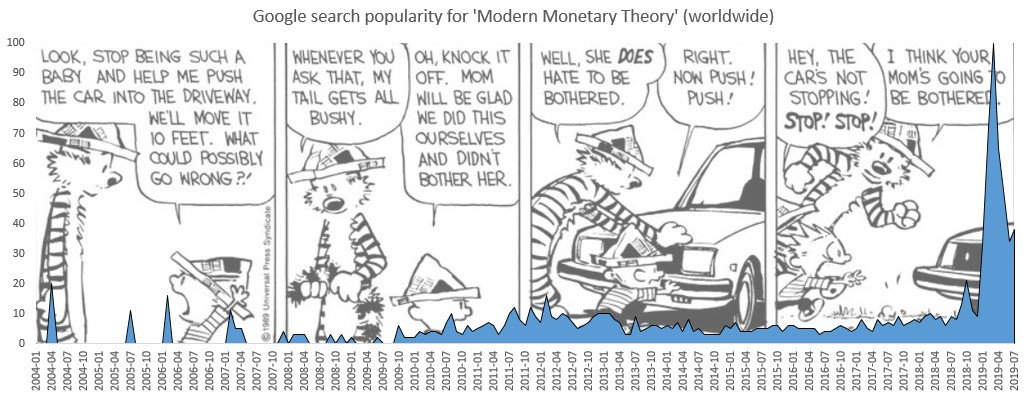

But I’ve a chart to show you before I leave you for today. A couple weeks back in this letter (“Cool (and political)!” – 15/07/2019), we mentioned how the millennial generation had been raised in a historically rare period of low inflation (rare in an environment without a gold standard, at least). However, their political ambition to make money “cool and political” threatens to bring inflation back significantly, in a way neatly summed up by a certain Calvin and Hobbes comic strip.

Think MMT is too far out of an idea to ever be implemented? This idea has momentum:

Source: Google Trends

Source: Google Trends

(Click to enlarge)

A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term – a value of 50 means that the term is half as popular, etc.

Popularity never hit zero after the financial crisis. Hmmm…

More to come,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Capital & Conflict

Category: Market updates