If you were a government looking to default on some debts and didn’t want to ruffle many feathers, who would you decide to default on?

Which lender would be the most politically palatable victim? And which would damage your credit score the least? Markets have a long memory after all, and you’ll probably want to borrow from them again in the future. Burning as few creditors as possible in a default is paramount, if you want to drink from the debt trough.

In the context of Italy, I think the answer they might arrive at is the European Central Bank (ECB). The ECB has a limitless chequebook after all (providing whatever it’s buying is in euros) and can be portrayed to the Italian public as the reason for their economic stagnation. This is true to some extent as the inability of Italy or the market to devalue Italy’s currency prevents it from regaining competitiveness.

And it wouldn’t be defaulting on any private investors, which would do less damage to Italy’s credit score. Of course, the repercussions of such a default would be huge – for financial markets, for Europe… and even for the solvency of the ECB. Nobody really considers the insolvency risk of a central bank thanks to their ability to print money, but in certain scenarios this can occur. More on that later in the week.

A boatload of bonds to push forward

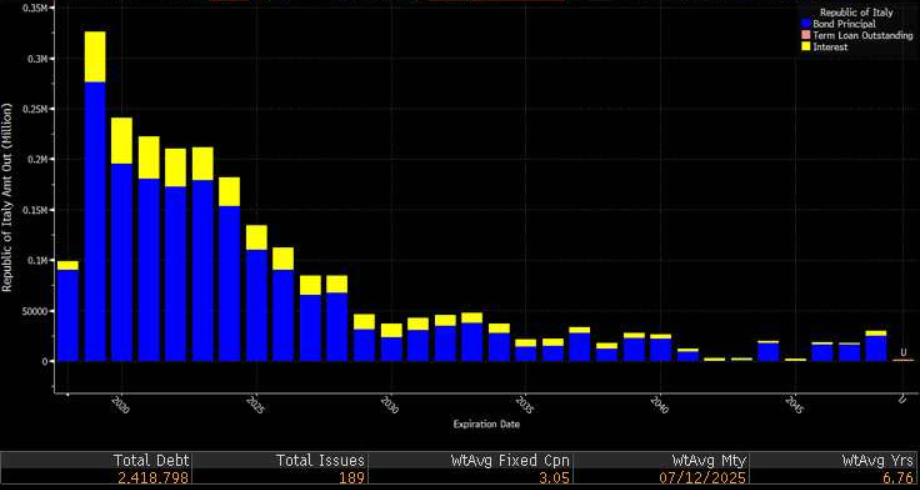

To put the Italian debt situation in perspective, take a look at this chart, courtesy of Bloomberg. This is the “debt maturity profile” of Italian government debt, displaying how much is due per year, with interest in yellow and the principal in blue.

The short bar on the left is the amount of debt Italy must pay back by the end of the year. The largest bar (right next to it) is the debt Italy must pay in 2019. To help with all the zeroes, the debt here is displayed in millions of euros – alas, Italy’s debt is not €2.4 million as the figure bottom-left might suggest, but €2.4 trillion.

With much of that due next year, Italy will do what most governments do, which is roll it over – borrow more to pay off the debt due and push the problem into the future. On top of that, it’s committed to running higher deficits, which means even more borrowing so it can fight austerity, “abolish poverty”, etc.

However, when it goes to the market to borrow more next year, the market will demand a much higher rate of interest than the Italian treasury has been used to – as illustrated by Italy’s current ten-year cost of borrowing:

This rollover will be a painful one – provided there aren’t any radical changes first.

The debt will continue to spiral until there is some form of catharsis. This could be a default on government bonds as previously mentioned, or an explosion in Italian economic growth, which – while it’s stuck in the euro – is hard to imagine.

In the meantime, Europe is becoming radioactive for bonds in general, let alone Italian government ones. A Dutch bank has become the fifth borrower to withdraw from issuing bonds in Europe’s primary bond market in little over a week, citing “market conditions” as unfavourable.

A change in the tide is underway…

Until tomorrow,

Boaz Shoshan

Editor, Southbank Investment Research

Category: Economics