At the last minute, Donald Trump rescued his allies from his own trade war. He extended the exemption from steel and aluminium tariffs for another 30 days. But it wasn’t enough to prevent US steel stocks from sliding about 5%.

The American beer industry’s lobbyists are grumpy too. The aluminum cans they use are made of aluminium. And Trump’s tariffs threaten to raise their costs even more than sanctions on Russia already have. Hundreds of millions of dollars are at stake.

But as we looked into yesterday, the threat of tariffs is working. At least as far as Trump is concerned.

Australia, Argentina and Brazil are all lined up to receive permanent exemptions from the tariffs in exchange for concessions and renegotiating trade agreements. The trade delegation to China is on the way. Only the EU is a holdout.

But it’s all a distraction from the bigger issue. The worm is turning.

The end of global synchronised growth

The world’s upcycle is over. Enough indicators are flashing red. It’s a culmination of the many things you’ve been reading about in Capital & Conflict for months.

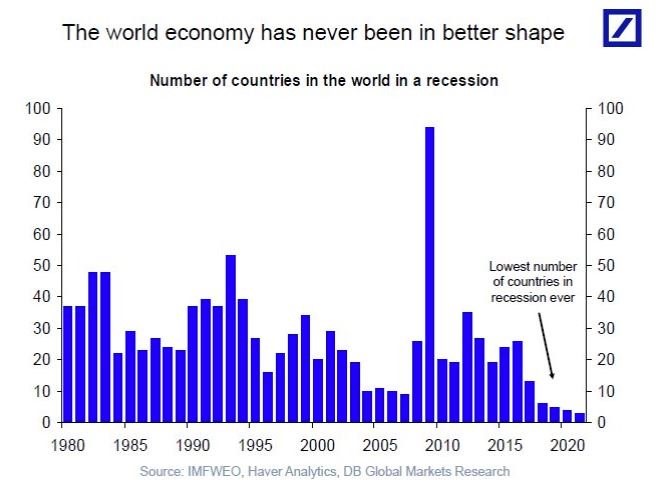

The number of countries around the world in recession is at a record low. The last time this level of synchronised growth took place, it was followed by 2008.

Source: TheoTrade

Source: TheoTrade

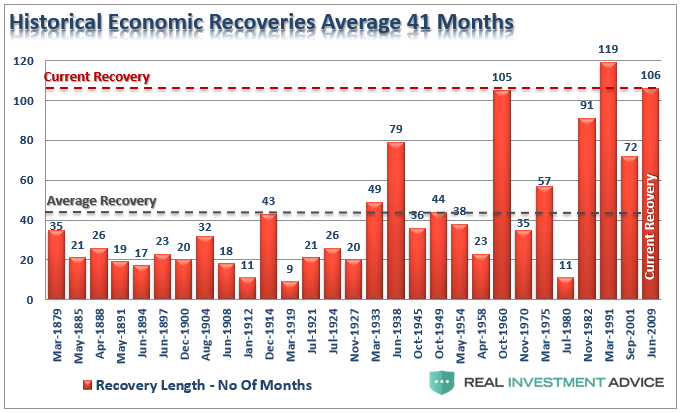

The length of the US’ economic expansion is also at record levels. Only the 1990s delivered a longer period of continuous growth without a recession. The Americans have almost reached triple the length of the average recovery.

The concern is that a longer recovery allows a bigger build-up of malinvestments. When the recession comes, it will expose a far larger set of problems than usual.

It all looks like a peak to me.

GDP growth is already slowing in Europe. The UK economy grew a paltry 0.1% last quarter. The euro area lost a third of its growth rate from the fourth quarter of 2017.

In Canada and Australia, the housing bubbles look to be bursting at last. Mainstream analysts are forecasting a 5% drop in house prices in Australia, something considered impossible only years ago.

Global M&A reached a record $1.2 trillion in the first quarter of 2018. That’s well ahead of the peak in 2007.

The list of peaks, turning points and warnings goes on. It’s bad news all round. A global recession is coming.

The war chest is full of debt

What about the ability of governments to respond effectively to the new recession threat?

Government budgets have hardly recovered in this recovery. Debt to GDP is expected to fall in some places thanks to plenty of economic growth, which won’t actually happen. When it doesn’t, and the debt trajectory is adjusted, there’ll be new fiscal crises. The European sovereign debt crisis is due for a comeback.

It’s not just government debt. Personal debt is a bigger problem than in 2008 too.

Put together, government and private debts were at 225% of global GDP in 2016 according to the International Monetary Fund’s latest figures.

Interest rates are still at ridiculously low levels. They can’t be cut much. Quantitative easing (QE) continues around much of the world, despite the supposed recovery.

If the coming financial crisis is debt related – a near certainty – then a spike in interest rates will easily crush the victim. And central banks and governments are maxed out. They can’t respond.

The only question is, who is the weakest link? Who will crack first?

Here’s my pick. I’m on the record.

This year, the biggest bankruptcy in history will blow up the financial world. And a global recession is just what’ll trigger the coming debacle.

Is Italy the weakest link?

If a global recession is enough to spark a financial crisis, you have to find the weakest link to discover what will snap first. One candidate is an entire country. And it’ll make Greece look boring.

In an online video posted on Facebook, the leader of Italy’s biggest political party argued for new elections. Two months of negotiations haven’t delivered a government.

The wacky left-wing Five Star Movement is the biggest single party. The two right-wing movements are bigger if they stick together. But the formerly mainstream centre left has enough votes to hamstring both.

Since the 4 March elections, negotiations every which way took place. And a few local elections happened too. The consensus is that the former mainstream party is losing ground, while the right-wingers gain ground fast.

New elections might happen in June, but more likely in September.

I’ve never seen anything wrong with a hung parliament. If people vote for a quagmire, why not keep it that way until the next election is due? Belgium did fine in its 589 days without government in 2010. People must have come close to realising they don’t need politicians to constantly change laws.

But that definitely is not the case in Italy. The country is headed for an epic reckoning. On every possible angle, it’s a desperate mess.

Government debt is out of control. Debt to GDP is second only to Japan. Economists, especially German ones, are convinced the country’s government is surviving on the goodwill of the European Central Bank (ECB). And by goodwill, I mean deficit financing through monetisation.

Italy’s dodgy loans are about the size of the US’ sub-prime problem.

The reckoning might already have begun. In the wake of the Five Star Movement’s call for new elections, the Italian stockmarket fell while others in Europe rose. The yield on Italian bonds shifted up too.

The problem here isn’t the immediate problem. Plenty of countries around the world have lots of government debt, lots of bad private debt, and a political standoff.

What makes Italy different is that it has the weakest hand, combined with being inside the eurozone.

What to watch

The political situation in Italy is the key. Financial markets are merely applying pressure.

Italy’s new dominant political parties used to favour abandoning the euro to some extent. Some advocated debt defaults too. These days, with more slick leaders in charge, the new plan is to renegotiate with the EU. The Italians want to run bigger government deficits than allowed, for example.

Running bigger deficits when debt is your problem might seem like a bad idea. But it’s always worked in Italy. That’s why they have so much debt. And it’s why the ECB is buying so much Italian debt.

But the ECB has legal limits. And the Italians aren’t trashing their own currency, but Europe’s. The exchange rate is applying more pain instead of alleviating it like the lira used to. The euro keeps rising in the face of Italy’s economic crisis.

Unlike Japan with the yen, Italy can’t print euros forever. The limit will be the decisive feature that triggers Italy’s crisis.

It all looks very much like a powder keg. And the coming global recession has lit the fuse.

To find out just what’s going to happen, and what to do about it, click here.

Until next time,

Nick Hubble

Capital & Conflict

Related Articles:

- Opt out of the blunder from Down Under

- The pension panic is coming

- There will be a little pain in the stockmarket

Category: The End of Europe